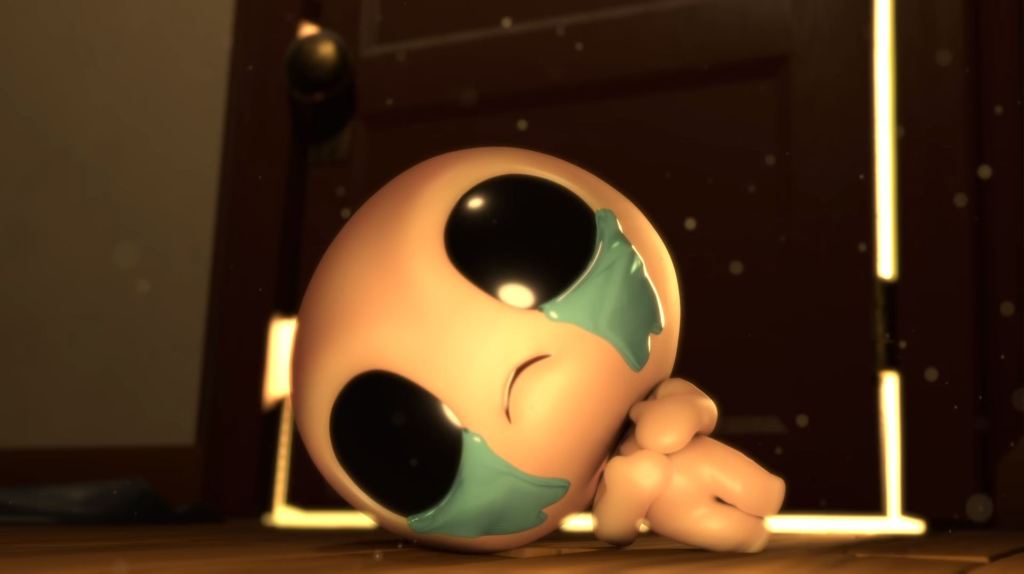

It’s been seven years since Super Meat Boy, arguably one of the best platformers ever made. Super Meat Boy‘s designers, Edmund McMillen and Tommy Refenes, have teased a return to Super Meat Boy over the years, but it’s never come to fruition. And while Refenes hasn’t released a game since Super Meat Boy, McMillen has been incredibly prolific, with the surprise success of his Zelda-inspired roguelike, The Binding of Isaac, dominating his time the last few years. The End Is Nigh, released this week on Steam, marks a return to the genre that’s his siren song.

For The End Is Nigh, McMillen partnered with programmer and designer Tyler Glaiel. The two had previously collaborated, prior to Super Meat Boy rocketing McMillen into the spotlight. Both Glaiel and McMillen got their starts on Newgrounds, a Flash-based community. (Several are in The Basement Collection, a package of McMillen’s oddities.) Glaiel is best known for Closure, an excellent puzzle game that played with light and dark.

Videos by VICE

The prospect of a new platformer from the co-creator of Super Meat Boy is alluring, but check your expectations at the door. While The End Is Nigh shares a design ethos with that classic—first and foremost, it’s hard as hell—The End Is Nigh is undeniably its own thing. It’s not a sequel to Super Meat Boy, and crucially, the pacing is exactly the opposite. Whereas Super Meat Boy had players sprinting through on a timer, focused on ratcheting up the death count, The End is Nigh has no such timer and moves at a much slower, more puzzle-centric pace.

The setup for The End Is Nigh is, of course, vague and bizarre. The world has ended, I guess, and you’re one of the last things left behind? Everything else has been destroyed, or, more accurately, mutated. For whatever reason, you embark on an adventure that takes you on a perilous path, and along the way, you collect “tumors.” These work similarly to Super Meat Boy‘s bandages; the more tumors you collect, the more secrets you can unlock. They’re an optional but satisfying challenge that quickly lead to other optional but satisfying challenges. There’s a tumor in each stage, with occasional five-in-one bigger tumors in secret spots.

