It’s a Friday evening before sunset at American Legion Post 801, one of just two bars in the remote desert town of Bombay Beach, California. The bar, the walls of which are covered in dollar bills, is packed wall to wall. The locals, smoking cigarettes and nursing bottles of Bud Light and boozy concoctions in red Solo cups, are huddled around folding tables on the patio watching the parade of outsiders stream in from luxury cars in the dirt-covered parking lot. Some are wearing glittery leotards, top hats, and kimonos, and many have driven some 170 miles southeast from Los Angeles to arrive here on the coast of the Salton Sea, a gradually shrinking body of water so saturated with salt and pesticides from agricultural runoff that scientists have called it an environmental disaster in the making.

A former resort town and a posh celebrity hangout in the 1950s and 60s, Bombay Beach today exists in a state of disrepair. Its visitors—which supported its now defunct marine and tourism industries—have all but vanished along with its jobs. Many homes have been abandoned, and there are no gas stations or grocery stores for miles. The water in the Salton Sea, formed more than 100 years ago by an accidental canal break in the Colorado River, is brown and murky. Its shores are littered with the bones of dead fish and birds—biologists have attributed the die-off partly to parasites in the water—and the air often smells of rotten eggs, the result of high levels of hydrogen sulfide.

Videos by VICE

But for this one weekend in April, the town is hosting the grand opening of an opera house, a drive-in movie theater, a lecture hall, and an art museum—all resurrected from the ruins of decaying foundations. Known as the Bombay Beach Biennale, the event’s wealthy LA-based organizers see it as a way to breathe new life into the down-on-its-luck town, if only temporarily.

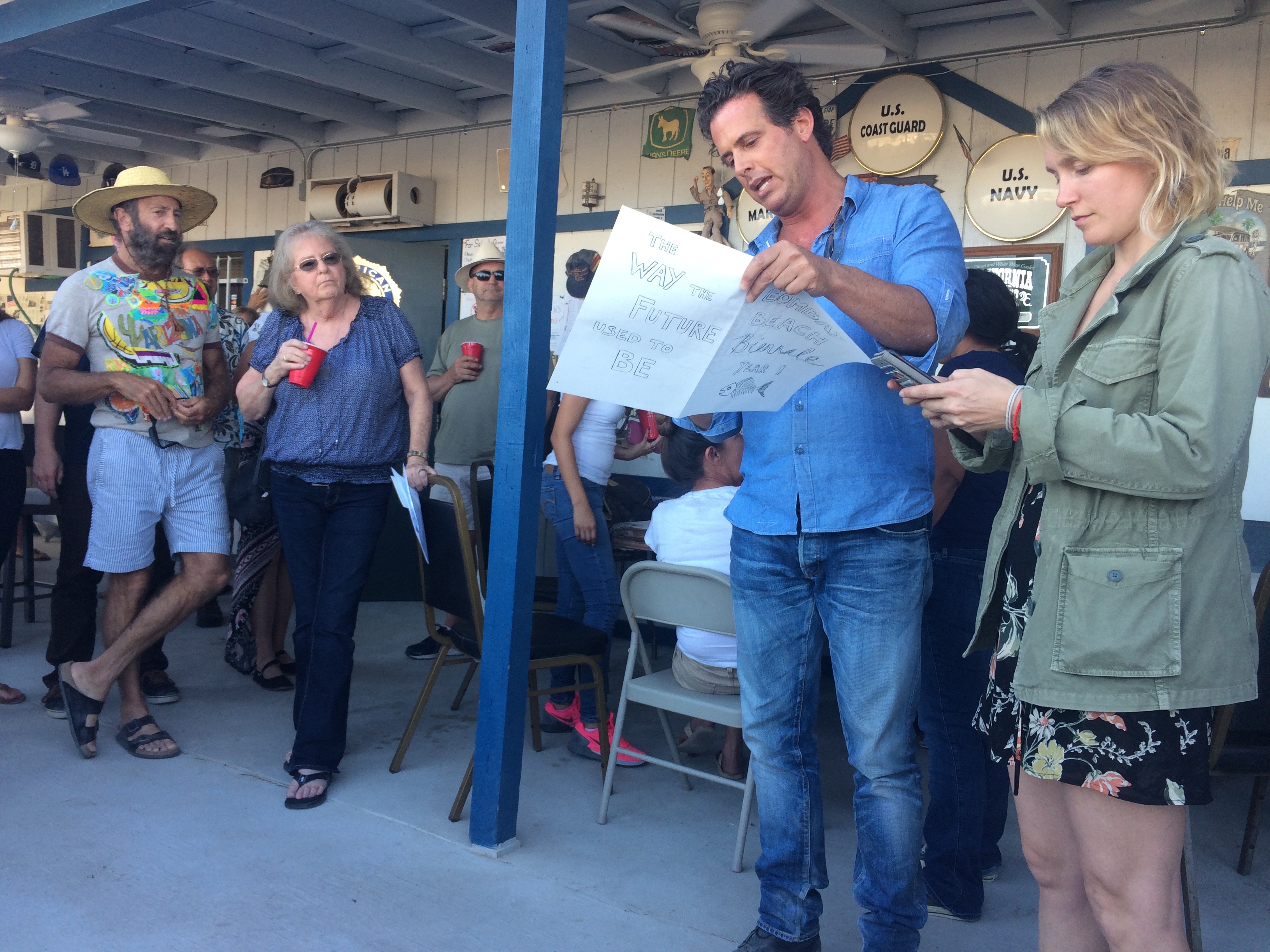

Stefan Ashkenazy, center, and Lily Johnson White, introduce the festival at the American Legion Post

“For those of you who live in Bombay Beach, it might be strange as to why we’re doing this,” says Stefan Ashkenazy, who co-founded the festival last year along with the Italian American filmmaker Tao Ruspoli and the artist and Johnson & Johnson heiress Lily Johnson White. Ashkenazy, who owns Petit Ermitage, a boutique hotel in West Hollywood, is tan with a mane of dark wavy hair and a preference for wearing monochromatic ensembles in gauzy white or head-to-toe denim. “You are so authentic. You are so yourselves,” he says from the wooden porch of the American Legion Post, attempting to explain his attraction to the tiny town with a population of roughly 300. “If you’re not from Bombay Beach,” he says, “you’re curious, you’re adventurous.”

