The 27th of January, 2020 is the 75th anniversary of liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Between 1940 and 1945, the Nazis murdered 1.1 million people inside the concentration camp, including nearly 1 million Jews.

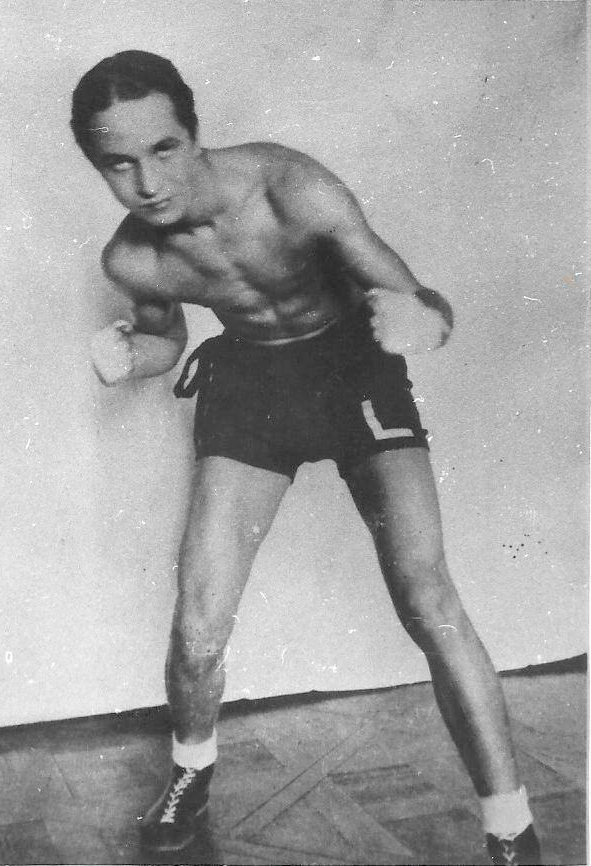

One of the first prisoners taken to the camp was 23-year old Polish boxer, Tadeusz “Teddy” Pietrzykowski. Before the war, Teddy was the bantamweight vice-champion of Poland and a champion of Warsaw. During his incarceration he was forced to fight dozens of matches.

Videos by VICE

Dr Karol Nawrocki is the museum director at the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, Poland. I spoke to Dr Nawrocki, a former boxing champ himself, about Teddy’s life and the brutality of boxing in the concentration camps.

VICE: When did Teddy discover boxing?

Dr Karol Nawrocki: In his teenage years, though we know that back then his sport of choice was football. Teddy left behind notes about his workouts, which tell us how he was developing tactics and technique. His coach was Feliks “Papa” Stamm, who raised whole generations of boxers, both before WWII and after.

And then came the war.

Exactly. On the 8th of September [1939], Pietrzykowski was defending Warsaw – his hometown. He fought in the light artillery regiment. You could say he was not only defending the country, but also his home, his street, his close relatives and people he knew.

After the Polish army surrendered, he was forced to run. He was arrested by the Germans on the Hungaro-Yugoslav border. He was 23 years old. He went to prison in Muszyna, then in Nowy Sącz and Tarnów. After that he was transferred to Auschwitz in the first mass transportation. His camp number was 77.

How did his first boxing match in Auschwitz come about?

He didn’t start boxing right away – in the beginning he was assigned to work in a carpenter’s shop. Being fit helped him survive the hard labour. His first boxing opponent was Walter Dünning – a German prisoner – who, before the war, was a middleweight vice-champion of Germany. This was March, 1941.

Dünning’s fellow inmates suggested, if he liked abusing others, maybe he should try fighting Pietrzykowski. Dünning was 70kg, Pietrzykowski about 40kg. They fought in their working gloves. Dünning stopped the fight when he realised that he was losing, and Pietrzykowski got a loaf of bread and a bar of margarine as a prize. He shared it with other inmates.

How many boxing matches did Pietrzykowski fight in Auschwitz?

We are aware of 40 to 60 boxing matches. He lost only once – to a Dutch Jew, Leu Sanders. Eventually, Pietrzykowski won in a rematch. I’d like to point out that, although we’re now fascinated by the history of boxing in concentration camps, these contests are proof of the sheer barbarity of the people who built and ran those camps. Teddy had to fight other inmates – many of whom were his fellow countrymen – for food scraps. It was his chance for survival. But I like to imagine that those fights were like a hope transfusion in a place without hope. A Pole beating up a German in the Nazi concentration camp, in the face of unspeakable horror.

According to Teddy’s memoirs, he became a member of the resistance movement in Auschwitz.

Yes, he was collaborating with cavalry captain Witold Pilecki, who got into the camp voluntarily under a false name to gain proof of Nazi crimes and organise resistance. In his reports, Pilecki recalled Pietrzykowski as a boxer who shared the food he won with other resistance members.

And Auschwitz wasn’t the only camp where Pietrzykowski boxed.

Correct. On 14th of March, 1943, he was relocated to the Neuengamme camp near Hamburg, where he fought about 20 matches, and then to the Bergen-Belsen camp, where he was eventually liberated by British soldiers.

What happened to Teddy after the liberation?

He joined the Polish 1st Armoured Division under Major General Maczek as a sports coach. Then he returned to Poland and became a PE teacher in Bielsko-Biała. He didn’t pursue a boxing career after the war – he devoted himself to working with youth. In one of the gyms he worked in, he wrote a motivational slogan on the wall for his pupils: “To be, is to be the best.”