And though you might be tempted to wall jump, key to scaling Super Meat Boy‘s gauntlets, there’s no such option here. In The End Is Nigh, players have a more limited moveset. You can jump, crouch, and hang onto ledges. Once on a ledge, it’s possible to hold left or right to pull a long jump, one with a tiny arc to it. If you hold down a trigger, you can fall off anything and ensure you catch a ledge.

So much of playing Super Meat Boy is rooted in raw instinct. The controls are nimble enough to give players the ability to save (and screw up) without giving it a second thought, and every death feels earned by the player’s own mistakes. The End Is Nigh operates similarly, but you spend a lot more time studying how the level works before embarking on a single jump, and the game actively encourages players to pause, take a breath, and study the next move.

One big reason for pausing is The End Is Nigh‘s emphasis on exploration. Super Meat Boy had its secrets, yes, but McMillen’s penchant for layering his games with mysteries came into full bloom with The Binding of Isaac. The End Is Nigh continues that tradition, and lord knows what McMillen and Glaiel have hidden beneath the surface. If it’s anything like The Binding of Isaac, we may not know everything the game is hiding for weeks, months, or years. But it didn’t take long to realize The End Is Nigh wants you to poke everything around it. An otherwise normal-looking wall might actually be passable, allowing you to enter a new area. As a “bonus,” those hidden areas are often guarding the game’s most challenging sequences.

The End Is Nigh is technically separated into stages, but you can pass between them at will, and upon return, the levels reset. This seems totally benign, until you realize the level design takes this into account. Many secrets can’t be accessed until you “beat” a stage, head to the next one—and come back. Certain ledges will only be accessible if you’re attacking them from the “completed” side.

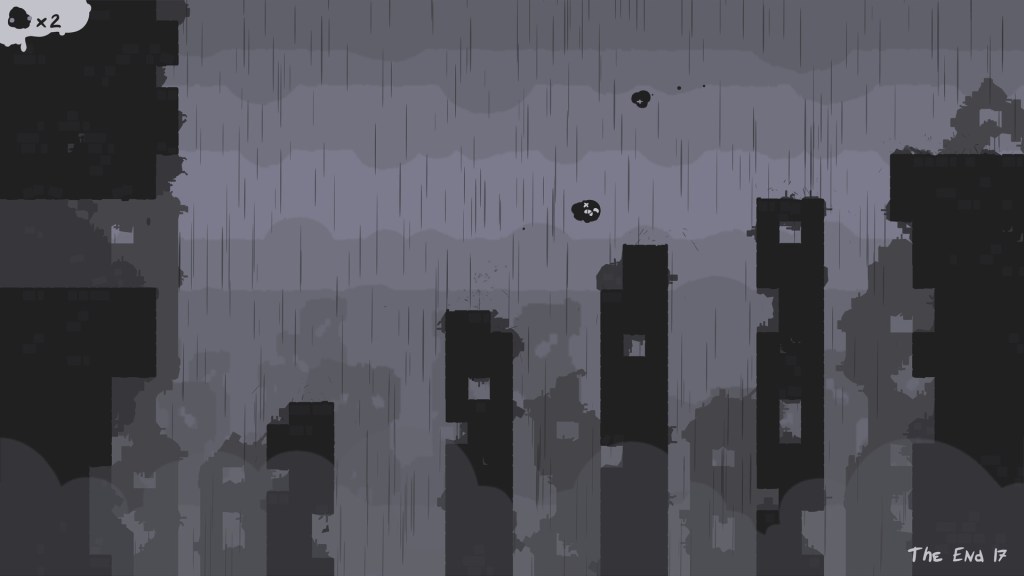

Take, for example, this secret area:

It only gets more complicated from there, but I’m loathe to spoil exactly how; the surprises are half the fun. More than a handful of times, I would trigger the environment to shift in one direction or another, not knowing why or how. It can be as simple as grabbing the right ledge or jumping to a certain, out-of-the-way spot. In the nearly three hours I’ve spent with The End Is Nigh, more of it has been spent trying to decode its secrets than making tough jumps.

