For years, the DEA secretly paid workers inside U.S. agencies and companies for access to user data, rather than going to a court to obtain a search warrant for such data. That included paying sources inside the parcel industry to open and reroute packages; airline industry sources who provided flight itineraries, dates of birth, and seat numbers; and workers at private bus companies who provided daily lists of passengers who bought tickets in cash.

Paying moles inside companies allowed the DEA to passively monitor some services for potential targets without the friction of going through the courts, where such broad surveillance could be denied outright. In some cases, the DEA used the information to seize money or drugs from people. But buying the information in the first place may in some cases skirt Fourth Amendment protections.

Videos by VICE

Now, a pair of bipartisan lawmakers are pushing the Department of Justice to tighten policies around confidential human sources that would ban the practice entirely across the DOJ, including the DEA and FBI.

Do you know about any other cases of law enforcement paying for data? We’d love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, Wickr on josephcox, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.

After the revelations of the DEA paying for information came to light in 2014 and 2016 reports from watchdog bodies, the DEA said in its own letter to Senator Chuck Grassley that the agency had updated its policy to ban payments to employees of other agencies or quasi-government agencies. But recently Senator Ron Wyden’s (D-OR) office was told the DEA’s policy still allows agents to pay employees inside private companies for access to data. The new letter, led by Senator Wyden and also signed by Senator Cynthia M. Lummis (R-WY), aims to plug that loophole, which could see agents sidestepping the warrant process to simply purchase data from moles inside companies instead.

“The Congressional Research Service informed Senator Wyden’s office that DEA officials said the agency does not apply the prohibition on payment for information obtained in the course and scope of a source’s employment to employees of private companies,” the letter reads. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) is a federal legislative branch that provides Members of Congress with policy reports and more.

“The DOJ must explicitly prohibit these practices to ensure that all of its components, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the U.S. Marshals Service, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) do not use confidential sources to avoid using appropriate legal processes to obtain Americans’ data,” the letter continues.

Ordinarily to obtain information from a company, the DEA has to go through the courts. That might involve an application for a search warrant, which is then approved by a judge. This is a fundamental part of the U.S. justice system, and is to ensure that the DEA has authority to request the data, that the request is not overbroad, and there are reasonable grounds to invade the privacy of the target, such as them concretely being suspected of a crime.

Over the past several years, law enforcement agencies like the DEA, CBP, and the FBI, as well as sections of the military, have been buying data from data brokers. This has included smartphone location data collected by ordinary apps. Critics argue that such data should ordinarily require a warrant to obtain after a Supreme Court ruling in 2018 which related to cell site location data. The agencies, instead, simply buy access to the data from private companies.

Wyden and Lummis are worried the federal government isn’t just buying from data brokers, but that it might be buying data directly from people within companies, which bypasses the warrant process.

“If the DEA wants data from a private company, it should be serving that company with a warrant, subpoena, or other applicable legal process, not circumventing Americans’ privacy rights by paying off employees,” Riana Pfefferkorn, researcher scholar at the Stanford Internet Observatory, told Motherboard in an email. “These payoffs should be illegal, not merely subject to the whims of an agency’s policy, and private companies should take disciplinary action against employees who sell out their customers to the government.”

A 2014 report from the Amtrak inspector general’s office found the DEA paid an Amtrak employee more than $850,000 over a nearly 20-year period for confidential passenger data. Senator Grassley then asked the DEA for answers. In 2016, the Office of the Inspector General published a report on the DEA’s management and oversight of its confidential source program. Much of the framing of the report was on waste; that is, a focus on how much the DEA was spending on sources. The report mentioned but did not focus on the issues around the Fourth Amendment and unreasonable searches and seizures that the DEA paying sources inside companies raises.

The report included many more instances of the DEA paying workers inside companies and agencies for data. An airline employee received more than $600,000, and a parcel employee was given over $1 million, according to the report, which did not name the specific companies. The report also found the DEA used at least 33 Amtrak employees and eight TSA employees as sources. In one case the DEA paid a security screener to send information to the DEA about passengers carrying large sums of money. Payments to workers of other government agencies like TSA or quasi-government agencies such as Amtrak are now banned under the DEA’s 2016 policy change.

