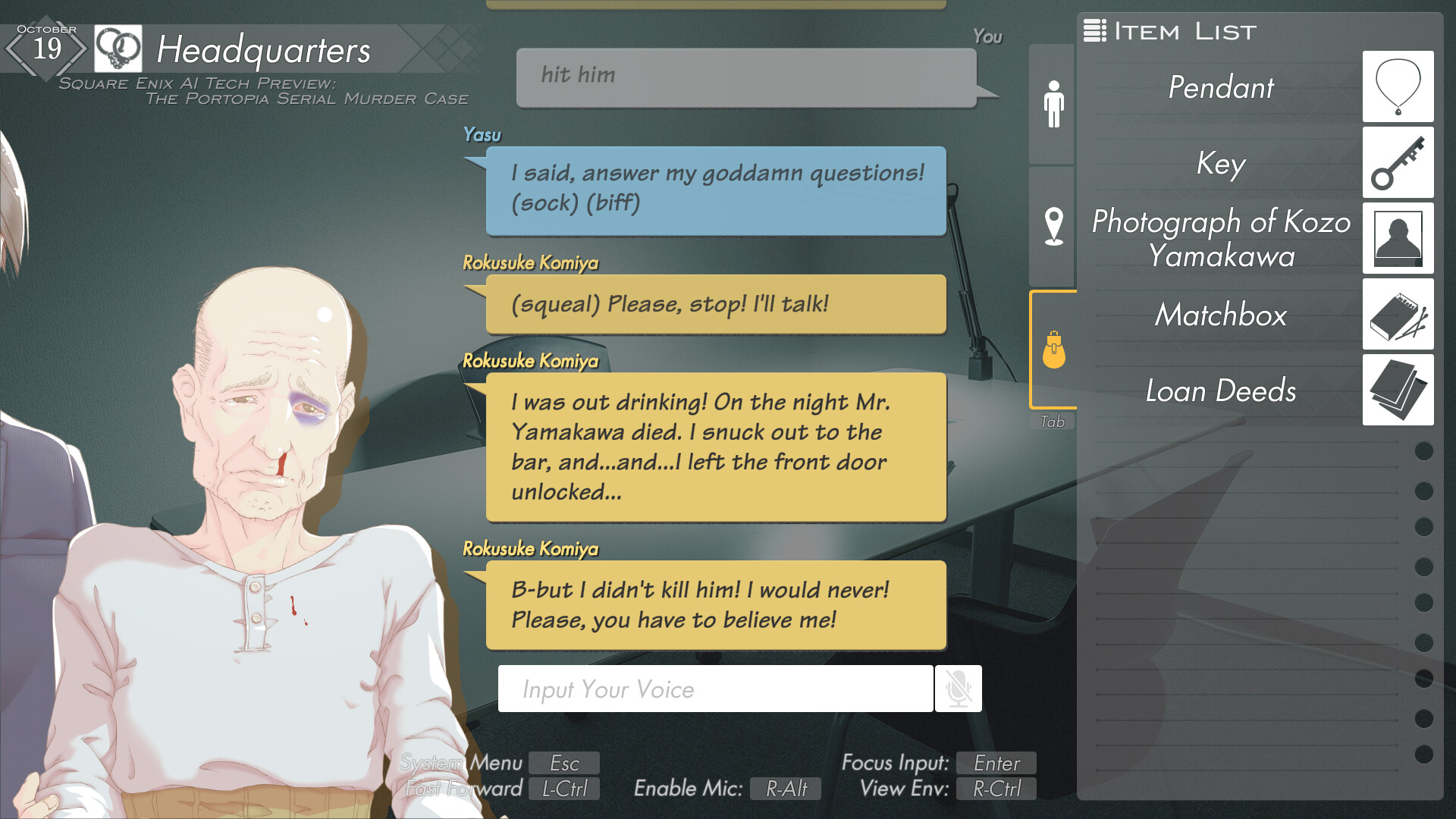

On Monday, Square Enix released an elegantly named tech demo, designed to make a case for the emerging uses of AI in games: SQUARE ENIX AI Tech Preview: The Portopia Serial Murder Case. The demo is built around a modern port of The Portopia Serial Murder Case, a highly influential Japanese adventure game, onto which they have added a Natural Language Processor.

Natural Language Processors derive meaning from, and then generate, text. ChatGPT, for example, uses an NLP, albeit a much, much more complex one than is on display in Square Enix’s tech demo. NLPs can be broken into two distinct parts: Natural Language Understanding and Natural Language Generation. Natural Language Understanding allows computers to derive information from a text, and Natural Language Generation allows them to construct new sentences based on the texts they have been trained on, and a prompt.

Videos by VICE

The Portopia Serial Murder Case, originally released in 1983, is one of the most influential Japanese video games of the 1980s. While simple by modern standards, the game’s open-endedness, narrative focus, and use of a text parser, were a significant departure from design standards of the time. It all but sparked the visual novel genre, and led to dozens of copycat detective games for the Famicom, two of which were lovingly remastered for the Switch. Despite its influence, The Portopia Serial Murder Case never received an official English release—at least, not until this NLP-powered tech demo.

