She had five aliases. She ran a gang. Rumor was she killed her own husband. And the police couldn’t touch her. So when Jessie Hickman first rode into the Australian town of Kandos in the early 1900s, the locals steered well clear. They also gave her a name: “The Lady Bushranger.”

This lady bushranger rejected every possible notion of what a woman should be, casting aside marriage and motherhood to roam as an outlaw. Dodging the authorities on horseback and terrorising the rural communities of regional New South Wales, she was just as extraordinary as the infamous bushranger Ned Kelly, one of Australia’s greatest folk heroes.

Videos by VICE

She had little interest in motherhood and gave her baby away.

And yet, her story never reached public consciousness. Australia already had its famed outlaw son; what did it need with an outlaw daughter?

Instead, Jessie was buried in an unmarked grave, and her story was left to rot alongside her corpse for over 60 years. This in contrast to the exploits of notorious male Australian bushrangers, who have been reimagined in contemporary pop culture as national heroes of Australia’s rural poor.

Ned Kelly, Australia’s most famous bushranger, as depicted in the 1906 film “The Story of the Kelly Gang”. Photo courtesy of Charles Tait – National Film & Sound Archive.

Similar to the American cattle rustler and the English highwayman, Australia’s bushrangers lived outside the law, surviving on their wits and guns. They robbed people of their livestock, held up towns, and killed those who got in their way. Unsurprisingly, many of these outlaws met a violent end themselves, either by gunfire or hanging.

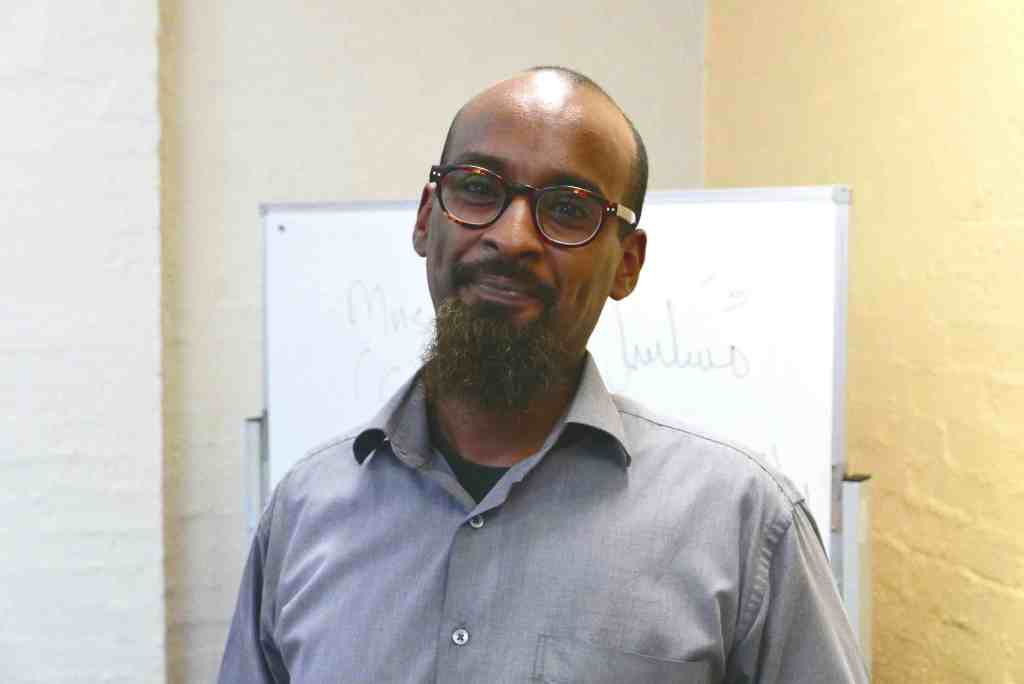

“The Australian bushrangers were very able horsemen. They were a completely different breed to the police and they basically ran rings around them,” says Carol Baxter, a historian and adjunct lecturer at the University of New England. This was in part because the official Australian police force was taught military horseback training, which was “completely unsuited to the Australian bush”.

Read more: The History of Erasing Women’s History

Thanks to illiteracy and the patriarchy, female bushrangers barely feature in the Australian national consciousness at all, says Baxter. “The history of women has been largely invisible because we only hear the stories, primarily, of the conquerors. And conquerors are men.”

She began gambling on horses and dogs to numb her grief, and supplemented these debts by stealing.

But Jessie Hickman, born in 1890, was also a conquerer of sorts. Her life was fast-paced and fraught with risk: By the time she was just eight years old, Elizabeth Jessie Hunt’s parents had given her away to a travelling bush circus, where she thrived. It was 1898 in the Australian state of New South Wales, and the prospects for a girl of Jessie’s low class and parentage were slim (her father’s criminal record didn’t help).

When her surrogate father, the circus owner, was killed in a freak accident, Jessie’s life began to fall apart. The circus folded in 1910, and she began gambling on horses and dogs to numb her grief, supplementing these debts by stealing.

