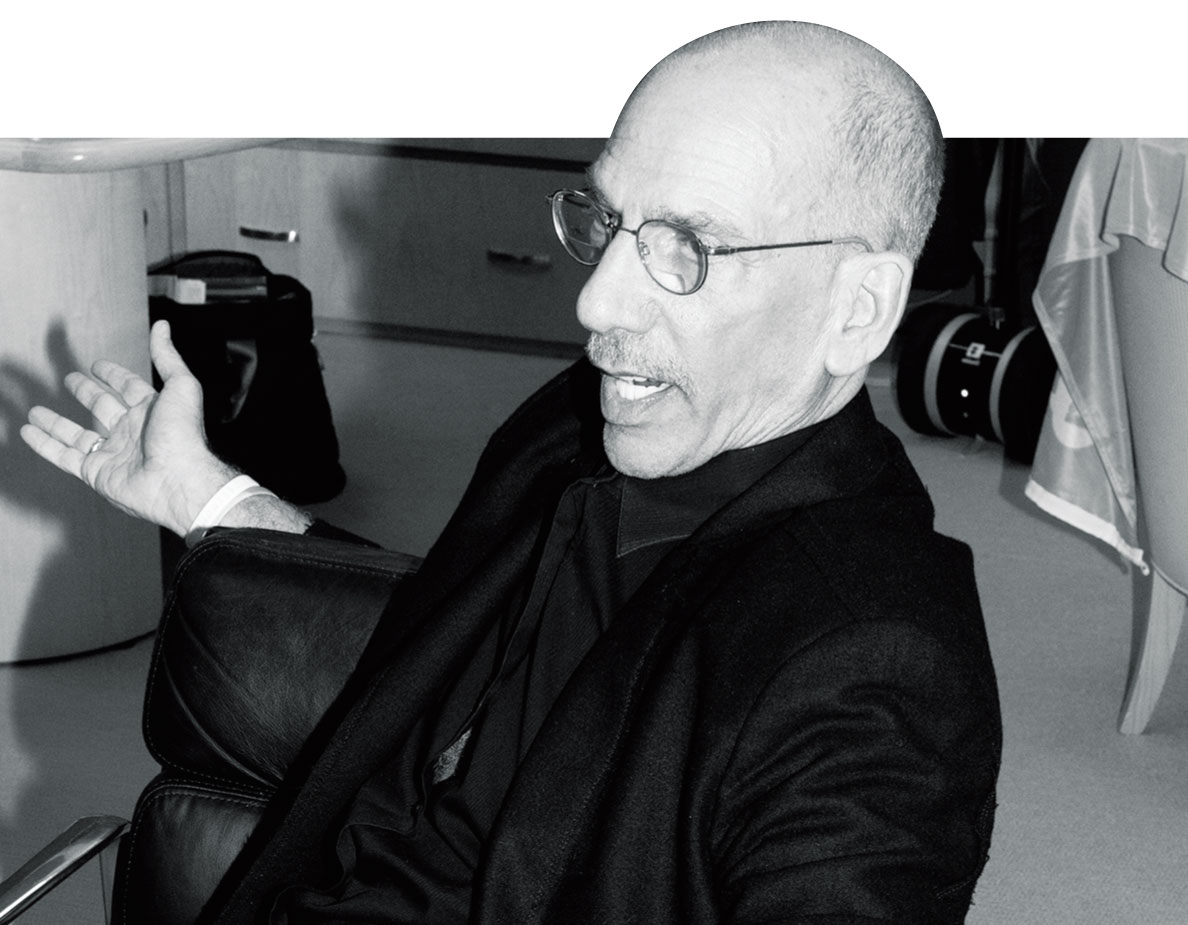

Photos by Sam Clarke

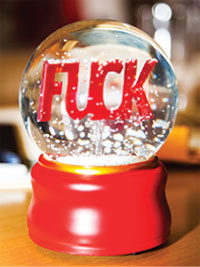

As I walk into Bob Sillerman’s Park Avenue office, there is no question as to what his favorite word is. It’s spelled out inside a snow globe on his desk. It’s represented in mylar FYYFF—Fuck You, You Fucking Fuck—balloons that wave in front of his windows, no doubt visible to the passersby six floors below. “I hate this fuckin’ office,” he says. “We’re moving down to Twentieth and Broadway.”

