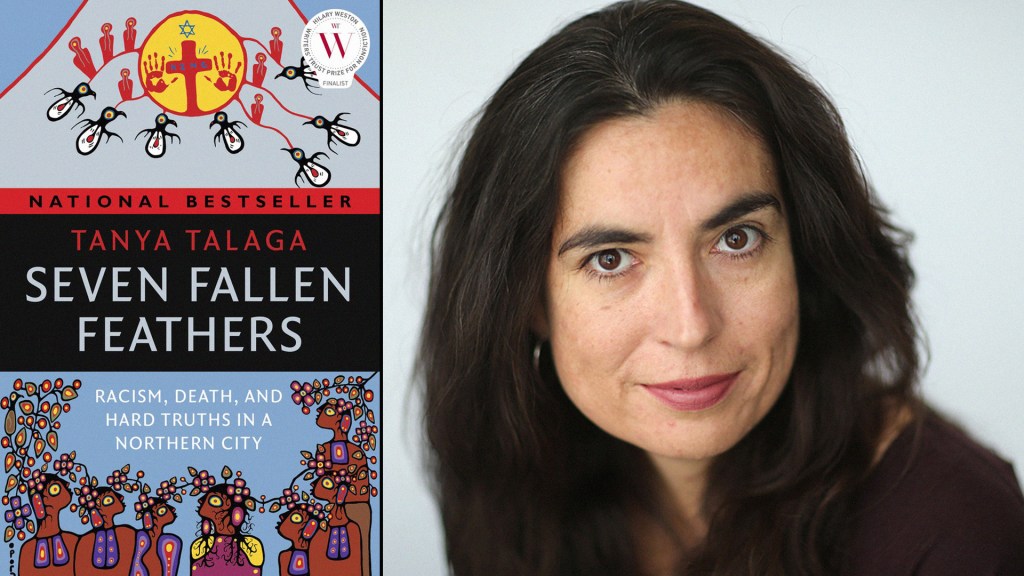

The following is an excerpt from “ Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern City” by Tanya Talaga. It explores the disappearance and deaths of seven Indigenous high school students in Thunder Bay, Ontario. All were hundreds of kilometres from the families, leaving in a city known for its racism towards Indigenous people.

It was Saturday, October 28.

Videos by VICE

Frost caked the ground outside of Stella Anderson’s home in Kasabonika.

There was a wolf staring at her. Stella drew in a sharp breath. A wolf always brings a message.

“LEAVE!” she said, trying to shoo away the animal before her.

The wolf gave her a final look and then it was gone. Two days later, Stella found out that her son Jethro was missing.

Her baby. Her eldest boy. Her first-born son.

Jethro Anderson did not go home on Saturday night. Jethro, who had just turned fifteen on October 1, never missed his curfew.

The last time Dora Morris saw Jethro, he was with her son Nathan, who was two years older than her nephew. Dora, a tiny woman with a mighty heart, was not only Jethro’s aunt, sister to his father, Sam; she was also Jethro’s guardian, his boarding parent, his second mom.

Dora was a mother figure to all the kids in the neighbourhood, who often congregated at the happy, two-storey home she shared with her husband, Tom Morris, in the Fort William end of the city. Dora was from Kasabonika Lake First Nation and Tom from Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug (Big Trout Lake) First Nation. Their descendants followed the animals and travelled when the seasons changed, settling high up in the northernmost region of Ontario. Human bones found on the shores of Big Trout Lake date back nearly seven thousand years, proving people had occupied this harsh and remote part of the world far earlier than the time of first contact with Europeans.

When Jethro was young, his father, Sam, and his mother, Stella, were having marital problems. To make things easier, Jethro lived with Dora and his cousins up in Big Trout. Jethro had two sisters, Lawrencia and Sarah, and eventually a younger brother, Clinton. Jethro loved his extended family and being with Dora and the kids.

Jethro was a kind soul, always finding new animals to befriend and bring home. From a very young age, he had an uncanny ability to calm other living things. When he was six years old, he had a pet owl he’d found in the bush. The white-and-brown barn owl had intense yellow eyes and a small, curved yellow beak. It would perch on his arm as he carried it around the rez with his pet dog scampering at his heels. Dora remembers it was a remarkable sight.

Dora, a slight yet physically strong woman with loose, curly hair, was a source of comfort and stability for Jethro. She was always there for him, and over the course of his short life, she gave him the family life and the stability he needed to thrive. She provided for him; she fed and cared for him. She treated him like he was one of her own.

Dora’s mind was spinning in circles on that first, awful, long night. She felt every tick of the clock as she waited for her nephew to walk through the door. As soon as the sun began to rise, Dora couldn’t wait any longer. She picked up the phone to try to get a hold of Stella.

She choked out the words. Speaking them made it harder — it made them true: “Jethro didn’t come home last night.”

The last time Dora saw Jethro, it was a Saturday afternoon. The boys were at home, anxious to go to the mall.

Nathan and Jethro had always been close. They had spent countless hours in the bush, climbing trees and using their slingshots to snag partridges for supper. Both spoke Oji-Cree until they were adolescents and moved to Thunder Bay where they shared a room, played video games, and hung out in comfortable silence on the couch.

Before Dora left for work at the Wequedong Lodge, a housing service for people travelling from remote First Nations into Thunder Bay for medical care, she gave the boys $2.50 each to buy a pop or a snack and told them to be home later for dinner. She told Nathan that he was in charge while she and Tom were out. Tom was an executive at Wasaya Airways, an Indigenous-run airline that services the remote communities in the north. When he went on a business trip, it usually involved an eight-hundredkilometre round trip on a puddle jumper plane.