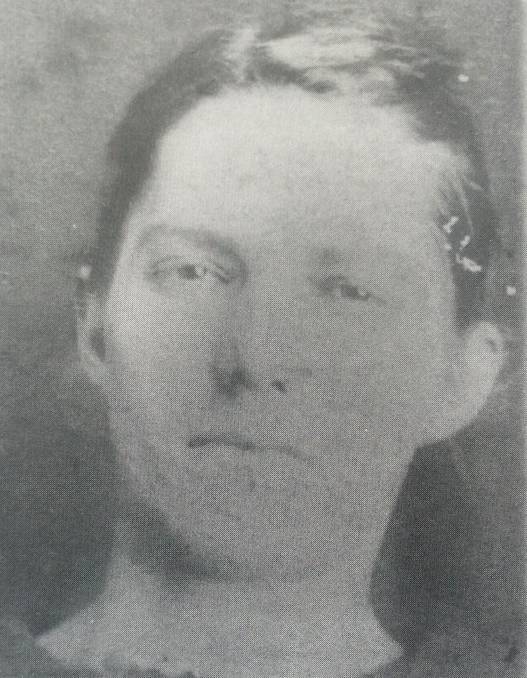

Domesticity was no refuge; it held zero appeal. In 1913, Jessie had a son to Benjamin Walter Hickman but gave her baby away. Not long after, Jessie’s thievery caught up with her, and between 1913 and 1916 she served two stints in Long Bay Gaol, one of Australia’s most notorious prisons.

Jessie’s police mugshot.

Released on parole in 1916 as a housekeeper for John Fitzgerald, a cattle-dealer in Western Sydney, Jessie learned how to sell cattle of dubious ownership (read: stolen). Although there is no record they ever married, Pat Studdy-Clift, author of The Lady Bushranger: The Life of Elizabeth Jessie Hickman, says Jessie called John Fitzgerald her “husband”, and that he was an unscrupulous character.

“He’d go to the pub and get very drunk and then he’d become violent,” Pat says.

If you believe the legends, Jessie Hickman—at various points—rode her horse over a cliff into a river while on the run from authorities, created an elaborate diversion to steal cattle in a police holding yard, escaped from custody while in a locked toilet aboard a moving train, and killed her employer John Fitzgerald with a chair leg. Though Pat says it was an act of self-defence.

Her antics soon caught the attention of local young men eager to share in her wild adventures.

“He picked up a chair to hit her with, the chair broke, and she got hit on the shoulder. She didn’t mean to kill him, she was just trying to defend herself,” Pat explains. There is no death certificate for John Fitzgerald, and his body was never found—”She hid it very, very well.”

In 1920, Jessie fled to the sleepy town of Kandos, near modern-day Wollemi National Park. But before leaving Sydney she married Benjamin Hickman, though apparently without any commitment to be with him. It’s possible Jessie wanted a new name and a fresh start, hoping to leave her past crimes behind her in Sydney.

The pair formally divorced in October 1928, with Benjamin noting somewhat cryptically in court that his wife “was very fond of animals—horses and cows—and wanted to live on the land.”

Three hours from Sydney, the cattle areas of Rylstone and Kandos border inaccessible and wild terrain, with cliffs and dark crevices dug deep into the mountainside. It was the perfect landscape for bushrangers like Jessie to disappear into. “Her skill on horseback enabled her to take cattle through those mountains where even the men wouldn’t dare to travel,” says Pat.

“Those mountains are very dangerous, very treacherous, and she could get through where men would not dare to try.”

The rough terrain in which Jessie roamed and lived for part of her life. Photo by Jennifer Gheradi.

Jessie would traverse steep ravines in the dead of night, herding stolen cattle on horseback under the cover of darkness. She rode astride like a man, and, to the unsuspecting eye, could pass as a cattle rancher. “She’d be dressed in men’s trousers,” says Pat.

A lifelong recluse, Jessie slept in a cave in the Wollemi National Park, situated high up a steep slope, but her antics soon caught the attention of local young men eager to share in her wild adventures. “She called them her young bucks,” Pat says.

With the support of these young bucks, Jessie had her pick of the farms across the Mudgee Region, herding stolen cattle up the mountainside before they could be sold off. Whether out of fear, or because Jessie only targeted certain farms, many locals stayed quiet.

The remains of Jessie’s cupboard, inside her hideout cave on Nullo Mountain. Photo by Jennifer Gheradi.

While she excelled in her profession, Jessie’s nonchalant attitude towards cattle ownership eventually brought her to the attention of the police, who were under enormous pressure to put her behind bars. They had made some headway into breaking up the “stray cattle trade,” but Jessie was now the leader of a whole network of bushrangers, and she had a knack for evading capture. So when the police finally got her locked up in 1928, they wanted to make the charges stick.

Fortunately for Jessie, on the day of her court hearing, the stolen cattle—which were the prime evidence—were stolen from the police. She was therefore acquitted, and “retired” to a farm hidden deep within the mountain gorge.

Less than a decade later, in 1936, Jessie was dead of a brain tumor, age just 46. She was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave at Sandgate Cemetery in Newcastle, Australia, where she remains.

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

Although Jessie’s late granddaughter came forward some years ago, Pat says there is still little to mark Jessie’s final resting spot. “It’s in the pauper’s part,” says Pat. “No grass, bare soil. The atmosphere there, I thought, was very eerie.”

Twenty years after she started researching Jessie, Pat is now 90 and blind, unable to make the journey to Jessie’s grave. But a feature film in the works about Jessie’s life, by Western Australia Director Jennifer Gherandi, could turn the site into a place of pilgrimage—not unlike what the Old Melbourne Gaol is to the infamous bushranger Ned Kelly.

And perhaps, finally, Australia will know the story of its forgotten lady bushranger.

Photo of Jessie courtesy of Pat Studdy-Clift.