At the height of its popularity, a song featured in a Guitar Hero game could boost its individual downloads by as much as 843 percent. In the case of Dragonforce, the inclusion of the band’s song “Through the Fire and Flames” in Guitar Hero 3 boosted their CD sales by 126 percent. Guitar Hero: Aerosmith made more money for the band than any of their studio albums. Every time Stephen Tyler buys something, part of him should thank Activision.

Which is impressive, sure. Until you consider that for Guitar Hero this is just a notch on the belt. Since its debut in 2005, the Guitar Hero series has sold more than 25 million units, making more than $2 billion, and cementing itself as one of the best-selling video game series of all time. It was also a watershed moment culturally, with some of the largest bands in the world seeking out their own deals with Activision, hoping to cash in on the Guitar Hero boom. Guitar Hero left a sizable crater in the music industry and pop culture in general.

Videos by VICE

But it all had to start somewhere.

The story of Guitar Hero is one of a small developer and publisher, Harmonix and RedOctane, respectively, putting all their cards on the table, trying something new and unproven, with no track record or previous success to back them up. Over the course of just nine months in 2005, with no notions that the game they were working on would do more than break even, the two companies developed a game that altered the course of not only the game industry, but the world. Getting there required going behind people’s backs, ignoring the adults in the room, and learning how to focus a project and kill your darlings. It was guerilla, rag-tag, and made by people working for passion rather than financial gain. It didn’t hurt that the latter came in spades.

But things change and people sell out. Shortly after the success of the first two Guitar Hero games, Harmonix and RedOctane split up, both companies being purchased by separate publishers—Viacom and Activision, respectively. The former partners became each other’s biggest competition, as Harmonix went on to make the Rock Band series and RedOctane retained the rights to the Guitar Hero series, bringing aboard Neversoft to take over development. Regret and bitter feelings ensued. All the while Guitar Hero and Rock Band continued receiving out multiple yearly games, thousands of songs, and making billions of dollars each.

Until they didn’t. By the early 2010s, both series’ sales were on the decline. In 2010, Activision closed RedOctane. In 2012, Harmonix announced it had no plans for new Rock Band games—though it’d put out two new, less-successful Rock Bands a few years later—and was focusing on developing other titles. The whole thing burned fast and hot before fizzling out. Ask anyone who was there and they’ll tell you lack of innovation and oversaturation was the killer of both series. The genre never fully recovered.

To understand how Guitar Hero happened, you need to understand Harmonix and RedOctane. You need to dig back into their history, their ambitions, and their failures to understand why this game was a risk and why these companies were the only two that could make it what it was.

In an effort to tell the whole story, VICE has spent the last year tracking down and interviewing more than 30 people with a hand in the creation of Guitar Hero. From Harmonix and RedOctane, to Activision, to the musicians, retailers, and artists that made it all happen, this is the story of how one company with a lot of failures to its name and another company without a single hit to its name came together to accidentally change the world.

PART 1: THE LONG, WINDING ROAD TO UNCERTAINTY

The Axe

The brainchild of Alex Rigopulos and Eran Egozy, Harmonix Music Systems was founded in May 1995 with no intentions of being a video game development studio. Harmonix was established to deliver on a dream its two founders shared, something they’d been talking about and working on during their time as students at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where they’d also base their company. Rigopulos and Egozy, both musicians and lovers of music, wanted to bring the joy of making music to everyone—especially those with no musical talent. That was, and has always been, the mission statement of Harmonix.

It’s a statement that sounds great on paper. In practice, though, it was a failure at first. And that failure starts with the company’s very first project: The Axe.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): Alex and I were graduate students together, sitting in the same office at the Media Lab at MIT. [We were working under the director of the Opera of the Future group] Tod Machover, who was our professor at the time. We were working on all kinds of different music systems, but the one that we were most excited by was this idea of creating technology that lets anybody feel like a musician, or lets anybody create music like a musician, even though they might not have the skills of a musician. That was really fun.

When it came time to graduate, we really just wanted to keep doing that type of work, and of course no one would hire us to do that kind of work [laughs]. You have to realize, this is in the mid-90s, where, I think, the tech landscape was very different than it is today. And so Alex and I thought, “Hey, if we wanna keep doing this fun work of making cool music technology we should start a company doing that.”

And in fact, it was Alex’s idea to start the company. I thought that I might just go and get a standard, boring job at some software company. But Alex said, “Hey, let’s start a company. Would you want to join [me doing] that?” I didn’t have to think very long before saying, “Of course, that sounds amazing.”

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): You know, when we started the company—and this was back in 1995—we weren’t thinking of ourselves as a game studio at all. The co-founder Eran and I started the company to solve what we believed to be a problem in the world that needed solving.

Which is that just about everyone is born loving music and they’re born with this innate desire to make music, and just about everyone tries at some point in their lives to learn to play an instrument or learn to make music.

And almost all those people quit after a little while because they just don’t have the time or talent or patience or perseverance to muscle through the very protracted, laborious process of developing enough facility on a musical instrument to actually have a joyful music-making experience with it. And so the world is full of all of these very passionate music lovers and passionate air guitarists who have this innate yearning to make music, but just really don’t have an outlet to express themselves musically, so we founded the company in 1995 to try to solve that problem.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): The Axe was essentially Harmonix’s first project, and it was also the thing that was most similar to what we had worked on at The Media Lab. Essentially this way of letting someone create music by using a joystick.

Doug Glen (director, Harmonix): It seemed really intriguing that you could take these new technologies and they could be applied to allowing people who loved music but had no real training in music to create, compose, modify music in ways which were pretty profound. To do something that was more than just changing the beat or changing instrumentation, but actually changing music by telling the music what mood it should reflect and what tonal aspects it should have—organic or mechanical.

Dan Schmidt (game systems programmer, Harmonix): They wanted it to be to music like PhotoShop is to just screwing around with [pictures].

It was this app where there would be a musical backing track and then you would play a guitar, or piano, or saxophone, whatever, solo on top of it using a joystick to play higher notes or lower notes or faster or slower, and so on. The tech involved—and I worked on a bunch of that tech as well—it was really cool technology. It was kind of this music AI stuff [that tried] to take what you were doing with your joystick and turn that into something that sounded musical but was also basically following your instructions at a broad level.

That was the original product that the company was founded to make, and we finally got it out the door and it sold like 10 copies [laughs].

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): The Axe sold only a few hundred copies, despite us spending an enormous amount of effort both developing the product and trying to get it out there. I have to say, it was one of the more sobering moments of disappointment in our career as entrepreneurs [laughs].

Doug Glen (director, Harmonix): It didn’t [sell] because while it was really intriguing for about 15 minutes, after that, most people had tried it and chuckled at it and been amazed by it and were ready to do something else. And so they came to the conclusion that, at least in that particular version, they’d invented something that people would enjoy for a short period of time and then move on.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): It wasn’t until a few years into the business that the first music games started to appear, coming out of Japan and Korea. Games like Dance Dance Revolution and Beatmania. For me, the big one was Parappa the Rappa. I clearly remember the room that I was sitting in the first day that I booted up that game and started playing it and just had a grin on my face from beginning to end. That was the moment that I realized that rhythm action was an incredibly compelling framework for us to pursue the mission of the company, of bringing that joy of music making to the world.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): I remember playing that, and that might’ve been the first music game that I played. Certainly on console. We were playing that game and thinking, “Huh, OK, that’s pretty interesting.” It’s a music game, it has a lot of interesting story lines, it’s funny. The music interaction part is actually not particularly complicated—it’s just a sort of very simple call and response model.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): It was right around that time—when we decided to become a game developer, music game studio as opposed to just an interactive music developer—we started recruiting a lot of talent from the game industry. One of the earliest hires that we made was Greg LoPiccolo […] who came from Looking Glass Studios [developer of Thief and System Shock]. Before he was a game developer he had a storied career as a bassist in this rock band Tribe in the Boston area who I had seen many times live as a college student in Boston.