Seventeen-year-old Nathan often looked after his younger siblings—Adrienne, who was twelve, and David, who was fifteen. Dora knew he was responsible, and that he and Jethro wouldn’t blow their 10:00 p.m. curfew.

When the boys left she went upstairs to get ready for work. Dora had been hired by the lodge to help the many elderly patients who didn’t speak English well or had lost the ability to communicate in the settlers’ language to time and dementia. She spent her days translating from Oji-Cree to English, so the caregivers could understand what the patients needed. Even at work, Dora was always busy caring for someone.

When she went on break at 9:00 p.m., she called home to see how the kids were doing. Nathan, David, and Adrienne were at home with their friends, but Nathan told her that he had separated from Jethro hours earlier and that Jethro hadn’t made it home yet. She thought this was strange and she began to worry.

When Dora got home from work at 11:00 p.m., she met Tom, who was just returning from another business trip, in the driveway. When they walked through the door, their kids were hanging out in the family room with their friends. Dora instantly saw that Jethro wasn’t there. She looked at Nathan and he told her Jethro still wasn’t home.

A few years back, they had gone through a similar experience when Jethro was twelve years old and staying with them in Thunder Bay. He had disappeared for a couple of days, though everyone in the small community knew he was staying at his girlfriend’s house. When Dora found Jethro walking along the road with his girlfriend, she had hauled him into the car and taken him home. But three years on, it was completely out of character for Jethro not to come home when he was expected, especially if he was out with his older cousin.

Nathan confessed to Dora that they hadn’t gone to the mall like he had told her. Instead, they went to their cousin Leeanne’s house to drink. Earlier that morning, Nathan had dropped off some beer, which he had gotten from a runner. In Thunder Bay, a “runner” is an adult over the drinking age of nineteen who buys alcohol for underage kids in exchange for a tip or some booze.

Nathan and Jethro had hung out that afternoon with Leeanne, her boyfriend Chris, her sister Debbie, and Starlight Frogg. Nathan didn’t stay long. He had promised a girl he was seeing that he would go visit her at the Intercity mall where she worked. He left Jethro at the house and headed for the bus stop.

Nathan would see Jethro once more that day, through the window of the bus. His cousin was walking down the street. He could have been headed to the corner store. He could have been going to the mall or to another friend’s house. Nathan didn’t know. All he knew was that Jethro looked happy.

Dora hid her rising fear from her kids. She and Tom told them not to worry; they were sure Jethro would be home soon. Just in case, she asked Nathan to go out and check with his friends at their usual haunts, to see if anyone knew where Jethro was.

While Nathan was out, Dora and Tom got into their van and drove up and down the residential streets — Victoria Avenue, Vickers Street, Balmoral, and Red River Road. Dora scanned all the doorways and the driveways, and looked down the sidewalks. They also cruised the Arthur Street strip.

After four hours, they went back home; it was 3:00 a.m. Nathan was there and reported that none of his friends had seen Jethro. Fitful, exhausted panic came creeping in. Dora spent the next few hours waiting, but to no avail. She decided to call the police.

“My nephew hasn’t come home,” she said.

“He’s just out there partying like every other Native kid,” the officer said. Then he hung up.

Shocked, Dora put down the phone. His comment felt like a slap in the face.

Dora began to make more calls.

The first was to Stella, who was more calm and measured. She believed her son would be home soon.

Next, Dora tried to find Sam, Jethro’s dad, in Kasabonika. He didn’t have a phone, so she called other relatives, looking for him. She thought about calling her own father and then stopped herself. She didn’t want to alarm him in case Jethro suddenly walked through the door. She called the police again, who said it was too early to file a missing persons report. Jethro had to have been gone for at least twenty-four hours.

When the sun came up, Dora and her husband went back out. Daylight was a blessing. One of Adrienne’s friends had told her the night before that a lot of the kids hung out at the Kam waterfront by the underpass and the tugboat, where they could drink. It was the first that Dora had heard that going to the river to drink was a popular thing to do among the teens.

Dora and Tom picked up Adrienne’s friend and drove down to the river. After the girl showed them the underpass, they drove her home and went back to search the area. There was no one there at that early hour. Clearing away the long grass and brush, they poked through litter and twigs, looking for any sign of Jethro.

They got to a wire fence near the underpass with a sign that read Private Property. Dora had her husband hold up the fencing so she could crawl underneath to see if her nephew was on the other side.

Nathan also went back out, canvassing the kids he met on the street. He got lucky. Somebody told him that Jethro was seen at the Brodie Street bus terminal, but that he stayed for only a short time before heading down to the river. The bus terminal was another popular meeting place for many of the students who didn’t have cars and travelled everywhere by bus.

When Dora got back to the house, Nathan told her what he had learned. She called the police again, asking if there were any leads. Her queries were met with silence. She was told again that maybe he’d be home later. When the party was over.

At 8:20 p.m., on Sunday, October 29, Dora walked through the doors of the Thunder Bay Police station and filed a missing persons report.

Follow Tanya Talaga on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

(Photo via Shawano County Sheriff’s Office) -

(Photo via Bonnie Blue / Instagram) -

Photo by Hollandse Hoogte / Shutterstock -

Eva Pascoe, founder of Cyberia, poses at the cyber cafe in London. All photos courtesy of Eva Pascoe, Ali Knapp, and Roger Green.