An excellent way to ruin a perfectly civil dinner party is to bring up the topic of seal hunting in Canada. How heated does seal-talk get? Pop singer Morrissey argued in 2014 that Canada’s then-Minister of Fisheries and Oceans should have “her head blown off” with a high-powered rifle for not abolishing the hunt. She retorted that Morrissey is “desperate for a hobby” and has been “brainwashed by decades of propaganda.” Either way, seals continue to be hunted off Canada’s icy North Atlantic coast. Seal meat is also increasingly becoming available at restaurants across the country—and as Morrissey’s beef with the ministry indicates, there’s a great deal of conflicting information coming from both sides of this debate.

To find out what’s really happening, I worked alongside MUNCHIES on a documentary exploring the controversy. We spoke to seal hunters from Nunavut, Newfoundland, and Québec—as well as organizations that have long opposed the hunt, such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW). Alongside interviewing leaders of the animal-rights movement, we embarked on snowmobile and speedboat seal-hunting expeditions at the frost-blind ends of the earth. We also joined Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at a raw-meat feast in Iqaluit during his election campaign.

Videos by VICE

The seal hunt is a complex political issue, even for those seeking to investigate it in an impartial manner. Animalist groups have spent decades reinforcing the idea that harvesting seals is among the most barbaric, gruesome, and cruel acts humankind can perpetrate. Their message is simple enough: seals look as adorable as big-eyed puppy-dogs and killing them seems not merely brutal but utterly pointless.

WATCH: Canada’s Controversial Seal Hunt

Those who actually live alongside seals see things differently. Canada’s Inuit have depended upon seals for millennia as a source of food, clothing, and fuel. Few people outside the Arctic Archipelago realize how crucial seals are to the northern economy and way of life. To this day, the inhabitants of Nunavut continue to hunt, eat and sell seal meat and pelts—as do their non-indigenous neighbors in Newfoundland and Québec’s Îles de la Madeleine —regardless of public outcry, sanctions and anti-sealing campaigns. But as their markets have shrunk or disappeared, many are now claiming that save-the-seal activism has destroyed their livelihoods.

My interest in this story began when a chef in my hometown of Montreal named Benoit Lenglet started serving dishes like seal poutine and seal loin at his restaurant Au Cinquième Péché. Other restaurants soon started doing the same, including Maison Publique, also in Montreal, and Côté Est, in Kamouraska (which makes a Phoque Brigitte Bardot Burger – the bilingual homonym phoque meaning seal, in French, and Brigitte Bardot being one of the original celebrity opponents to the seal hunt). I then heard of restaurants in Newfoundland such as Raymonds and Mallard Cottage also featuring seal on their menus.

Vegan organizations like PETA often stage protests when they realize that a chef is using seal meat, such as this one in January, where an activist in a seal costume “writhed in a pool of ‘blood’” outside a Vancouver restaurant serving ethically-sourced seal ragu pappardelle. Canadian chefs regularly receive death threats from animal rights groups for offering seal, yet they are adamant that there’s more to seal meat than an attention-seeking gimmick. They argue that an organic, wild-harvested, local and sustainable protein like seal is precisely what diners should be eating—especially if the animals continue to be harvested for their pelts.

As we started shooting our film, we learned that Iqaluit-based filmmaker Alethea Arnaquq-Baril was making a documentary ( Angry Inuk) that examines the devastating effect animal-rights policies have had on her community. The film is out now and has won awards at The Santa Barbara International Film Festival, Canada’s Hot Docs Festival, and TIFF’s Top Ten Film Festival. As a result, a long-overdue discussion about the issues around seal hunting is finally starting to happen. The success of Angry Inuk has already caused certain animal rights leaders to question their policies—and in some cause begin to acknowledge the damage they’ve caused.

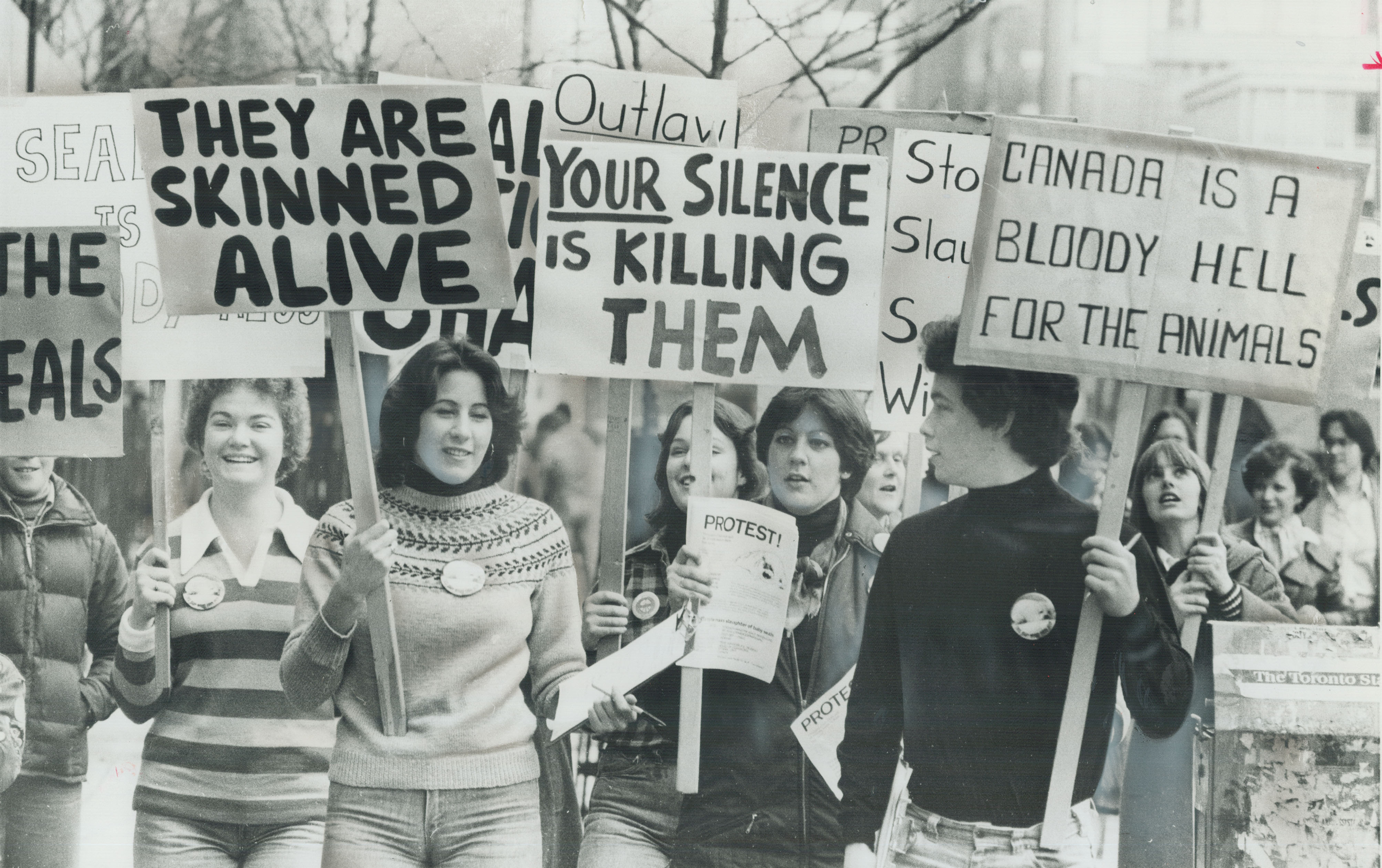

Films have long played a central role in the seal hunt polemic. The global anti-sealing movement can be traced back to Les Grands Phoques de la Banquise, a sensationalistic 1964 film that aired repeatedly on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and in Europe. This black and white documentary features staged and falsified scenes of animal torture that are devastating to watch to this day. Its manipulated footage of seals being skinned alive outraged the world, galvanizing resistance from animal welfare organizations.

In speaking with veterinary scientists, we learned that the most humane way to kill an animal is by doing so in the fastest way possible—as is done by professional sealers who follow a three-step procedure designed to reduce or eliminate suffering.

While it was important to make changes to the sealing industry back then, as populations had been dwindling, all parties now agree that seal species in the Arctic Ocean and off the Grand Banks are nowhere near endangered today. “Canada’s harp seal population is estimated to be 7.4 million animals, almost six times what it was in the 1970s,” notes Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the governmental organization that monitors the hunt. The animal rights movement has been so successful in protecting seals that herd populations are continuing to grow, even as fisheries officials attempt to manage threatened fish populations in those same waters. An adult grey seal can eat approximately two tons of other marine species in a year, with cod (whose stocks are famously imperiled) accounting for up to 50 percent of its diet. Can we honestly argue that environmental stewardship means permitting a healthy species to consume vast stocks of an at-risk species?

Why is it socially acceptable to eat factory-farmed burgers, for example, but not to eat sustainable wild meat such as seal?

The more we consider the seal hunt, the more questions we raise about ourselves. For example, given humanity’s unflagging omnivorousness (between 87 and 96.3 percent of Americans eat meat, depending on the survey), are ethically-sourced wild animals preferable to domesticated animals? Why is it socially acceptable to eat factory-farmed burgers, for example, but not to eat sustainable wild meat such as seal?

In speaking with veterinary scientists, we learned that the most humane way to kill an animal is by doing so in the fastest way possible—as is done by professional sealers who follow a three-step procedure designed to reduce or eliminate suffering. (More on that here.) The hunt today is, ironically, less cruel than what farm animals go through at slaughterhouses. Why, then, are Inuit and maritime sealing communities still portrayed as inhumane monsters by animal-rights groups? Clubbing baby whitecoat seals has been outlawed for decades, yet such videos keep popping up as fundraising tools on social media. Could it be that militant animalists are focusing on sealers because they are an easier target than industrial agri-producers?