Greg LoPiccolo (project leader, Harmonix): Yeah, I joined in 98, sort of in the beginning of the games phase. Before they were not really a game company to begin with, and then I showed up late 98, and then early 99 a bunch of other Looking Glass people came over and we kinda pivoted into games.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): I remember this one meeting that we had, it must’ve been in either the late 90s or early 2000s, where Greg went up to the board and essentially drew a three-dimensional representation of the music track, with the idea that you could represent musical data in 3D, and maybe you could have these surfaces that were visible in a 3D scene and maybe you traveled across them or through them or something like that. […]

Normally, the way you think of music is that it’s sitting flat in front of you. Maybe it’s on a sheet of paper as musical notation, or if you’re using a digital audio workstation then you’re used to seeing these thin horizontal lines that represent the music or waveform audio. But here the idea was, “Well, let’s add a third dimension and have you traveling through the music.” We really liked that idea and essentially started developing some core concepts around it not even necessarily knowing what the game would be, but just knowing that this was the visual representation that we wanted for our music playground.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): [Greg] had a very specific vision of this game that we started prototyping and going after, and it was the game that eventually became our first published music game, which was Frequency.

Betting the farm

In 1999, as Harmonix was setting itself up as a game developer, on the other side of the United States in Sunnyvale, California, two brothers were starting their own company, an internet-based video game rental service called RedOctane. Founded by Charles and Kai Huang, the company functioned like rental services such as GameFly or Netflix. But as RedOctane’s former vice president of marketing Dean Ku recalls, “Their business took off, this one did not.”

RedOctane’s timing couldn’t have been worse. Shortly into the company’s history, the dot com bubble burst. For an internet-based start-up like the Huang brothers’ company, that was bad news. So they looked for new directions to take their business, holes in the marketplace they could fill. What they found was a video game genre that was big in Japan, but still niche stateside. A genre contingent on physical peripherals.

A year before RedOctane was founded, Konami put out the rhythm-based dancing game Dance Dance Revolution in Japanese arcades. To play, players stood on a small dance platform with four directional buttons they pressed with their feet to correspond with on-screen prompts. Dance Dance Revolution was a massive hit in Japan, prompting the publisher to make an at-home version for Sony’s first PlayStation console in 1999 complete with its own dance mat. While the arcade game also came to the United States in 1999, the PlayStation version of the game didn’t make it stateside until 2001. To play the game at home, people had to either find a bootleg copy or rent through a service like RedOctane’s. Only problem with this was they were only able to get the software. The hardware, or dance pad, wasn’t included.

It was a small hole in a niche genre, but a hole nevertheless. So RedOctane refocused its business plan.

Chares Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): At that time, we had an office on a street, it was probably a two block-long street. When the bubble burst, everybody started going out of business, to the point where that two block street, which probably had, I’m going to guess, maybe 12 to 15 buildings, there were only, like, two companies left standing [on that] block. Everybody else went out of business [laughs].

Dean Ku (vice president of marketing, RedOctane): But even during the dot com boom, and then bust, we almost ran out of money a couple times.

Chares Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): [We] needed to find some business that could be immediately profitable because there was nobody investing anymore; we had to run the entire business off of our own profits. At that time, we were renting games online, and this was, if you remember in the era of PS1, you could mod the PS1s to play import games. […]

And so people could play games from Japan, the Japanese versions of PlayStation 1 games, and so we were renting some of the Japanese PS1 games. At that time, the music games were hugely popular in Asia. Especially DDR. Dance Dance Revolution was hugely popular in Japan, but it had not made its way to the U.S. But people could rent them from our game rental service.

Dean Ku (vice president of marketing, RedOctane): We recognized early on, there was an employee, Andrew Kim, actually, who came to us and said, “Hey, there are these dance pads that people are looking for for Dance Dance Revolution, but in the U.S. you can’t find them.”

[Andrew Kim did not respond to VICE’s request for interview]

Chares Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): We couldn’t rent them the dance pads, but we thought, “Well, we could sell dance pads.” That was literally how we went from the game rental business, although we continued that, to discovering, “Oh, [there’s] this little niche market in the U.S. of people who wanna play these kind of crazy Asian music games.”

Dean Ku (vice president of marketing, RedOctane): So kind of just to try, we actually started sourcing some dance pads—put our logo on it, just because—and it actually did very well. Then because we realized there was a market for it it, we started developing this dance pad with a lot of different features that the hardcore players wanted.

From that, we kind of developed a name, did really well, went into retail, and that generated a lot of income and profits for us.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): If you went into a store in those days, there were probably two game peripherals that would sell for a $100 or more. There was the LogiTech steering wheels and there was our dance pads.

Dean Ku (vice president of marketing, RedOctane): We actually had a very good relationship with Konami for the most part because we helped sell the game significantly. They were not putting out dance pads at all, we proved that, hey, there’s a market here in the U.S.

We had this hugely successful PR campaign that essentially connected Dance Dance Revolution dance pads to kids losing weight, so there were a lot of schools who actually bought the combination to help kids in PE play games and then get healthy. That generated a lot of interest from the PR side and helped us, I think, foster a good relationship with Konami. But still, they were somewhat reluctant.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): We actually met a Konami executive on the U.S. side, and we said, “Hey, are you guys ever going to bring Dance Dance Revolution to the U.S.?” His response was, “Eh, I don’t think there’s much of a market for that in the U.S.” My brother and I looked at each other and said:

“If they don’t bring the game to the U.S., we don’t have a way to grow our dance pad business. And even worse yet, if they just decide to stop making DDR then we’re out of business.”

And that was when we realized, “Oh, I think we need to expand from just being a peripheral manufacturer, dance pad maker for someone else’s game to making our own game.”

At that same time, there was an arcade dance game released called In The Groove. We all saw it and everybody thought, “Hey, this is a pretty good game.” It was probably the best of the dance games that followed [Dance Dance Revolution]. It turned out it was made by a studio in Austin, Texas [called Roxor Games], and so we just kind of reached out to them out of the blue and talked to them. That’s how we ended up as a publisher—working with the developer in Austin to bring that game from arcades to consoles [in August 2004].

Corey Fong (senior brand manager, RedOctane): Not knowing that in general, because they [RedOctane] didn’t have the background of looking at sales numbers because they were still new to the industry, music games don’t sell. If you knew anything about business at the time, you’d be telling yourself that’s a crazy, crazy business strategy right there. But they didn’t know any better.

Dean Ku (vice president of business, RedOctane): And then that game was not very successful. And so we were thinking, “OK, we want to continue and look at other opportunities. So what would be another opportunity?” I think with dance pads, it never went completely mainstream in the U.S. Well, it did to some extent, but it was much more [popular with the] Japanese than for the American audience. So we thought, if you’re going to develop an instrument-based game with a hardware peripheral, in the U.S., probably the guitar or the drum makes the most sense.

Chris Larkin (creative services specialist, RedOctane): We were renting import games at the time, and a bunch of us liked playing some of the Bemani-style games like Guitar Freaks and stuff like that. We enjoyed Guitar Freaks but it is not a rock game. At all. Like, it has no rock sensibility.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): Even if you looked early on at say Guitar Freaks or Drum Mania, some of those games, you were holding a guitar and playing but sometimes you were playing to a jazz tune and you were playing to the drum track or you’re playing to a pop tune to the vocal track. There was no real theme except for you were holding a [plastic] guitar.

We had this idea that it should be about rock and metal and it should be about guitar, and sort of celebrating that legacy of famous guitar riffs and being a rock star on stage holding a guitar.

And so we had this idea that it wasn’t just about a crazy music game, but it was about letting people live that experience of being a rock star. And everything should be about that—the music should be about that, the characters and the game should be about that, the experience.

Dean Ku (vice president of business, RedOctane): We had these regular meetings where we talked about the business. I do distinctly remember that we came to a point where we had to decide, you know, what’s the next title. And I think for most of us, it made sense that we’d move into either a guitar or a drum-like peripheral.