With that, the procession takes off on golf carts, dirt bikes, bicycles, and four-wheelers down E Street to tour the neighborhood turned festival grounds. Ashkenazy recently purchased several abandoned properties here—he says the homes with power and water can cost anywhere between $20,000 and $30,000 each—and he and his crew of artists have been in town for weeks gutting and rehabbing them, sometimes working with locals to dispose of toxic waste they found rotting inside. One property was missing a roof and several walls when Ashkenazy bought it and handed the keys over to New York artist Greg Haberny. The place is now known as the Hermitage Museum, its pristine white walls filled with abstract paintings and sculptures made mostly of wood and other junk Haberny scavenged from the streets.

An installation on the beach

If Bombay Beach feels like an unlikely place for an art festival, that confusion is by design. The festival began as an absurd joke about what would happen if the Venice Biennale—the esteemed art fair held in Ruspoli’s native Italy, where he comes from a royal family—were held in rundown Bombay Beach. “Why don’t we do like, a really high art festival and not play up the decrepitude of place, but rather, try elevating it in the most amazing, somewhat playful way?” Ruspoli told me over the phone several days before the festival. Spread only through word of mouth, the date and details of the event are kept secret, Ruspoli says, not because he wants it to feel exclusive—although it inevitably has that effect—but because he doesn’t want to overwhelm the town with too many people. And because there’s no financial gain involved, Ruspoli says, the festival’s aim is straightforward: “To both take down the art world a notch and take up Bombay Beach [a notch].”

Ruspoli, a filmmaker who’s working on a documentary about what it means to be monogamous—partly inspired by his own tabloid-strewn divorce from actress Olivia Wilde—says he started visiting Bombay Beach about a decade ago to photograph it and eventually bought a place there. He noticed that other artists and film crews often shot there, too, but then once they shot their footage, they often fled without a trace. “There’ll be like, a fashion shoot or a music video shoot or something, but the town had nothing to show for it,” he told me. “All this creativity was happening here and movie shoots and everything, but no, nothing stays, and [there’s] nothing for the locals to be proud of.”

The unavoidable truth, of course, is that when the Biennale ends on Sunday, little of its manic energy and enthusiasm will remain here, either. But that doesn’t mean the organizers aren’t trying to contribute. Ashkenazy says locals are encouraged to visit the Hermitage Museum by asking for a key at the Ski Inn, the town’s other bar. The so-called Bombay Beach Opera House, a previously trashed home they renovated and painted swimming pool blue, may also play host to future performances. The organizers also dream of turning the drive-in movie theater, comprised of junkyard cars rescued from the area, into a fully functioning theater the locals can visit year round.

Local residents Janet Geonzaque (left) and Kyrstal Worden (right)

But for now, the locals are enjoying the rare spectacle of crowds of young people descending on their town. Or at least most of them are. “Some of the people here are really grumpy about it,” says resident Scheherazade Jones, turning her face into a scowl to mock her neighbors. “They’re just used to, I think, the quiet little town, but it’s time for this town to be like it used to be, you know, back in the day.”

Ernie Hawkins, another longtime resident, agrees. He sees the Bombay Beach Biennale as a sign that the town may be experiencing a revival of sorts, despite the environmental disaster looming near its shores. Before the “new blood in town” began to buy and fix up some of the old houses in the neighborhood, he says, it was slowly dying—literally. “We were having three funerals a month out here,” he says, before becoming distracted mid-sentence by the strappy thigh-high gladiator sandals worn by a woman across the street.

“I always tell people it’s an eerie kind of beautiful,” says Jones. “When you go out on the berm and you’re by yourself and you look out at the sea and how it’s receding and stuff, you know, to me that’s kind of eerie but beautiful.” Maybe that contradiction is what keeps so many people enamored with Bombay Beach, which has been the subject of several documentaries and is so desolate that even its Instagram geotag lists it as “ruins,” as if the remains of its former pier was the archeological site of a deceased civilization. “This place is a long way from being a money tree,” Hawkins says. He looks around at the sun-kissed women in crop tops and platform boots who look like they could be dressed for Coachella, the massive music festival taking place less than an hour’s drive away. But here, he says, “They didn’t have to pay to park. They got to feel free. It’s freedom. Where else can you find this kind of freedom?”

By dusk, the beach party on the shores of the Salton Sea is in full swing, and everyone appears to be feeling extremely free, with the aid of a little liquor and a cool desert breeze. A bartender clad in a yellow speedo doles out free cocktails from behind a yellow bar branded with the words “Bombay Beach Club” while women in floral sundresses with paper parasols dance to 1960s French pop music. Some of the locals, in T-shirts and shorts, sip bubbly drinks on striped lounge chairs and look out at the sea beyond. The fading sunset casts a glow of deep purple along the horizon, and if it weren’t for the overwhelming smell of the water and the dead fish washed up on the sand, it almost feels tonight like Bombay Beach is a thriving resort town once again.

Follow Jennifer Swann on Twitter.