This isn’t to suggest The End Is Nigh is easy, but in the early hours, if you’re focused on moving forward, rather than excavating its many secrets, platforming veterans won’t have trouble pressing on. Eventually, though, the game gives players a chance to choose from a few different worlds, and that’s where the difficulty spikes. McMillen and Glaiel are no longer messing around.

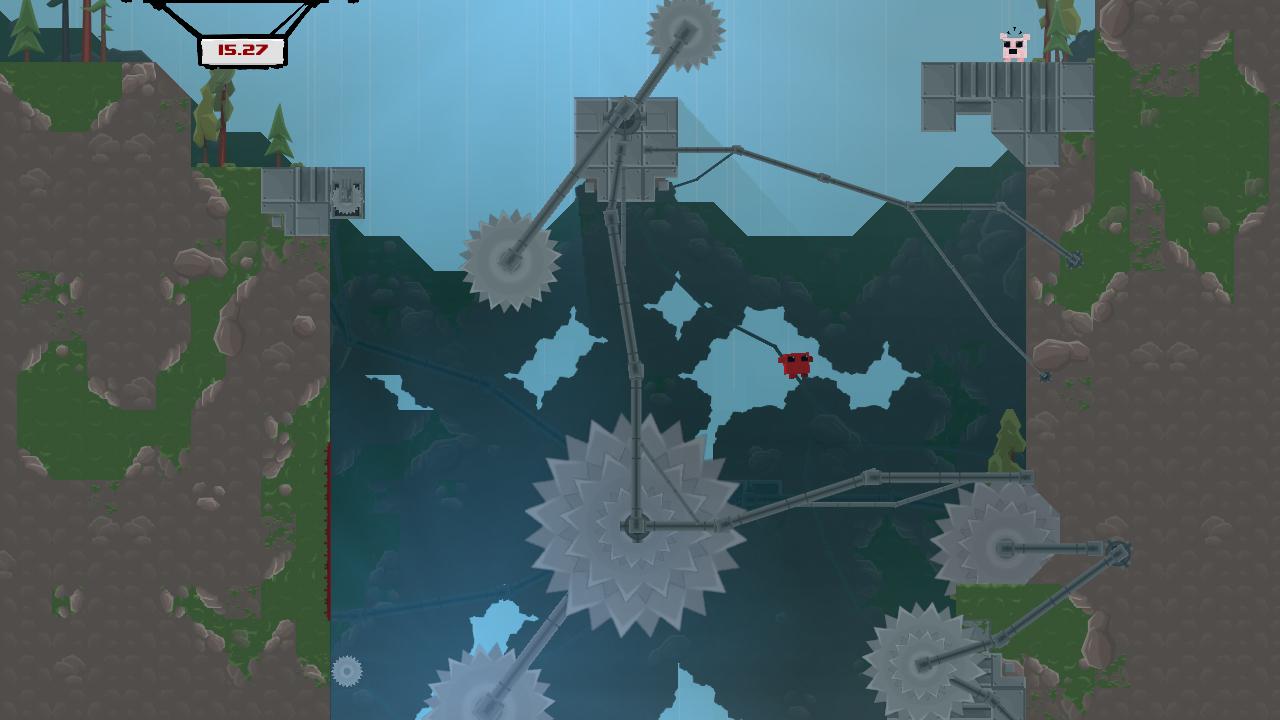

A world of lava-based stages, in particular, had me fuming (in a good way).

Look at that shit!

Moments like this produce a righteous anger I sometimes crave from platformers, demanding everything from me, mentally and physically. I don’t necessarily need that from, say, Super Mario Odyssey because Nintendo’s aims are different. (Though I sure would like to play an ultra challenging platformer from Nintendo one day; I’m sure they’re constantly pulling punches!)

It’s impossible to think or talk about—or play—The End Is Nigh without invoking Super Meat Boy because The End Is Nigh couldn’t exist without it to riff on. But that places an enormous burden: “Hey, can you be an all-time classic, too?” I don’t know if The End Is Nigh can hang with Super Meat Boy, as I’ve yet to finish it and it’s tough to declare anything in the heat of the moment, but I know this: it’s a hell of a lot of fun.

Follow Patrick on Twitter. If you have a tip or a story idea, drop him an email here.