Death is only sexy when it’s abstract: when it’s part of a story happening to somebody else, imbued with a sense of misplaced romanticism. In the wake of grief’s harsh and debilitating reality we often hide and try to make ourselves temporarily invisible. A bereaved artist will often take a hiatus in order to process and reflect on their mourning, before their public figure status cruelly obliges them to make some sort of insightful statement on the subject. In the case of a musician, they may write songs with lyrics directly relating to their loss, some time after the fact, usually when they have healed a little, when they are again on the ascendancy.

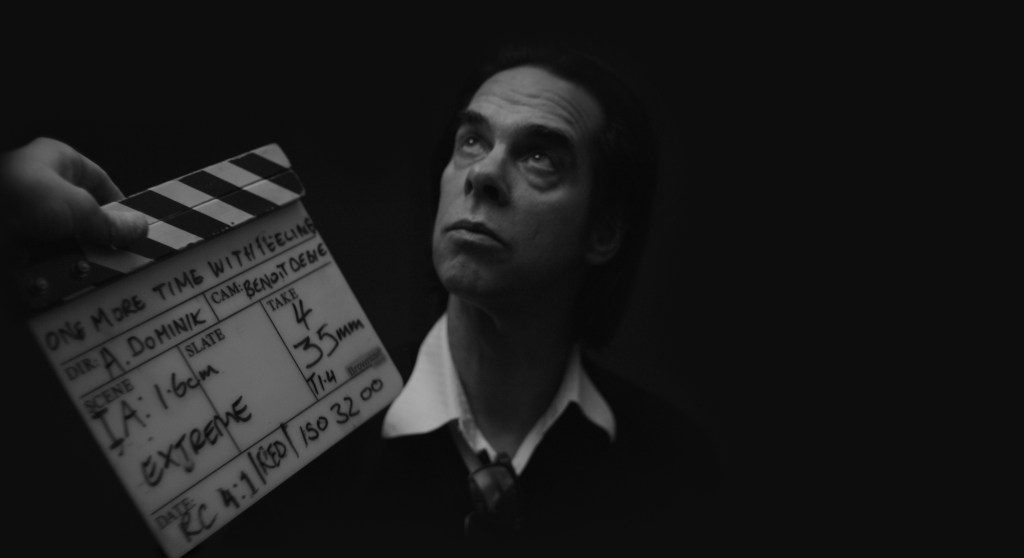

Nick Cave was never going to be so predictable. But his decision to make One More Time With Feeling, a new film released just over a year after the death of his teenage son Arthur who fell from a cliff, initially puzzled, even horrified me. Writing songs reflecting on personal tragedy may be one thing. Weaving the still raw subject through a documentary is quite another. Despite his decades long metier of murder and malevolence, that such an uncompromisingly robust and private individual as Cave would willingly invite us to witness his personal torment was previously unthinkable.

Videos by VICE

Ostensibly documenting the recording of the Bad Seeds’ 16th album, Skeleton Tree, the film is directed by Andrew Dominik (who Cave and band mate Warren Ellis previously collaborated with on the 2007 film The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford). Self-financed, to be shown only once in cinemas, the film aims to promote this new album without Cave having to engage directly with the press. As a result, the pervasive media speculation that has haunted Cave’s family since the tragedy happened is both answered and shunned. He’s simultaneously created an invitation and a full stop. It’s one of the few things he still has any control over and it’s a masterstroke.

But the music, despite its reverberating, resonant beauty is not what the film is really about. This is a document of grief and loss, but more strikingly, it is about trauma – a word that echoes through the film like a distant bell. The stuttering, spluttering shell-shocked Cave, struggling as he does to articulate, has made a definitive statement about the aftermath of a harrowing tragedy. An elegant but excruciating tribute to his sons, dead and living, it is a portrait of staggering vulnerability. The non-linear path of his thoughts and emotions are reflected not just in his statements to camera, but also in the audacious structure of the film itself. It eddies and flows, weaving sinuously around you, until all sense of direction has been lost. It lulls you with luscious visual beauty, but its sentiments are suffocating.

Cave has been the subject of a documentary before. The glorious semi-fictional biography 20,000 Days On Earth, released in 2014, was suffused with self-knowing and playful humour. In direct contrast, One More Time With Feeling is so unflinchingly truthful it hurts to look into the white noise of its bright centre, like peering into the heart of a star. Yet it also dances around the subject obliquely, never really facing the abyss head on. Always viewing the subject askance, as if through a veil, it wanders off in tangents before being pulled back violently via the elastic cord Cave references, which no matter how far he strays from the event, inescapably catapults him back to the epicentre of his pain and distress.

Despite the luxuriant black and white visual frames – Tarkovsky-like in their deliberateness and fluidity – there is nothing neat about this story. It’s messy, incoherent and understandably evasive. It has a tripartite structure which includes the recording process, a series of interviews with Cave and his wife and, perhaps most revealingly of all, a stream of consciousness narration which swims over the images. Cave’s demeanour – broken, diminished, aged – is astonishing. There is no “Tears in Heaven” sentimentality here but instead the enormous, crushing physicality of grief. We find ourselves watching Cave with the same ‘kind eyes’ of those stranger sympathisers in the bakery queue he balks at recalling.

Cave fears he is losing his voice and even the very chords of the songs he has written. Everything is dissolving, impermanent, destabilised. He is floating without anchor through a relentless sea of suffering. For a while now he has eschewed writing in a straightforward narrative style and here the fractured nature of his poetry has come into its own. The songs are not in themselves about the event (they were written before the accident), but their newfound weight suffuses every breath of Cave’s shambling, shattered delivery. It’s humbling to watch this intimidating character, recently so emotionally and intellectually concrete, appear so diminished. It is humanising.

The Bad Seeds studio craft is impeccable but there is an unfinished, unpolished nakedness to the songs, which emit the sense of moving through darkness as dense as matter. Cave visibly toils, stopping and starting these secular prayers, unable to find his footing. These moments would be bleak if it not for the blazing warmth and quiet unobtrusiveness of his right hand man, Warren Ellis, who Cave acknowledges is holding everything together. As he powerfully conducts the spiralling string section of the recording with a deft taloned hand, you feel thankful that Cave is in the care of this friend and faith healer. A much needed source of light relief, he steers everything back towards normality. Nervously faffing with his hair, Cave asks Ellis if it’s okay? “Best it’s ever been,” he responds, “proceed with absolute confidence.”

If the performance aspect seems raw it is nothing compared to the interview segments with Cave and his wife Susie Bick, which are quietly devastating. The event has shifted from the abstract grandiose domain of art into the personal, familial realm. These passages are hushed, tender and touchingly prosaic. The prophetic nature of some of the song lyrics are not lost on Cave, nor on his wife, who is superstitious about their sons as it is. Late in the film she holds up a painting she has recently found, admitting she at first shielded its discovery from Cave. Arthur’s infant hand appears to have painted the very place where he was to perish. Susie sees it as a calamitous sign, horrified by its subject matter and black frame. She hands it to her husband, sitting stone faced and silently beside her, wearing an incongruous tracksuit top. He fumbles awkwardly over where to put it down. It’s almost unbearable to watch.

However, the most devastating clarity and yet fruitless search for meaning is contained within Cave’s stream of consciousness narration; it’s here that we’re presented with the disjointed externalisation of the inner dialogue we all have. His thoughts and feelings are contrary, constantly shifting. He is untethered, a master of language now struggling aptly to describe anything at all. His voice and chords are not all he appears to be losing; even the words escape him as he tries in vain to renegotiate his place in the world. He’s correct when he says no one ever really wants to change. Change is forced upon you like a violent act. A different person looks out cloaked in the same skin. I’d argue even the skin is changed, its molecules rearranged in some fundamental way. He wonders conversationally where the bags under his eyes have come from.

There’s no sense of dialogue with the viewer, it doesn’t pose any questions; it just asks that you let the experience wash over you. The audience are pawns as much as Cave is. The final frame, as the credits roll, serves as the most poignant reminder as to what has been stolen: a bright shining life. A home recording of Cave’s sons singing a Marianne Faithfull song starts playing, accompanied by him on piano. “I’m walking through deep water,” they croon like their father, “trying to get to you”. Making this film is possibly the most honest and ultimately powerful thing Cave could have done. To know the family have decided to be happy, against all odds, is acknowledged as the act of revenge or defiance it surely is.

The potentially sensationalist aspect to this entire undertaking bothered me before I saw One More Time With Feeling. Was it exploitative, to both the Cave family and the audience? Was it emotionally manipulative? It is the opposite of that. With a great degree of dignity and personal strength, something noble and strangely hopeful has been created. Such truth telling is important, not only to his fans but also to anyone who wishes to better understand the human condition. There’s no bullshit about catharsis or loss serving as a muse. Cave admits he’s always looking for something to write about but that trauma has been undeniably damaging to his creative process. Imagination requires room to move, to grow. But there is none. Trying to make sense of this new reality, the struggle to find significance or permanence, takes up all space.

We are saturated with self-reflection and self-therapy through self-publication. Our emotional lives are unavoidably imbued with over sharing. If you’re in the public arena there’s a good chance the papers will know whose shirts you wear. We are anxious to know the details of things. But do we really want to know everything? I thought that we didn’t need this film, but I was mistaken. Cave has addressed one of the last taboos in art and in life, not just by so candidly speaking about the effects of trauma but in the way he has presented it to an audience. That grief is savage, disorientating, ineloquent and maddeningly open ended.

You can follow Anna on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

(Screenshots via Keith Lee / TikTok) -

Photo by NYU Langone Staff -

(Photo by VALERIE MACON/AFP via Getty Images) -

Photo: Ethan Miller/Getty Images