The NLP that Square Enix is using appears to be one of its own making. Unlike ChatGPT, which runs on OpenAI’s servers, the NLP used in this version of The Portopia Serial Murder Case appears to be local, which would explain the game’s surprisingly large 10gb file size. This NLP is intended to make the game more open-ended by allowing players to control the game as if they were talking to a person. While Square Enix claims to have built a Natural Language Generator, it has been disabled for this initial demo, because the company could not stop it from generating “unethical replies.”

Public response to the tech demo has been overwhelmingly negative, with only 12 percent of Steam reviews being listed as positive. This makes it one of, if not the most, poorly reviewed games on all of Steam. Complaints run the gamut from the game’s disorienting art style, to its massive resource load, and barely a single review goes by without mentioning the fact that, despite being a tech demo literally built around the technology, this version of The Portopia Serial Murder Case is absolutely terrible at actually understanding what the player wants to do.

When I played the game, its NLP struggled to distinguish between the phrases “Go to study” and “Go to the study,” but is inconsistent about which of these is the correct phrasing. This is, somehow, a less efficient control method than the original game’s text parser, which relied exclusively on “Object-verb” commands, with appropriate aliases so the player doesn’t have to say the exact phrase required. Even with plenty of aliases, traditional text parsers struggle to accept player inputs—ideally, this is where the NLP would come in, but, for now, it’s a complete failure in practice.

The NLP takes your natural language and attempts to translate it into Object-Verb format regardless of whether or not translation is necessary for a given action. And not only does this lead to miscommunications between the player, NLP, and text parser, but also takes a massive toll on your computer’s performance. NLPs are frequently resource intensive programs, which is why the vast majority of them run on the cloud, relying on massive servers to do the actual work before sending a result back out to users. This is not the case for The Portopia Serial Murder Case, which ground my computer to a halt.

These performance issues became particularly problematic when attempting to use the game’s Speech-to-Text system, which relies on your GPU and requires an astounding 5 gb of VRAM to achieve “medium quality.” When I attempted to turn this system on, the game instantly froze, and I was unable to do anything on my computer until I force quit the executable.

If this version of The Portopia Serial Murder Case was intended to demonstrate a newly emerging technology to audiences and developers alike, then it has done so quite elegantly—immediately revealing to anyone who spends more than five minutes with the game how empty the promise of AI in games currently is.

This tech demo is particularly strange in context. You do not need to prove the utility of NLPs in games, because that work has already been done. AI Dungeon, a game entirely built around NLP technology, has been available since 2019—and it is capable of so much more than what is on display in The Portopia Serial Murder Experiment. It, unlike Portopia, is capable of Natural Language Generation. If you tell the game “I walk into the room and stab the King,” it will engage in free-form, improvisational storytelling with the player. In recent updates, the game has included basic AI image generation, in addition to its NLP model. Similarly, there’s very little reason for a program like this to run locally on a player’s device. There are also many off-the-shelf NLP options that would likely be better at parsing a player’s input than the AI that Square has built here.

In addition to this basic model, players and developers have created settings upon which the game is trained. These provide world details, tones of writing, and rules within which the AI will operate. They are, arguably, one of the best parts of the game. Stepping into a new world, even one that is lightly traced by a human hand, is a novel experience—at least, until the AI model forgets what has happened so far in the story and everything falls apart, revealing the hollow core underneath.

Sometimes, AI Dungeon will tell a cute or surprising story. Most of the time, it will be extremely generic or borderline nonsensical—because that is what these models are able to produce without strong, human guardrails. Even in its best moments, AI Dungeon is a novelty with a bit of potential. It creates an illusion of depth, and Square Enix’s tech demo cannot even manage that. It is a failed magic trick.

The Portopia Serial Murder Case may be a particularly bad, technically messy port of an extremely influential classic, but it is in no way alone in this. The iOS releases of several early Final Fantasy games and the recently released Final Fantasy Pixel Remasters, also made by Square Enix, were widely criticized for their approach to updating the original games’ art. The 2013 iOS releases were cartoonish and blurry, the 2021 pixel remasters were less detailed, with heavy black outlines. In both cases, these remasters were trying to recapture an aesthetic built for CRTs, instead of developing CRT filters which one could apply over the original graphics on modern screens. Given the extreme precarity of archival work, and of maintaining access to older systems and display methods, these versions of the game may eventually supersede the originals in the cultural memory of the video games industry.

This is particularly frustrating in the case of The Portopia Serial Murder Case, a game which was successfully ported to the Famicom—effectively translating the game’s controls to fit newly emerging technology. They have succeeded in this task before. The Famicom version of The Portopia Serial Murder Case relied on a much simpler and much more effective menu system, while still maintaining the same degree of player expression on display in both the original game and this modern, AI fueled port.

The original text parser and modern NLP do not, as some hope, actually increase one’s capacity for expression, they only create the illusion of a world that can react to anything you say. It is this same illusion of a more expressive, but ultimately empty, world that leads to games increasing in fidelity and decreasing in legibility, year after year, begetting remakes of games removed from their context.

The Portopia Serial Murder Case is, like the original Final Fantasy games, an essential part of the medium’s history. And I hope the failure of this tech demo is a lesson. The use of AI in updating the game for modern hardware sets a dangerous precedent, one in which we hand the history of our developing medium over to algorithms and language models, which have proven time and time again to be little more than novelties and particularly competent parrots.