Lennon Lange (associate producer, RedOctane): We knew that everybody wants to be a rock star. There’s nobody that’s like, “Oh, no, I wouldn’t want to be on a stage adored by fans just rocking the hell out.”

Dean Ku (vice president of business, RedOctane): But obviously it’s hugely risky; you’re committing millions of dollars towards getting a developer for the title, plus all the money required to actually build out the hardware. I mean, it’s a tremendous amount of money, so in many ways you’re kind of betting the farm on this next game.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): For us, we were like, “Oh my God, this could really break the company.”

Dean Ku (vice president of business, RedOctane): I wouldn’t say it was one single person that said, “Hey, this is our next idea.” It was just kind of a natural thought that, hey, if we’re going to do it in the U.S., it only makes sense to do it with a guitar or drum. But it took a lot of conviction on the part of the co-founders to say, “Yes, we’re going to bet the farm on this.”

In May 2005, Konami sued Roxor and RedOctane over what it alleged was an infringement of its dancing game patents. The suit was later settled in October 2006, with Konami acquiring the rights to In The Groove.

Who in their right mind?

Back in Boston, despite the fact video game development seemed like a better fit to achieve its mission statement, by the fall of 2004, things still weren’t going well for Harmonix. After shifting focus, staffing up with employees from other Boston-area studios like Irrational Games and Looking Glass Studios, and putting out the rhythm games Frequency and Amplitude, released in 2001 and 2003 respectively, the company had yet to reap any real successes from its labor. In fact, by and large, Harmonix had a lot more failures on its hands now.

But things were about to change, even if it meant making what, on paper, appeared to be the dumb decision. The two parties of this story, Harmonix and RedOctane, were about to come together.

Alex Rigopulos (founder and CEO, Harmonix): Frequency was very addictive. You really got into this kind of hypnotic music flow state. It was hard to put down. In the early playtesting, our playtesters were getting super addicted to it, and then the early reviews were incredibly positive and glowing. And then we managed to talk Sony into a television ad campaign for it. They spent millions of dollars on a TV ad campaign for that game. There was a moment where we thought that, finally, after years and years of struggling, we are gonna have a commercially successful product. We were very excited.

But then the game flopped.

There was actually an interesting story from Sony’s playtest process. Their process at the time was that they sort of created a one sheet, a sell sheet for the game with a screen shot and a few sentences about what the game was, and then they took all their playtesters and they asked them to rate their interest in the game before playing it. Then they let them play it for half an hour or so and then they had a survey after they played it and basically asked them about their intent to purchase the game after they had played it.

After they did that playtest session, the results that we got back from Sony and their report were that:

The pre-play interest score was the lowest score that they had ever received for any game they’d taken to test and that their post-play intent to purchase score [was] the highest of any game they had taken to test.

At the time we thought, “This is incredible! We got the highest score they’ve ever gotten coming out of playtest, this game’s gonna be a hit.” Right? But their marketing people said, “No, you don’t understand. This is terrible news. When we describe this game to people, no one wants to play it.” And they were right. You know, it was a game that, as fun as it was to play, it [was] incredibly difficult for them to market, then went on to be a commercial failure.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): OK, and honestly, the other issue was that Frequency was just kind of ugly [laughs]. I look at that thing now, and it’s like, “Oh man, that is not a pretty-looking game.”

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): Sony, God bless them, gave us the opportunity to make a sequel, Amplitude, which did a little bit better. But not too much.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): That game did look better. It still had this problem of being somewhat abstract. Like, “Who are you? What’s the player supposed to do? Are you a character in the game? Are you a spaceship? Like, what’s going on?”

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): Then Konami, who had been a fan of those games, gave us an opportunity to make singing games. We went on to make [the] Karaoke Revolution series for them and those fared a little bit better commercially. I think we did four or five titles for Konami after the subsequent several years. None of them were big hits, but they were turning a very modest profit. I think they didn’t have anywhere near that intense addictive gameplay of our earlier games, but they were much easier game[s] to market. You know, [if you saw a] sentence and a screenshot and if you were into Karaoke and games, you probably wanted to give this a try. Right?

Rob Kay (lead game designer, Harmonix): When Konami came along with Karaoke Revolution, the idea of having a live stage show performance where the player was the pop star in that case, that was a huge watershed moment, I think, for just how to bring music games to more people. Because obviously in Frequency and Amplitude, you were not a musician on stage, you were a spaceship blasting beats. It was inspired by old school arcade games, not by the fantasy of being a musician.

Eric Malafeew (systems lead, Harmonix): Sony came back to us, we’d made Amplitude and Frequency with them. They said, “Well, we don’t really want to make another music game with you, but we have this EyeToy camera.” We basically demonstrated that we could make kind of wacky games, or unusual, novel games on a budget and on a time table. So they gave us the freedom to make a game called AntiGrav, which was our one and only non-music game. It’s basically SSX in the future where you did everything in front of the camera. The rule was you weren’t allowed to touch a controller.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): We released that game in 2004, and it was OK. It was fun, it was cool, you were controlling the character on screen with your body. But in most respects, it was a pretty mundane extreme sports game, right? What then happened in the marketplace was that we got the lowest review score on that game of any game that we had ever released. It was, like a 72 or 74. Not bad, but not stellar. We were used to glowing reviews.

We released this kind of middling reviewed game for the EyeToy and then commercially it went on to sell four times better than the best music game that we had ever released.

That was a real gut punch for us. At that point we were nearly 10 years in. We were about nine and a half years into the existence of the company and we had just released our one non-music game and it was our worst reviewed product that sold four times better than our best reviewed, best game had sold. At that point there was this real moment of doubt where we’re just wondering, like, “Why are we even doing this? Does the world just not want what we’re selling?” We were having furious conversations about whether we just needed to, I dunno, close the studio or reinvent the studio and go after something completely different.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): I don’t think we were talking about closing the studio, because actually, as far as the business side of it goes, we were doing fine. It’s not like we were doing amazing, but deals were coming in. We were working on games, we were working on them pretty effectively. But what had happened was after EyeToy: AntiGrav sold, we had a fairly decent chunk of the studio focusing on creating other types of games and using the EyeToy as a platform. We were toying around with ideas like, “OK, maybe we should not necessarily be a music-focused studio, but a studio focused on innovation or a studio focused on creating new kinds of experiences with new hardware.”

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): But it was right at that dark moment that we got a call from RedOctane, who wanted to talk, and that was the moment that kind of changed the course of our history.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): We met Harmonix before we even published In The Groove, and were kind of known as this weird little dance pad manufacturer. But people were saying, “They’ve made high end products.” […] By that time we were in Best Buy and GameStop, and so because of that reputation, actually Sony, who was the publisher for Frequency and Amplitude, one of their producers actually called us and said, “Hey, we’re making a game with this studio. We’re making a music game, you guys might be interested in making peripherals.”

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): As it turned out, they were also big fans of Frequency and they thought, “You know what? This game would be way better with, like, a custom peripheral, arcade cabinet-type input controls rather than a game controller. Could we manufacture a custom peripheral for Frequency?”

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): We had probably one [call]. There wasn’t any sort of big ideas that popped out, but that was how we first met Harmonix, through [Sony Computer Entertainment of America] in Foster City.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): We were excited that they liked our game, but realistically the sales numbers weren’t there and it was a Sony-owned property. It wasn’t in the cards at the time. So no business actually got conducted, but we met them a bit around that time in 2002. Fast forward a couple years to the fall of 2004, and at that point they had made a strategic decision. At that point their main business, I believe, was making dance pads for people at home to play Dance Dance Revolution and In the Groove and other dance games on their home consoles. But they didn’t want to just make peripherals.

They approached us in fall of 2004 and said, “Hey guys, we’ve decided to become a game publisher, and you know, we’re sure you guys have played Guitar Freaks,” which of course we had and they had as well. And they said, “You know, if we make a guitar, would you guys make a guitar game for us?”

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): Kai ran into Alex Rigopulos somewhere—it was either GDC or either E3—after we published In The Groove, and mentioned to him we had a license. And at the time, we had floated an idea, it was very vague, of making a guitar game. We had played Guitar Freaks, we had played BeatMania, and a lot of the other games, and several people in the company had talked about making a guitar game conceptually. I think Alex responded, like, “Hey, we’re thinking of making a guitar game!”

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): After we had shipped Frequency and had been disappointed in the sales and were doing some of this dreaming about how to package that gameplay but in a form that would be easier to market, we actually started thinking about a guitar game. And in fact the name “Guitar Hero” and the concept of a guitar-based rhythm game was sort of born in that period shortly after we had shipped Frequency. I remember the meeting with Greg [LoPiccolo], actually, where he came up with that name “Guitar Hero” for the sort of Guitar-ified version of the Frequency experience that we had done.

Chris Larkin (creative services specialist, RedOctane): That was the first [developer] we reached out to, and that was really [the only one]. Because at the time really, from Western developers, there weren’t really very many people making music games. Harmonix was head and shoulders better than anybody else that was doing it at the time.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): You know, it’s funny, I remember the conversations that we had after they came to us with that basic idea. First we had, like, our adult hats on, and we were looking at all the reasons not to do it. Which includes:

Peripheral-based games were never commercially successful, at least in the U.S. Music games had never been commercially successful, at least in the U.S. So you marry one genre that’s never successful with another genre that’s never successful, it’s like, that’s not a recipe for success.

The product [was] going to be at a very high price point because of the peripheral. It was going to take a lot of space at retail which is always difficult even if you’re a big publisher. Meanwhile, RedOctane is a tiny company with very little resources, no experience with game publishing. No capital, no networks, no anything.

So you take all these reasons, and we’re just looking at it and we’re just like, “This is never going to work.” Tiny, inexperienced publisher, marriage of two unsuccessful genres, this is a terrible idea. That was the adult conversation.

And then on the other side of the ladder—fuck yeah we wanted to make a guitar game! This is the game we were born to make.

Doug Glen (director, Harmonix): Alex, with his typical humility and his thoroughness made a presentation to the board, where after identifying an opportunity to work with RedOctane said, “OK, here are the reasons why we shouldn’t do it: RedOctane has no money, they’ve got no track record as a game publisher. Frequency and Amplitude bit the dust in humiliating fashion. With the guitar peripheral, it’s a huge box and retailers hate huge boxes. Neither RedOctane nor Harmonix has the capital to build much of an inventory, so we can only ship a few and probably only ship to one retailer, maybe a few specialty boutiques. And if history is our guide, it’ll probably fail. Those are the cons.”

On the pros side, he put up onto the screen where he was presenting a picture of a blissful Albert King hitting a guitar riff that put him into total euphoria.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): I remember the board meeting actually where we were having this debate among our board about all the pros and cons and all the reasons not to do it, et cetera. And at some point one of our board members [Doug Glen] just turned to me and said, “Well, Alex, so we have to make a decision. What do you think?”

My response was, “I think we should do it because it just feels right.” And so it was not a rationally derived decision. It was an emotionally derived decision, explicitly.

Doug Glen (director, Harmonix): The board—Walter [Winshall] and Manny [Gerard] and me—in addition to being hugely entertained by Alex’s presentation, of course we supported it. But we supported it with the sort of tough love that your board is supposed to give you. “OK, you can do this, but you can do it without stopping what you’re doing to pay the utility bills, the rent, and the salaries of the staff.”

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): Because they came to us with this opportunity, because it was the exact game, the game that we felt born to make, it was easy to say yes. Despite all the reasons not to do it, it was the project we decided to throw ourselves into.

A fucking guitar controller?

Once higher-ups at Harmonix told the team about Guitar Hero, developers were split on whether or not they were excited—at least initially. However, when Dan Schmidt, the company and project’s game systems programmer, got a playable prototype up and running within the first couple weeks of development, opinions started to become unanimous. It took a little while for some, but once people actually played Guitar Hero, they were excited—even if they thought it’d be another flop.

The whole conversation started one day at lunch, when Rigopulos told his team about the company’s potential upcoming projects.

Keith Smith (quality assurance, Harmonix): We used to have these meetings, that back when it was 40-something [people working there] we could all sit in one large conference room and have lunch every Friday. We called it a “Weely” because it was supposed to be a weekly meeting but the first time a post was sent out they accidentally left out the K, so it became known as a Weely.

Matt Gilpin (lead character artist, Harmonix): I think they were going down possible things we were going to work on and I remember they brought up […] a movie [franchise], a game for a movie that was this animated movie. I don’t remember. None of us were excited about it at all. It was just like, “Oh God.”

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): You tell me if you heard this from other people, but if memory serves, he had said something like, “Hey, we got an opportunity. We can either do this […] guitar-based rock game or we could do the Disney franchise Ducktales.”

Matt Gilpin (lead character artist, Harmonix): I feel like out of the blue Guitar Hero sort of popped up. It was like, “Hey […] we’re gonna do Guitar Hero.” When they told us that we didn’t think anything of it. You were just like, “OK, what’s a Guitar Hero?”

We had done a Karaoke game, it almost seemed like a [different version of that]. Like, “We’re gonna do kind of a karaoke game but we’re gonna do it with a guitar peripheral?”

Izzy Maxwell (sound designer, Harmonix): I remember thinking, like, guitar karaoke? That sounds really dumb.

Daniel Sussman (producer, Harmonix): I love the culture and the presentation and soundtrack and all of it, but who on Earth is going to buy a game with a fucking guitar controller? This is so goofy.

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): My initial thoughts around the controller were that it was goofy and it wouldn’t work, but I was also super excited because I’d much rather work on something that has to do with rock and roll and punk rock and music than DuckTales.

Dan Schmidt (game systems programmer, Harmonix): I mean, give credit to the people at RedOctane who wanted to make this game in the first place. I think most of us at Harmonix were like, “Thank you so much for giving us money to work on this thing, but um, you know, it probably is not a very good business decision [laughs].”

Eric Brosius (audio lead, Harmonix): I wasn’t that excited about it.

Philip Winston (lead programmer, Harmonix): I think everyone was like that.

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): Until the day that we actually got a controller in our hands, and then everything changed.

Eric Malafeew (systems lead, Harmonix): I remember our team lead programmer Dan Schmidt made the first prototype. We had this beat match engine, which gave him a way to make a 2D test representation of it.

Rob Kay (lead game designer, Harmonix): It was the first milestone.I can’t remember how many milestones we had. But it was a nine month project, so it was like a month of work or [something]. It was super quick.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): Yeah, it was super fast. I mean, he’s amazing, and we also were really smart about finding the core nugget of fun in something. We didn’t ever get bogged down with all the extraneous stuff. Dan built something that was very, very—I wanna say simple. I mean, it’s simple to look at it. You know? But the emotional impact that it had on us, for something that was seemingly so simple, was just incredible. I mean, it looked simpler than Asteroids.

Dan Schmidt (game systems programmer, Harmonix): Well, we had a fair amount of music game technology already because we had been making these other games. So I was the person who went and made this first prototype. I was just trying to remember when it was and I couldn’t even tell you that. But basically I got handed a plastic guitar and some audio tracks, and you know, people said, “We want it to basically work this way. Go ahead and make it.”

I think it probably didn’t take more than, like, a week to have just something very—it was 2D. What later were gems were just little horizontal lines sliding down the screen. They were like triangles with some vertical extent. If it was a held note, you had to hold for a while. The guitar, as far as we were concerned, was basically a joystick as far as the code works. It was imitating the joystick with buttons and stuff, so I was just listening to button presses and I had some little MIDI file that I probably made myself that was the song authoring that denoted when you were supposed to hit buttons and [that] turned music on and off when your button hits were close enough to the ones in that file.

Rob Kay (lead game designer, Harmonix): It basically proved that having a guitar controller paired with beat-matching and being able to mute and unmute the guitar track was gonna connect the player to the guitar piece and make them feel like they’re playing the guitar.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): I remember the tiny—it was, like, a little 15-inch CRT television in the common area at the company where I played that first prototype. Which, amazingly, it was like, butt ugly. It was 2D, black and white graphics, coder art prototype that was already immediately fun and addictive to play, even in its hideous early prototype form.

Greg Lopiccolo (project leader, Harmonix): Which never happens, right?

Usually you work for months and months, there’s no fun, and you keep changing things and you’re looking for the fun. That was a game where it was like, the first week of development it was fun.

Chris Hartelius (character animator, Harmonix): All it was, it just counted how many notes you hit. So like, a high score would be 500 notes or something. [We had] internal competitions going to see who could get the highest score or whatever.

Matt Gilpin (lead character artist, Harmonix): I think they actually wanted to ship a version of that as an Easter Egg.

Matt Moore (artist, Harmonix): It was a really good sign that people wanted to play the game that we were working on, right? Like, you didn’t get tired of it. You might have beers on Friday and then keep playing it. That’s always a good sign.

Keith Smith (quality assurance tester, Harmonix): I told them early on that they were going to change video games, and that they were going to be huge, and they needed to stay humble. And the response I got back from [Alex] and Eran was, “If you mean sell 600 to 900 copies as changing the world forever, then yeah, we totally think you’re right.”

And I said, “You have no idea what’s coming.”

Eric Malafeew (systems lead, Harmonix): I know Alex has said this a lot, like, “We’re going to make a hundred people very happy.” [That] was his thought about the game.

Dan Schmidt (game systems programmer, Harmonix): I think it was a couple orders of magnitude more than 100.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): I think I remember having a conversation with the dev team where I basically said, like, “Well, you guys should all be really proud, this game’s great, and we’re about to make 80,000 people really happy.” And it was sort of a joke because that was the numbers that all our earlier rhythm games had sold. A little better than that. I think we had broken 100,000 units on our earlier [games], Frequency and Amplitude, but I figured, “Ehh, small publisher, higher price point, peripheral, big box, whatever.” I just did not have any illusions that the game was actually going to be a hit.

Chris Hartelius (character animator, Harmonix): That kind of just like, I dunno, it bummed me out to hear that because it didn’t make any sense to me [laughs]. I just remember hearing that, and I was just like, “That’s just crazy.” I’m glad it was wrong, because it was one of those things where I was like, “This game is awesome.”

At RedOctane things were different. Employees talk as if they knew they’d struck gold. When Harmonix sent over its first prototype, it seemed to vindicate the staff at RedOctane, indicating to them they had made the right choice.

Lennon Lange (associate producer, RedOctane): We had the first meeting with them, and they showed us a video of basically taking Amplitude but setting to rock music with some random characters that they pulled from Karaoke Revolution as mock stage characters. And yeah, so we saw that and then it was like a week later we had the Atari prototype version. And then it was just full speed ahead.

Dean Ku (vice president of business, RedOctane): Harmonix would FedEx a copy of that week’s build [throughout development]. And the first playable one, you know, we were super excited waiting for that disc, it showed up […] we all gathered around, opened it up, and started playing with it, and we’re like, “Holy shit.”

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): When they first got that very first drip of Dan’s build, I think the next day or something like that, we got a photograph of one of their producers smiling in front of that black screen, but it had a really high score number [laughs]. So that was pretty cool.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): It was a huge confidence boost for all of us. I remember it went in a very short period of time from people saying like, “Wow, this build is a lot of fun,” to people saying like, “Wow, I think we can sell a lot of units of this.”

Chris Larkin (creative services specialist, RedOctane): It was definitely kind of a high-five moment at that time. Then it kicks in that it’s real, and it’s like, “Oh man, we have to get these guitars made, like, ASAP.”

The case of the unknown song(s)

For Guitar Hero’s soundtrack, Harmonix and RedOctane would end up employing a music production company in Fremont, California called WaveGroup Sound to produce cover versions of songs they’d licensed. However, before that process got underway, to test the game, Harmonix, made up of musicians and people in bands, produced its own covers.

However, while reporting this piece, we were never able to fully nail down exactly what songs those were. A lot of people remember the earliest track in Guitar Hero being a cover of “Back In Black” by AC/DC, but others remember a whole hodgepodge of different tracks used to test the first playable versions of Guitar Hero.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): I wanna say it was AC/DC or Joan Jett. It was probably—do you already know the answer to this?

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): Oh, I can’t remember the songs.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): Yeah, boy, I dunno.

Rob Kay (lead game designer, Harmonix): “Back In Black.” AC/DC. I remember it really clearly because I don’t think we—yeah, we didn’t get it into Harmonix games until a lot later, but it was the first song that we all played on the guitar controller.

Daniel Sussman (producer, Harmonix): Eric [Brosius], our audio lead, is this wizard of music. He would just sort of go home, he had a studio in his home, and he would record stuff, soundalikes basically, that we would then level around, or design around. It was all your rock standards. I think we had “Walk This Way” and “Back In Black” and the biggest songs in rock and roll [laughs].

Izzy Maxwell (sound designer, Harmonix): Our prototype songs were “Back In Black,” by AC/DC, and we wanted to put a new song in. At the time I was really into Audioslave, I’ll own up to that, so we put an Audioslave song in there. Those were fun because Eric made the AC/DC soundalike and I made the Audioslave one, which was just cool to get paid to record a song.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): I think what we did was we made a cover version of an AC/DC song in-house, with, if I remember correctly, Jason Kendall, the singer of Megasus [the band Lesser is in other former Harmonix employees Jason Kendall, Paul Lyons, and Brian Gibson], singing the parts. God, I can’t remember. Maybe it was “Highway to Hell,” or something by AC/DC.

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): We had to do covers ourselves, so we just went ahead and formed a band and did “Back In Black,” and I think we did “Sweet Emotion” from Aerosmith. And “Back in Black” is from AC/DC. So of course they had me sing it, right? So I did my best Brian Johnson. It was annoying to hear my voice coming out of every single monitor every day for a while while you’re trying to get the animations correct [laughs].

Greg LoPiccolo (project leader, Harmonix): Brosius went home and banged out, I think it was “Walk This Way.” He just covered “Walk This Way,” played all the parts, he programmed the drums, came back with a backing track and the guitar part for “Walk This Way.”

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): “Walk This Way!” That’s what it was. It wasn’t “Sweet Emotion,” it was “Walk This Way.” Sorry.

Lennon Lange (associate producer, RedOctane): I think it was a Weezer song.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): I still remember pretty vividly—the first build was basically a black screen and three colored dots coming down and it was set to a Weezer song. A Weezer song called “Dope Nose.” That was it. One song.

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): I don’t know about “Dope Nose.” I mean, I obviously know the song, right? But I know for a fact that Eric Brosius, I, and a few other people put the songs together for “Walk This Way” and for “Back In Black,” and those were the first two that we, like, really started hammering on.

[Weezer’s “Dope Nose” was featured in Amplitude, so it stands to reason this might have been the song mentioned in Harmonix’s initial pitch video. We can’t say for sure, though.]

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): I guess it would make for a better story if we knew what the song was.

Short on time, short on money

The deal between Harmonix and RedOctane to develop Guitar Hero was sealed around late 2004, early 2005. But it came with a caveat: In just approximately nine months, Harmonix had to be ready to ship this new game; RedOctane wanted it on store shelves for the 2005 holiday season. Not only that, Harmonix had to do it for less than $2 million—a tiny budget for a video game, even at the time.

According to the people who worked on the game, these constraints largely benefited the project. There was no time to meander on extra ideas, mechanics, or features. So the team only worked on what it deemed absolutely essential to the Guitar Hero experience.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): The budget for Guitar Hero 1 ended up being, I think, $1.75 million, which at the time was a huge risk for us.

Dean Ku (vice president of marketing, RedOctane): I remember afterwards talking to people—it was just unheard of in the industry.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): The year we had released In The Groove, even at that time we had only done a total of a little over $9 million in sales. Not even profits, that was our sales, and we’re taking on this gigantic financial risk [with Guitar Hero]. At the same time, $1.75 million I think for Harmonix was smaller than their other budgets.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): It just so happened that they reached out to us in fall of 2004, and they wanted to ship the game for holiday like every publisher does—or at least in that era. I mean, now with digital releases, holiday is less critical than it was in that time. But in that time, it was all about the holiday. Particularly for a game like this, that is a perfect Christmas present. They had to be on shelves for holiday.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): It was either gonna ship Christmas 2005 or Christmas 2006. 2006 was way far from where we both wanted to ship, so we sort of planted the flags and shrunk the project down to where we thought it was shippable in 2005.

The original concept, people were talking about online versions, online modes, and there was a whole bunch of other things that we just decided in the end, “Alright, none of this would allow us to ship in 2005.”

And honestly, another limitation of that development schedule was just financially for both sides, we kind of needed the game to do well and to ship.

Chris Larkin (creative services specialist, RedOctane): I think if Guitar Hero had been a failure, we probably would’ve closed our company. We were still doing dance pads and things like that, but sales on that were starting to come down. That’s why we were trying to find the next big thing. So yeah, it really was, for us it was kind of a make it or break it.

Charles Huang (co-founder and vice president of business, RedOctane): It’s kind of funny as I think back to it how much of it was sort of this great big creative vision being whittled down by the financial challenges, the technical challenges down to, like, “Alright, this little product is manageable for us.”

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): We loved the fact that they were basically betting the farm on this project.

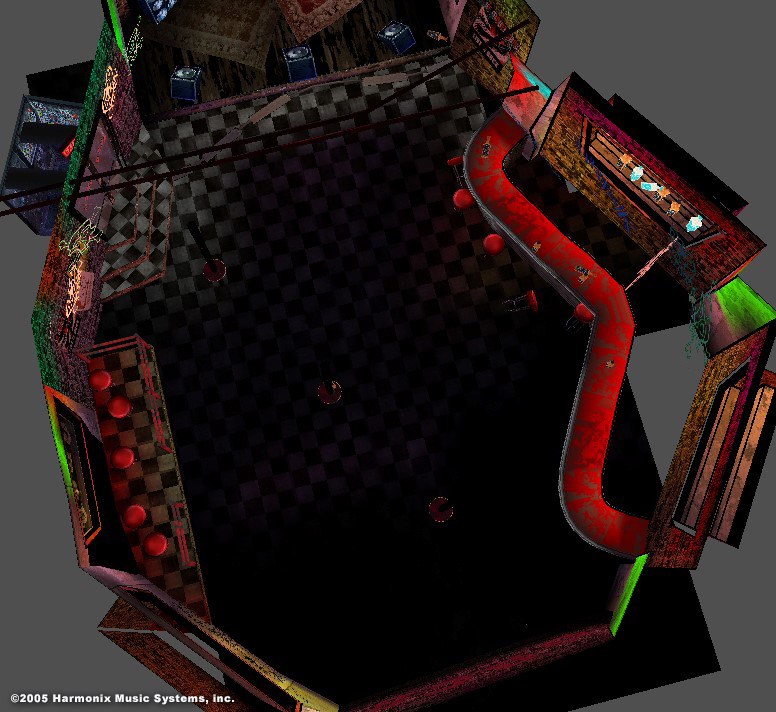

Chris Hartelius (character animator, Harmonix): The scope, however handful of venues that went in, the six to eight characters that went in, it’s all related to that timeframe. It’s built around scheduling to make sure we can fit it in. Not only is it motivation to finish it in that timeframe, but it’s also built so that it’s not going to have hundreds of characters or hundreds of venues that we can’t actually finish in time.

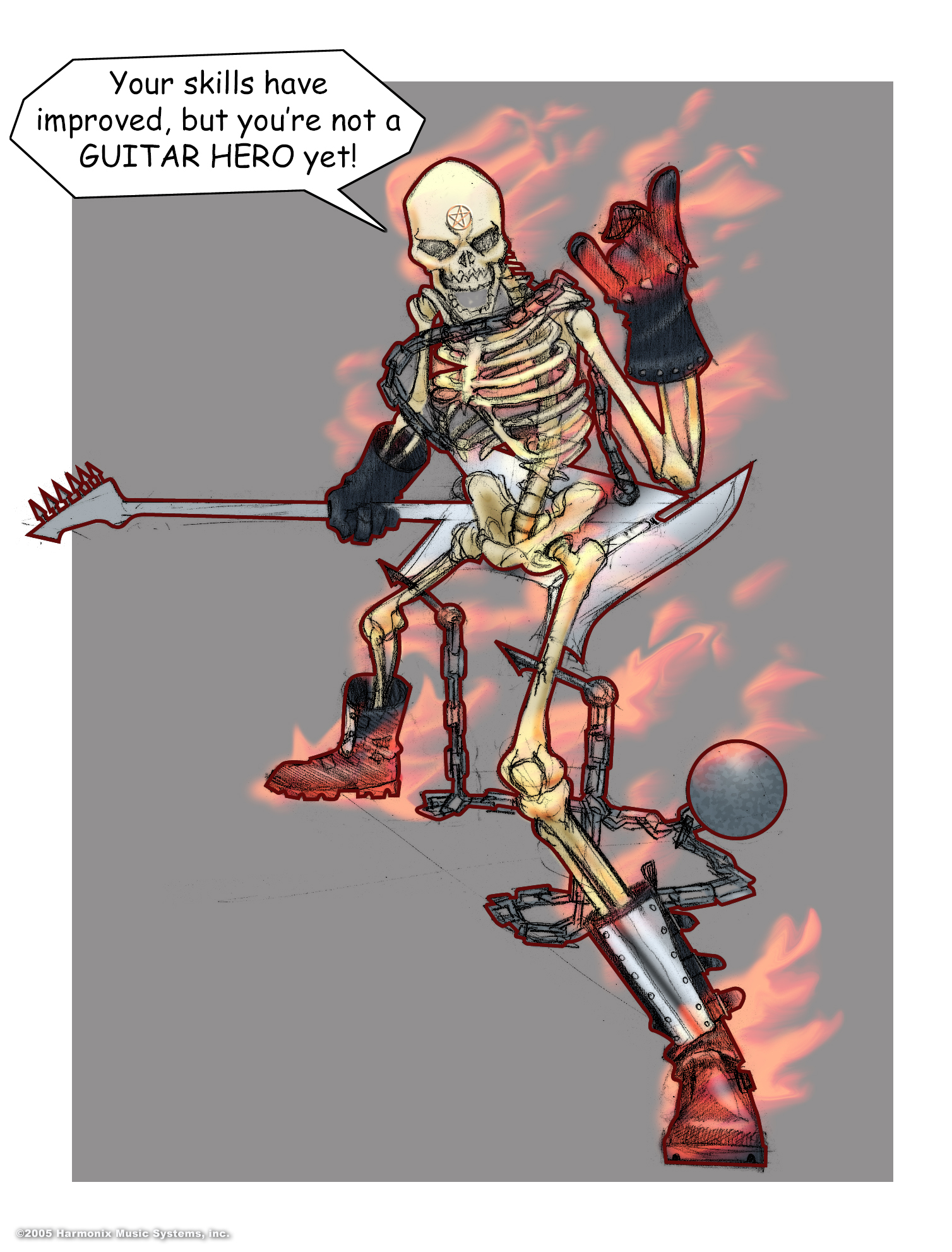

Rob Kay (lead game designer, Harmonix): That’s why the newspaper reviews came out. I remember being inspired by The Incredibles. They had a scene in The Incredibles where the hero’s looking at his walls of all the newspaper cuttings of his life. It’s like, “Oh, we could have newspapers!” That’s a very cheap way to tell a story. You kind of show a newspaper cutting, and it could be the review of the show.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): For example, go back and look at the drummer animations in Guitar Hero 1. It’s comically awful. Compared to, like, by the time we were making Rock Band, for example, we had this incredibly sophisticated animation system that made the drummer play every note in the drum part sort of drum perfect. And the guitarist, their left hand is in the correct fret positions on the neck of the guitar. And the animation—it’s all this sophisticated stuff. Rewind to Guitar Hero 1, and it was just like butt simple, barely functioning animation [for] the other musicians on stage because, again, limited time, limited money. We had to.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): It’s hard to imagine making that game right now with that amount of money, but I think because it was a scrappy little company and it was just sort of the right time […] a lot of the decisions in that game did not have to be difficult ones, because we all were like-minded and knew what we wanted to make. I think that helped us make such an influential game with such a short amount of time and money.

PART 2: THE RIGHT PEOPLE FOR THE JOB

Under the hood

In game development, making a new series, or intellectual property (IP), is notoriously difficult. The game industry thrives on sequels, which are able to iterate on the ideas of an established brand, building on something that’s a known quantity. It keeps a developer from having to start from scratch every single project.

But Harmonix also had a solid foundation it could build on top of: its previous games.

Even though it had made Frequency and Amplitude for Sony, and had developed the Karaoke Revolution series for Konami, Harmonix, an independent developer, was able to retain a lot of the under the hood technology it’d used in previous games on Guitar Hero. It also, of course, had a lot of music game development experience at this point. So even though Guitar Hero wasn’t a sequel to Frequency, Amplitude, or Karaoke Revolution, and despite the fact that it was published by a different publisher, it was able to build upon all the lessons the team had learned and the tech they’d built up to that point.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): [O]ne of the advantages we had at Harmonix is that we basically owned our own code. The technology that we developed from our first game, which was Frequency, and then all the way up through all of the games, we had an internal engine that we used. Which means that a subsequent game that we made would be able to take advantage of innovations that we had created.

Eric Malafeew (systems lead, Harmonix): But we also had just proprietary everything else—the tools, the graphics, the rendering. Back in the day, we didn’t have Unity or Unreal; [they] weren’t as accessible or powerful as they are now. In later days, in the past five years, Harmonix has moved to those things and carried their core audio engine over to those, but back then we just made everything from scratch.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): I don’t know specifically what it’s like in other studios, but I do know that we made it a point to have clear distinction about what Harmonix owned and what the publisher owned. And in general, our deals were structured such that the publisher owned what’s known as the “look and feel.” Essentially, the graphical assets and what the game looks like. Whereas the underlying technology—the code, or what we call the engine—was always something that Harmonix retained ownership of.

Greg LoPiccolo (project lead, Harmonix): Basically, we had developed a whole beat match library and a set of design insights from Frequency and Amplitude, and then we figured out all the character animation and crowd and cameras and venue rendering in the Konami games, in the Karaoke Revolution games. When Guitar Hero showed up, it was like, “Oh OK, we have all the stuff we need!”

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): Guitar Hero was the first game where we were able to merge the kind of fiendishly addictive rhythm gameplay from our early games, Frequency and Amplitude, with the very superficial marketability of the Karaoke [Revolution] games, where one screenshot and a sentence or two and you just know what this thing is.

Kasson Crooker (audio director, Harmonix): If Guitar Hero was Harmonix’s first video game, first music video game, it probably would not have been that good. […] It wasn’t until Karaoke Revolution where you put a mic in somebody’s hand and you say “It’s karaoke, just sing,” they know what to do, and suddenly the barrier is broken and people get into it. That was a huge lesson learned for Guitar Hero, which is, if you’re going to do a guitar game it has to be like karaoke.

Rob Kay (lead game designer, Harmonix): I think that was a massive part of Guitar Hero’s appeal; you could see somebody playing it and you instantly understood the fantasy and what you would get to do in the game. You’re like, “Oh, I get to be a guitar god because I can see that I’m going to be holding this guitar and making those kind of motions.”

Freaks

There was another unique advantage Harmonix had when working on Guitar Hero: it was a studio full of musicians and people in bands. In fact, for a long time, it was almost a non-official prerequisite for working at the company. Speaking to people for this project, it was rare to hear anyone say they weren’t a musician in some capacity.

Similar to its mission statement of wanting to bring the joy of music making to everybody, with Guitar Hero, Harmonix wanted to give players the unique experience of playing music on stage in front of an audience. Of being, well, a “guitar hero.” To do that, Harmonix would look to one key place for inspiration: itself. Guitar Hero was inspired by the real-world experiences its employees had of playing in and touring with bands.

With the people making the game so ingrained in the culture it was trying to imitate, every facet of Guitar Hero was meant to be an homage to rock and roll, to do the genre justice. The game is full of references to developers’ own experiences playing music and nods to musicians and people they were fans of. According to the people we talked to, if Guitar Hero wasn’t made from a place of authority, at the very least it was made from a place of sincerity.

Dan Schmidt (game systems programmer, Harmonix): Oh, completely, yes. Take that sentence you just said and pretend I said it to put it in the oral history. We definitely felt like we were the people to be making this game. This was a company of rock musicians, basically, and I think that’s one reason that it turned out so well.

Daneil Sussman (producer, Harmonix): We had enough people who’d experienced [the band life], had been on the road in their own bands, had slept in vans, and had shitty practice spaces, and had guitars of their own. There was a really strong affinity for the culture, but not to a person. And then we had people who were like, “Guys, I don’t know what the fuck a whammy bar is. Like, what are you talking about?” So you know, there were people that kept us in check from getting too deep down the rabbit hole.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): Music made its way into everything in our corporate culture. If you stuck around for five years, you got, among other things, a reward of $500 to spend on music gear. People loved it at Harmonix so much that we had to invent a 10 year one, because we were having all these 10 year anniversaries, so we gave $1,000 to go buy music gear. And then 15, I got my 15 year one, and so on. Little things like that made their way into every little nook and cranny of the company.

Probably to the detriment of the company as the years went on, because I have heard, now that I work with other studios, I’ve heard people complain that they never even applied to Harmonix because they had to be a musician. In some ways, that may have even hurt us in ways we’ll never know. But at least in the early days, it was nice to know that if you started talking about some random Fleetwood Mac b-side, almost everyone would know what you were talking about.

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): We were all freaks.

Matt Moore (artist, Harmonix): There was a venue right down the street called T.T.’s, T.T. the Bear’s. That was awesome in that it was just a few blocks away from the office, but oftentimes somebody would post into general chat or send out an email or something and say, like, “Hey, my band’s playing down at T.T.’s,” or some other venue, “Please come.” Whenever you’d go, there’d be many faces you knew from work who were also going to the show.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): Harmonix did create bands. People at Harmonix would join together and make bands. Either experienced [people], like Megasus, we made that band while we were all working at Harmonix, [or] bands would be born out of new players that are starting to get better because they’re surrounded by music all the time and kinda growing into a band themselves.

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): And we had a practice space, too. We all got together and we actually used Outlook to schedule practices for bands down there.

Daniel Sussman (producer, Harmonix): You look at the writing and there’s a lot of inside jokes—the basement address is Greg’s practice space studio. You know, it’s like we were all pulling from the life experience that we’d lived. For a lot of us, it was really that cool that anybody gave a shit. It was like, my life has [been] validated in some weird way.

Greg LoPiccolo (project leader, Harmonix): We loved it. We were into it. And we very much had that sense of like, “Let’s try and introduce people to the things about rock and roll that we love.” You know? It was a lot of inside jokes, like the loading screen tips, and details about stuff on stage. We would try and jam as many inside jokes and rock references as we could into it.

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): We realized, like, “Hey, for loading screens, we want to have tips. But we don’t want to have just Guitar Hero tips, we wanna have real tips [for] if you’re actually touring in bands or if you’re playing shows. We need to gather actual tips.” An email chain went out like, hey, add your tips in, send them in.

I sent a bunch, I remember a couple of my tips got chosen, but the one that got chosen for the loading screen that I’m always proud of because I think it’s hilarious and true is just this—”Always keep an empty bottle in the van. You’ll see [laughs].”

Dinner Horse

The influence of Harmonix’s music history is also reflected in one of the most visible facets of Guitar Hero: its art and presentation.