Still, the abundant F-word isn’t so much a birdie to the denizens of midtown Manhattan as a fuck-you to the American financial system, which has lured Sillerman and his particular brand of business—live-music roll-up conglomerates—back to play in the world’s biggest concert venues and on the stock market.

Videos by VICE

To say Sillerman is brash is to belie his sense of humor (he pokes fun at our young photographer’s age by immediately asking him what year he graduated from high school). To say he is enterprising is to disregard the fun he clearly has doing his job. At 66, Sillerman is a seasoned music executive, having pioneered the model for his current company, SFX, with a previous business of the same name. That company eventually became what is now Live Nation (and, ironically, Sillerman’s archrival).

He is also a cancer survivor and speaks through a tracheotomy, typically concealed by a turtleneck or a high-collared shirt. For our interview he attaches a discreet microphone to his ear, which amplifies his voice through a small speaker he places on the table in front of him (he jokes about how it can also pick up his flatulence). It’s a small reminder of mortality that even a reported billion-dollar fortune can’t alter.

In the past few years, Sillerman has become notorious in the dance-music industry for buying up a string of once-independent rave promoters and affiliated service companies to form the second incarnation of SFX, a NASDAQ-traded company (SFXE) as of October 2013. Through acquisitions of the Amsterdam-based ID&T, New York’s Made Event, Chicago’s React Presents, Disco Donnie Presents, and Beatport (the pioneering digital music store for electronic music), SFX has taken the once-underground culture of raves to Wall Street.

“Some of the growth was incorrect,” Sillerman concedes, alluding to but not naming some SFX purchases that may have been made in haste. “Live events are so energetic and incredible, but it’s an industry where people put on a festival once a year yet everybody listens to music year round. When we acquired Beatport the idea was to create a community 365 days a year. I was interested in protecting the fan experience and not doing what everybody thought I would do, which was corporatize it.”

In business, of course, the fan experience becomes secondary to the stockholder experience. At the one-year mark of SFX’s IPO, the stock price fell from its opening $13 to under $5 (and briefly under $4). The CEO remains unfazed.

“I don’t mean this arrogantly, but this is my tenth public company and the twenty-sixth one I’ve started,” he states flatly. “If people are impatient and they want more [immediate returns], they don’t need to buy the stock. That’s what the sell-off was on this. And that’s fine.

Like other F-word paraphernalia in Bob Sillerman’s office, this snow globe is a fuck-you to the American financial system.

“I have the good fortune of having the capacity to buy stock,” he continues, while acknowledging that because he is already rich from his previous ventures, in his current position his salary is a nominal $1 a year.

The scepter that looms larger than stock prices over all of dance music is the reality of drug-related illnesses and fatalities at events. A month before SFX’s IPO in 2013, Made Event’s Electric Zoo canceled its third day of music after two ravers died from drug-related causes at the New York City festival. In 2014, festivals across North America were beleaguered by similar incidents despite efforts by some in the industry to increase onsite safety measures.

“Let’s not be naive,” Sillerman levels. “Kids are going to do what we all did. They’re going to make decisions, some of which might be bad decisions about alcohol use or drugs. Trying to mandate against that is impossible. You can educate, but most importantly, what you can do is protect kids from their bad decisions.”

At some SFX-owned events, like TomorrowWorld, outside Atlanta, promoters have partnered with DanceSafe, a harm-reduction and drug-health-awareness group, to provide substance-specific information on site in the form of pamphlets and access to public-health professionals who answer questions, though they do not sell or distribute controversial drug-testing kits. To Sillerman, education is smarter than scare tactics, and investments in extensive medical services at SFX festivals (in North America, at least) are an undisputed priority.

“In thinking about my generation where drinking was so vilified, the people who became troubled by alcohol were the ones who had no experience with it,” he says. “I’m not making a moral statement. I want kids to be informed, to make good decisions, but I know they won’t always.”

Sillerman pauses and warns that he will not answer a follow-up about what he is about to say.

“I lost my daughter two years ago at age eighteen. No kid who can be helped or saved is going to suffer on my watch. Period. Full stop.”

He pauses, then refocuses his attention.

“Let’s lighten it up a little bit,” he says, impishly. “How do you dye your hair?”

Zel McCarthy is the Editor-in-Chief of THUMP, the electronic music and culture channel from VICE.

More

From VICE

-

Paul McConnell/Getty Images -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

WWE