Oprah told my mom, and millions of mothers like her, what to think about a lot of things. Every day after middle school I would come home to the two of them, demagogue and disciple. The positioning of our living-room furniture was crucial to the experience: she in an armchair, occasionally riled up enough to talk back to the TV in angst or encouragement; me on the sofa behind, watching the back of her head and wondering what the hell was going on in there.

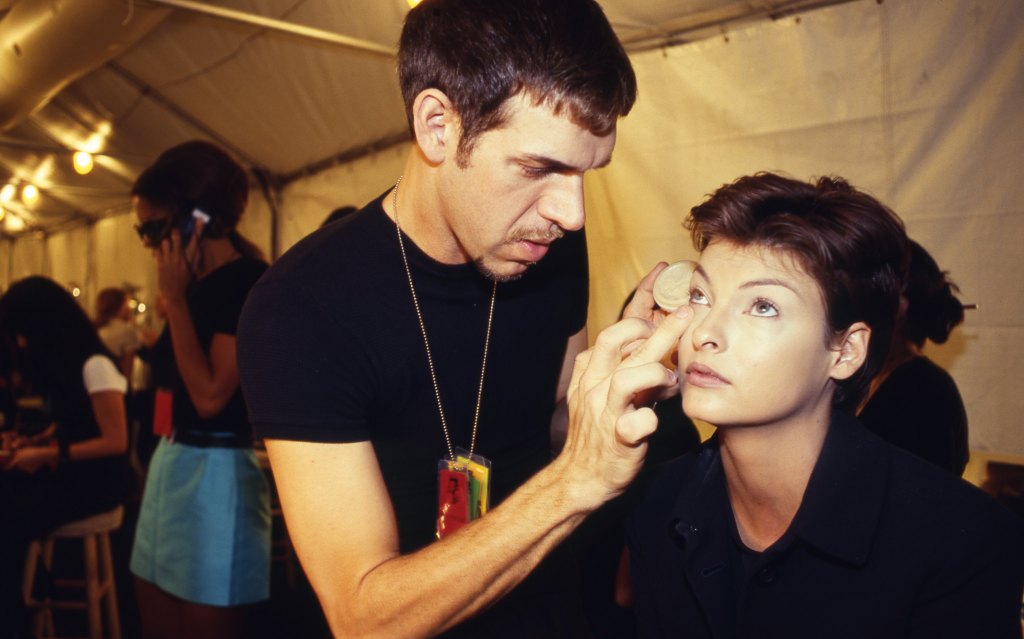

There’s one particular episode lodged in my brain, a makeover special featuring Kevyn Aucoin, one of the most famous celebrity makeup artists of all time. In the episode, he’s showing the studio audience a post-makeover photo of someone expertly styled to look like Linda Evangelista. They ooh and they aah. But then the photo’s subject is revealed, sitting right there in the midst of them all: not a woman, but a man.

Videos by VICE

The most shocking part about that transformation to my 12-year-old self wasn’t simply the reveal, but that one gay man could turn to another gay man and say, “Look at this very gay thing we did” on national television. And have an audience clap for them. And have my mother watch them—God forbid she see anything of me in him. It would be another five years or so before I came out to my parents myself. Aucoin died 15 years ago this month, but only recently have I found myself able to appreciate his work—and his unapologetic, unmissable queerness.

Aucoin had a very particular way of speaking, his voice husky with a slight sibilance. He was tall and thin and wore tight T-shirts, a uniquely gay aesthetic that prevailed in the 90s and early aughts as seen on Will & Grace and, later, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. Aucoin’s sexuality was tactile, oratory, and inescapable at a time in my life when I ran so hard from my own.

Men like Aucoin were “flaming,” with overly articulated eyebrows and meticulous speech patterns, hair tips fringed with gold, wrists expressively lax. “Mine is the story of the ugly duckling, about being able to see that you’re not what everyone around you is telling you that you are,” he told the New York Times in 1994. “I became interested in the idea of transformation. Where it stemmed from, for me, was the awareness from a very early age that I was gay, then hearing how awful and evil that was. Eventually I realized that was all lies, and then I started questioning what else I had heard that wasn’t true.”

My younger self also knew what it was like to be gay, and how awful that was—how awful you were, and how it felt to be alone with your loneliness and self-loathing. Growing up, I was only aware of my femininity as a problem to be solved, a way of walking and talking that I slipped into and out of with caution. I couldn’t just be myself. I’m sure my father hoped “feminine” might be a phase I’d grow out of, watching my face light up at the gift of a Cinderella Barbie one Christmas, asking for gymnastics lessons the next. Who I am now would have scared the shit out of who I was then.

In the foreword to Aucoin’s bestselling book, The Art of Makeup, former Allure editor Linda Wells wrote that cosmetics are “about thumbing your nose at authority, testing your sexuality, and, really, defining yourself on your own terms.” That idea was on my mind the other day, while I got my makeup done at Barneys’ beauty counter. My skin was glowing—a fact handily corroborated by standers-by—as the saleswoman, clad in all black, moved her hands assuredly across my face. She combed my lashes into shape and applied cream blush to the high points of my cheeks, handing me a mirror after each step.

I apologized profusely for how often I found myself blinking (nonstop), and we talked about whether or not eye makeup should be applied before or after your foundation is set. (Applying foundation after you’ve done your eye makeup makes it easier to wipe away eyeshadow fall-out.) The lashes ended up a little heavy for my taste, but I looked snatched. Possibly snatched af. And it occurred to me that what’s lost in popular discourse around makeup and beauty is that it’s not about caking on product to hide who you are, but about having the courage to be the most you can be. To say look at me without shame. For me, it’s about being the person I would never let myself be 15 years ago.

Aucoin died of complications relating to a pituitary brain tumor in 2002. “Makeup helped me survive my past,” he said in a speech at a Council of Fashion Designers of America awards ceremony in 1995. And it is makeup that is helping me to write my present, to take pride in my features and articulate what I want for myself, and on what terms. I don’t know what my mom thought while watching Oprah and her very gay makeup artist all those years ago, but today, I don’t really care. Aucoin’s unabashed femininity may have scared my tween self, but I sure as shit am unafraid now.

Follow Sean Santiago on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Metavision Studios -

Screenshot: Ubisoft -

Screenshot: Bethesda Softworks -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki