Clash between Byzantines and Arabs at the Battle of Lalakaon (Wikimedia Commons)

This article is the beginning of a series on Europe’s Medieval martial arts guilds, known as the “Masters of Defence.”

Videos by VICE

The Middle Ages in Europe are often described as dark times in which there was a dearth of philosophy, of learning, of general culture. Thus, the Renaissance, a renewal of all of those things was celebrated, and continues to be celebrated today, as Europe’s rise out of the dark ages. And the Middles Ages were indeed rather crude times, in which illness ran rampant, illiteracy was common, and the church, as the arbiter of Europe’s entire social structure, eradicated the pursuit of art for art’s sake as extravagance. The Crusades may be, in their own way, the apotheosis of the Middle Ages. Yet in this time of dank living spaces, poor hygiene, forced religiosity, and baleful delight in the macabre, the Masters of Defence, elite swordsmen with a passion for improving martial arts pedagogy, arose.

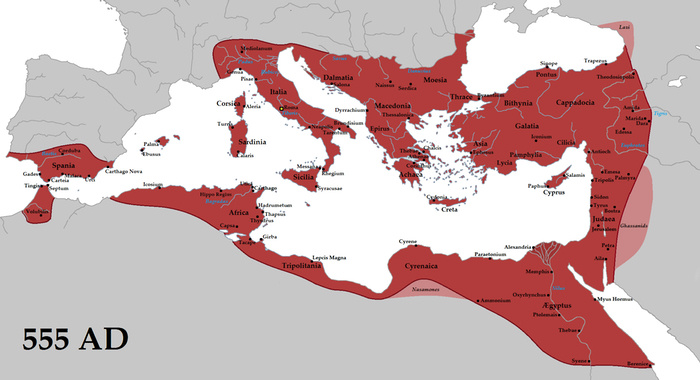

But why did martial arts proliferate in the Medieval and early Renaissance period in Europe after being seemingly forgotten in the ensuing 800 years after Rome fell? The phrase ‘fall of Rome’ is technically a misnomer, since only the western half of the empire collapsed in 476 A.D. There are innumerable reasons for the decline and subsequent end of the western portion of the Roman Empire, ranging from invasions by the Visigoths, to economic hardship, to natural disasters, to the hubris of overreaching territorial conquests. As the West weakened, the eastern portion of the Empire grew stronger and when the collapse of the West finally occurred, the East continued, operating as the new iteration of the Roman Empire. Referred to now as the Byzantine era, the Eastern Roman Empire remained a dominate force in Europe and Asia Minor for the next 1,000 years. As an extension of the Byzantine reign, many Roman and Greek traditions were upheld by the citizenry, although the primary religion went from the polytheistic pantheon of Roman gods to the singular Christian god.

Most historians believe that after the fall of Rome in the 5th century, Europe devolved into a nearly constant state of battle as the Teutonic tribes invaded and fought throughout various parts of Europe and as many of the Christian nations engaged in warfare with the Islamic nations in the Middle East. Europe was certainly fighting in the post-Roman Empire eras, but the art of fighting and the application of fighting methodology, practiced as sport, gave way to constant fighting on the frontlines. There could be no time for sports like boxing, wrestling, and even stick fighting when one was constantly conscripted into war. In addition to the need for men to act as soldiers rather than athletes, there was an ideological shift as the Roman Empire and its culture of violence and excess became subsumed by the sedate, yet militaristic, Byzantine Empire.

The Empire at its greatest extent (Wikimedia Commons)

1,000 years of Byzantine culture, religion, politics, and warfare cannot be condensed into a pithy statement or two, but the period marked an interesting turn in the European approach to fighting sports. The Ancient Greeks loved celebrating athleticism and prized the heavy events of boxing, wrestling, and the pankration as a national symbolic of strength and skill. Ancient Romans also enjoyed fighting sports and treated them more as a form of spectacle, as an opportunity see violence as entertainment. The Greek heavy events were also part of Roman sport, but their favorite combat sport was the gladiator contests that took place in the Coliseum. The Byzantines were, to be somewhat reductive, not terribly keen on sporting events. Athleticism was important only for the benefit of generating mobile and skilled soldiers. In the Eastern half of the Roman Empire, fighting was part of the culture, and it was a warring culture rather than a sporting one.

The rise of Byzantium did not entirely wipe out the pursuit of fighting sports. The Pankration continued in parts of the Byzantine Empire in the first few centuries. The capital city of Constantinople hosted athletic events, but by the time that Christianity was firmly situated as the primary religious authority, fighting sports like wrestling, boxing, and the Pankration, which were synonymous with paganism, were no longer tolerated in the new cultural climate. Not only were competitions prohibited, the Byzantine Empire discouraged the practice and transmission of fighting sports because of their association with pagan traditions.

When Constantine the Great ruled the Roman Empire in very early 4th century, he decreed acceptance for those of the new Christian faith. In 393 A.D., Emperor Theodosius I eradicated all pagan festivals in the Empire. Although Theodosian code never explicitly discussed fighting arts, it did seek to eliminate all traces of paganism, which would primarily focus on the festivals and general gatherings that were associated with the sporting events of the ancient world. Thus, boxing, wrestling, the Pankration, and gladiator fighting no longer operated as large-scale entertainment and as consequence, the systemic practice of training fighting sports diminished. The only sport that the Byzantines truly embraced was chariot racing, which continued through the late Middle Ages.

In the ensuing years, as Augustine of Hippo, known as Saint Augustine, began pronouncing the new ideologies and moralities that would rule the Roman Empire. Saint Augustine decried paganism, and pointed to the horrors of gladiatorial combat in the Coliseum as the embodiment of paganistic excess. And thus, with the growth of religiosity, and the embargo on the traditions of the past, fighting as sport nearly disappeared in Europe and Asia Minor by the 5th century. Byzantium, while subsumed with war and religious conflict, no longer considered fighting to be sport or entertainment.

Byzantium rose from the Greek and Roman traditions, but unlike its predecessors, who happily engaged in both war and sport, the Byzantine’s dismissed sport as frivolity and instead, concentrated all its athletic prowess on creating a strong fighting army. There was no time, no energy, and no tolerance for petty games when there were holy wars to be fought.

The Byzantine their approach to warfare, which would remain nearly unchanged for 1,000 years, prioritized minimizing human loss and maintaining the borders of the empire against invading armies. The Byzantine military strategy operated in districts, called themes, of approximately 9,600 men and included cavalry and infantry that were mobile and ready for battle. Generals were not adverse to retreating if it meant minimizing loss of life, especially since nearby themes could swiftly come to their aid. This system organized Byzantium’s military force around the functionality of the group, and the efficacy of the theme, rather than any heroic ideology that may have propelled soldiers under the former Roman empire. Perhaps it was because of the religiosity of the Byzantines, who fought for the glory of God rather than any vainglorious conceits.

The Byzantine Empire perfected the institution of the military, maintaining a standing army of 150,000 men for over four centuries. Emperors emphasized the training and the general health of its army, providing medical service not only to those wounded in battle, but also to men who became ill. Illness was rampant in the close-quarters of ancient and medieval militaries. Army camps did not just include the military; civilians followed the military to provide services and/or conduct business, and nowhere was that transaction more prominent than in the attachments of prostitutes. Through prostitution, communicable diseases, such as syphilis, spread through the military. Later, when plagues swept across Europe, the armies of many nations would be hit particularly hard due to the close proximity of large populations of men. Plagues, of course, did not only impact the military. The infamous Plague of Justinian devastated Byzantium in 541 A.D., killing an estimated 25 million people in its initial outbreak. The Byzantine military could not combat this disease, but the institution of specific military medical care did help ameliorate the effects of many communicable diseases and elevated the care of soldiers, instilling an ethical prerogative for the Empire to value their soldiers as men and not just fodder.

Victory of Basil I over a Bulgarian in wrestling match (Wikimedia Commons)

The Byzantine Empire shifted in power and in the amount of land it controlled over its thousand-year reign. In the late 9th century, the Macedonian Empire established its place as head of Byzantium and under its control, the Byzantine Empire flourished, sparking a revival in arts and culture as well as expanding the empire’s territories. Interestingly, this revival included an apparent reintroduction of competitive fighting sports. Basil I, the first Macedonian ruler of the Byzantine Empire, reportedly won the respect of Emperor Michael III when, as a young man, he competed in a wrestling match against a Bulgarian challenger. Basil was from humble origins, and after making his way to Constantinople for an opportunity to better his circumstances, he found himself working as stable master for one of the Emperor’s courtiers. When Byzantium needed a champion to fight the Bulgarian wrestler, Basil was brought to the palace and, to the delight of Emperor Michael and the rest of the empire, he easily defeated the Bulgarian fighter. Basil eventually would become Emperor of Byzantium, murdering the very man who admired his wrestling prowess, and despite his ruthless accession to power, his reign marked the beginning of the Macedonian period in the Byzantine Empire and the cultural and political renaissance that followed.

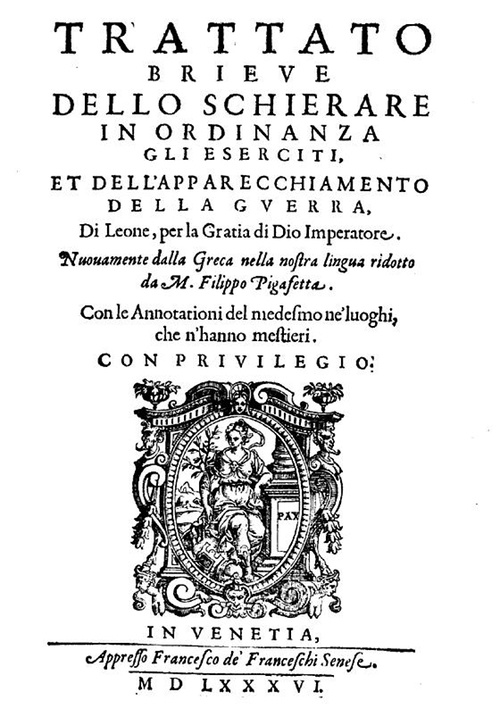

Tactica, Italian edition, 1586 (Wikimedia Commons)

The cultural renaissance included a turn towards pedagogy in the art of war. The Byzantines created a system of cavalry fighting that, while not negating the necessity of foot soldiers, focused on the efficacy of fighting on horseback. Emperor Leo VI, who ruled the Byzantine Empire 886 to 912 AD produced the seminal text, Tactica, which outlined the most proficient way to deal with a multitude of specific enemies in battle. Tactica advocated for soldiers to use sticks to practice swordsmanship and longer poles for the spear, and suggests war games where themes would divide into teams and practice fighting each other. This text, written (in full or in part) by the Byzantium Emperor, was a precursor to the flood of martial arts texts that would be produced in the Middle Ages.

The Byzantine Empire would also eventually fall, and in the last centuries proceeding its end in 1453 A.D., military stratagem shifted, as it often does, back to the prowess of the individual. Some of that progression may have been caused by a return to the solipsist ideology of the great fighters of antiquity, but it may have been instead an amalgam of the enthusiastic pugilism of Ancient Romans and the efficacious halcyon of the Byzantine military.

The Byzantine Empire demonstrated the cultural prerogative of valuing efficiency and skill in the pursuit of military might. Soldiers were no longer fodder for opposing armies, and instead were valued as a skilled unit. In the nearly 800 years following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, fighting had been focused on the military and the necessity of group fighting rather than on the individual’s pursuit of skill. But in the dankness of the Middle Ages, as disease and filth ran rampant, fighting literature moved away from the large military treatises and became focused, instead, on the individual’s attainment of fighting mastery.

One particular byproduct of the competent and puissant Byzantine era was the formation of guilds, comprised of skilled swordsmen, that created clear guidelines to what constituted an expert fighter in the Middle Ages. These Medieval guilds were functioned as small-scale versions of the Byzantium theme, yet instead of being charged with protecting a specific military boarder, these men, known henceforth as Masters of Defence, created a system of close-quarter fighting, utilizing weapons and empty-hand approaches. Their goal was to inject rigor into the transmission of fighting arts, and to establish an accredited group of martial arts instructors—no charlatans accepted. Nearly every country in Europe, including Greece, Spain, Turkey, Germany, Scandavia, the British Isles, Russia, and the Baltics, had Masters of Defence, fighting experts who worked to proliferate an integrated approach to fighting that included both armed and unarmed fighting styles. Not only were these guilds organized and professional, the masters wrote combat manuals that continue to be studied today. At a time when most writing was liturgical in nature, Masters of Defence across Europe, like Byzantine Emperor Leo VI before them, produced fighting manuals and dedicated their time to developing their combative skill.

In the 1,000 years after the Western Roman Empire collapsed, fighting as sport nearly disappeared as war became ones only prerogative to fight. It is a fascinating stretch often glossed over in fighting scholarship that skips from the Roman Coliseum to 17th century English pugilism. Fighting sports did not truly disappear as much as they were put on the backburner, waiting for the luxury of free time when individuals could afford to fight for sport rather than fighting for their very lives. The Byzantine Empire may have put an end to the Greek and Roman traditions of fighting for sport, yet it also inculcated a culture of precision and pedagogy that would eventually translate into an explosion of elite fighting scholars. It would not be until the 13th century that the Masters of Defence would emerge, across multiple European nations, and create a codified fighting system centering not on the military, the army, the theme, but rather, on the individual and his pursuit of excellence.