READ MORE: Eating Seal Meat Is a Vital Part of Life in My Community

Those who profit from save-the-seal fundraising exercises admit as much: “The harp seal is the easiest issue to raise funds on,” explained former Greenpeace activist and current Sea Shepherd CEO Paul Watson in this 1978 interview. It’s worth listening to. Seals have been generating immense profits for special-interest groups for over four decades now, with little consideration given to the coastal communities that have been affected by “save-the-seals” campaigns.

According to the Ontario Federation of Humane Societies: “The simple fact is that there is no possible chance that the [Atlantic harp seal herd] is in any danger of extinction, and it’s ridiculous for anyone to suggest that… The greatest immorality in the seal hunting controversy has been the reckless, deliberate campaign of racial discrimination and hatred which has been deliberately fostered against the people of Newfoundland and of Canada by groups and individuals whose primary aim is to raise funds.”

Our film asks whether, in the anti-sealing crusaders’ important struggle for animal rights, something even more fundamental has been overlooked: human rights.

Inuk lawyer and sealskin fashion designer Aaju Peters contends that animalists knowingly targeted Inuit livelihoods by lobbying governments around the world to ban the import of seal products. Although the seal hunters of Nunavut still utilize every part of the animal, as they have always done, there are almost no remaining markets for their pelts. Groups like PETA and IFAW have generated fortunes to “protect” a healthy, unthreatened species while Inuit communities struggle with endemic poverty and food insecurity—despite being surrounded by one overabundant, fully sustainable resource: seals.

“We spent 250 years convincing the First Nations and Inuit to hunt as part of the European organized industrial chain,” notes John Ralston Saul, a Canadian author and public intellectual. “We wanted aboriginals to stop hunting for their own needs and to start hunting for our needs. So we got them to reorganize their society on our behalf. And then suddenly, the great-grandchildren of those Europeans stand up and say, ‘What a dreadful lot of people you are; you’re horrible and we certainly won’t have any of that anymore.’”

READ MORE: Seals Are Delicious, So Let’s Kill and Eat Them

Our film asks whether, in the anti-sealing crusaders’ important struggle for animal rights, something even more fundamental has been overlooked: human rights. “We rarely get our voice heard on the issue, so we’d like to tell our side of things,” explains Angry Inuk director Alethea Arnaquq-Baril. Their side is finally starting to be heard, at a time when many urbanites remain so detached from their food supply that they’re oblivious to the fact that their breakfast BLTs require the slaughter of actual pigs.

Seals eat and seals get eaten, regardless of our opinion on the matter.

Industrialized society has trouble accepting the fact that it is possible to care about animals and kill them for food, clothing, and other purposes. Yet this dualism is “at the very origin of the relation between man and animal,” notes John Berger in his classic essay “ Why Look at Animals?” “The rejection of this dualism is probably an important factor in opening the way to modern totalitarianism.” Berger’s point was that, when we start forgetting nature’s basic laws, we gradually lose our ability to recognize other foundational truths. Every life form in existence transforms other forms of life into sustaining energy. Does the wolf shed tears over its sheep dinner?

These days, the only animals most of us remain close to are pets—we don’t remember what animals, and humans, are like in the wild. A seal is not a pet, though in its cuteness it may resemble one. A seal is simultaneously an aquatic predator and an aquatic prey. It isn’t something meant for cuddling. It is a beautiful, sentient creature that kills and gets killed. Seals eat and seals get eaten, regardless of our opinion on the matter.

We, too, are predators—even if we’ve found ways to mechanize, and largely conceal, that process. Our rational, urban selves struggle to compute the truth that humans kill to live. We also possess a conscience, the ability to be structurally compassionate toward nature and thereby act as protectors even as we destroy swaths of our surroundings and the environment at large.

To better navigate this vexed relationship with wildness, we might consider seeking the guidance of those who actually live in proximity to it. Inuit and Atlantic Canadian seal hunters have always shared their coastal lands with marine mammals—and as climate change accelerates, they won’t be silenced any longer. However we may want to define ourselves, the truth is that all of us—including the seals—are in this together.

This first appeared on MUNCHIES in June 2017.

More

From VICE

-

An octopus cyanea hunts with a blacktip grouper on one side and a gold-saddle goatfish on the other. Photo: Eduardo Sampaio and Simon Gingins -

A villager who was lucky enough to survive a tiger attack and his scar. All photos by Rana Pandey -

Marilyn, an attorney and former professional dominatrix, poses for a photo with her sub who is fully encased in latex on the Vancouver Fetish Cruise. Photo by Paige Taylor White. -