But a gap still exists for the DEA and other DOJ components to pay workers in private companies for data. Previous examples in the report include how airline employees provided the DEA with ticket purchase and baggage information, origin and destination airports, flight and seat numbers, and more information, according to the report. DEA Special Agents often received this information by email, text, or phone, and then used it to track down the traveler in the airport, the report reads. Often the agents seized currency from these people, it shows.

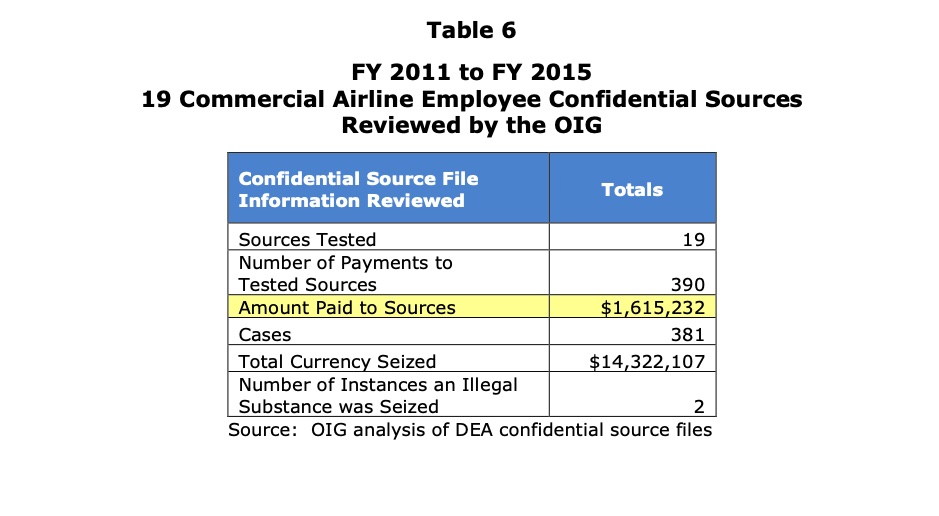

In another case, workers at private bus companies sent DEA agents information in exchange for payment. “According to a DEA Special Agent who specializes in using these Limited Use confidential sources, he tries to find individuals who can use their access to the bus company database to obtain passenger manifests for buses en route, the 2016 report reads. “When this DEA Special Agent uses this type of confidential source, he requests that the source determine, and manually annotate on the manifest, passengers who purchased their fares with cash and send the entire manifest to the DEA via email.” This sometimes resulted in the DEA seizing currency or illegal substances, the report adds. Nineteen sources were paid over $1.6 million, a table in the report shows.

“If the DEA wants data from a private company, it should be serving that company with a warrant, subpoena, or other applicable legal process, not circumventing Americans’ privacy rights by paying off employees.”

The DEA also paid sources inside mail reception companies, the report says (a mail reception company can include a company that receives and forwards mail for clients). The DEA hired these types of people because “they had access to company databases, access to parcels en route, or authority to administratively open parcels without a search warrant, which increases the potential for identifying suspicious parcels,” the report says. The sources sent information about the packages to the DEA and sometimes the packages themselves, the report adds. 5 sources received over $1.2 million in payments, a table in the report shows.

The FBI declined to comment when asked whether it uses any employees of private companies as sources, or whether their current policies allow it. The DEA, U.S. Marshals, and ATF did not respond to the same request for comment.

The Senators’ letter also asks the Department of Justice to identify each of the companies and non-profit organizations the DEA has obtained customer data from via its sources, and whether any DOJ component has paid a telephone, internet service, or other communication provider’s employees for customer data. The Senators gave the DOJ until May 8 to respond.

“I’m asking the Justice Department to provide transparency to the public about whether federal agents are currently using informants to buy data that would otherwise require a court order,” Wyden said in a statement. “If federal law-enforcement agencies are employing informants to do an end-run around the Fourth Amendment, that needs to stop, now.”

Subscribe to our cybersecurity podcast, CYBER. Subscribe to our new Twitch channel.