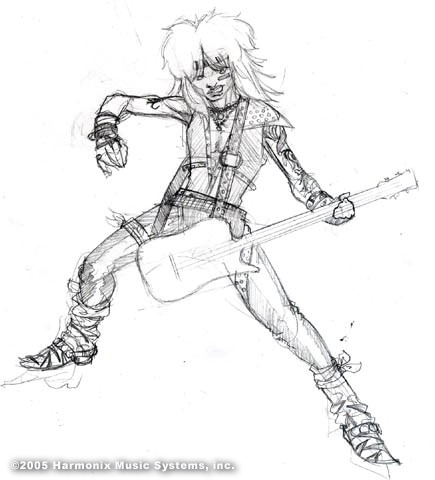

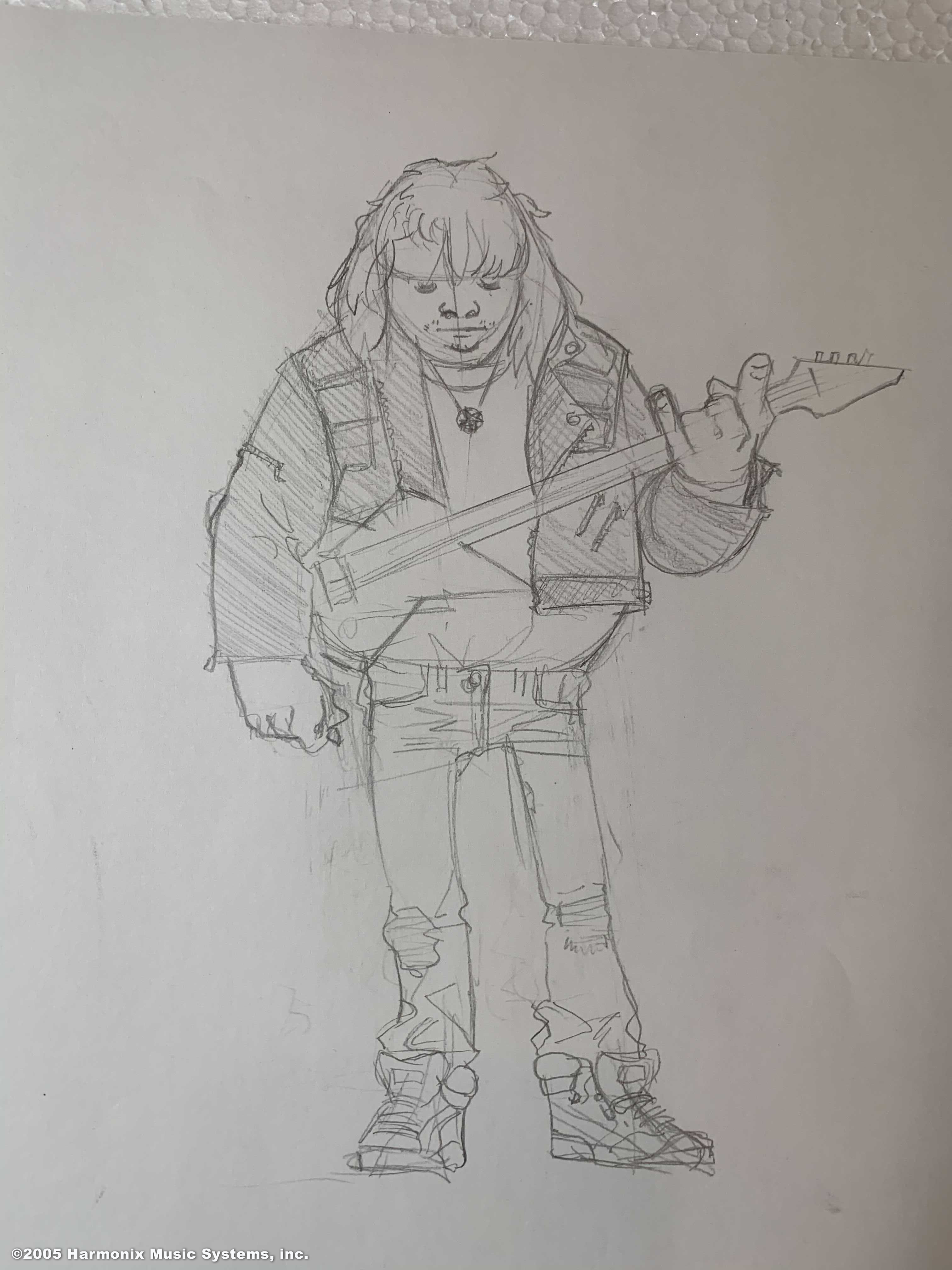

Led by Ryan Lesser, the small team, made up of a lot of people Lesser hired from the Rhode Island School of Design, where he also taught, was in charge of getting the characters, venues, guitars, and all art across the board into the game. But the team didn’t have to look far for inspiration for things like characters. Sometimes they just needed to look a desk or two away. Sometimes they needed only look in the mirror.

Eric Malafeew (systems lead, Harmonix): You know, [the Guitar Hero] team was so heavily influenced, I would say, by the art staff. It wasn’t a lot of this new code being written. Ryan Lesser, our art lead, was coming from Providence [Rhode Island, about an hour from Boston], like a lot of our artists did, and he was also into the music scene down there quite a bit.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): The cool thing was that most of the art team were rock artists—rock musicians—so they also grew up with the same things. We could have meetings where we were talking about all these references and they just totally got it. If we said, “This is going to be our CBGBs,” everyone there knew about it because we had played there or we had seen shows there.

Chris Hartelius (character animator, Harmonix): It was just like six of us [on the art team] in this not super small room, but we were all pretty close together.

Matt Moore (artist, Harmonix): It was a really tight crew. It was great, everybody was sitting next to each other. I think it was a really great environment for just giving each other lots of feedback; people could just sort of bounce around and bounce ideas off each other. It was easy to stay aligned on art style because we were all so close.

Chris Harterlius (character animator, Harmonix): I did talk to Matt Gilpin prior to this, and he reminded me that they gave me my nickname, which is “Horse.” [laughs]

Matt Gilpin (lead character artist, Harmonix): He was playing [World of Warcraft] and another guy, [artist] Scott Sinclaire, was also playing, and Chris named his character “Dinner Horse.” Chris has a good sense of humor, so he just made this crazy name. His character’s called Dinner Horse. He just slowly started becoming referred to as Horse. And to this day he’s Horse. I don’t ever call him by his real name [laughs].

Chris Hartelius (character animator, Harmonix): Over a short amount of time, that nickname just kind of expanded beyond the art pit to the upper managers and the CEO calling me “Horse.” They’d call me Horse in a meeting. It just made me laugh every time, just the fact that they were shouting Horse, and just saying, “Horse do this.” Or, “Horse can do that!” It was just very entertaining for me and pretty cool to see how everyone was comfortable just calling me that and that it went beyond the art room. I still have that nickname today.

I mean, a lot of people don’t actually know my real name at the company [laughs].

Matt Moore (artist, Harmonix): Yeah, that actually was a problem on Slack when it got implemented. People didn’t know how to contact him because Horse wasn’t in the directory.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): I would say I had two main influences for [Guitar Hero’s art] style. One was I’ve always been a poster artist, like silk screen posters for rock bands and metal bands and stuff like that. So I wanted to bring in the gig poster vibe, which at the time was really getting hot again. It died out for a couple decades and then was really picking up back in the days when GigPoster.com was still alive and all the first wave, second wave gig poster artists were making their stuff. I wanted to bring that to the game, I thought it was really unique and didn’t look like every other game out there, and was really related to rock and roll in a way that was atypical.

Matt Moore (artist, Harmonix): We had a shared art forum where we would keep tons of reference imagery. You know, there’d be rock posters from hundreds of different bands, and thousands of different shows, and we’d sort of be collecting references that way.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): I called my friend Shepard Fairy [founder of OBEY Clothing and designer of the Barack Obama “Hope” poster] and he put some posters in. And we called Tara McPhereson and Brian Ralph and a bunch of other people. So there are actual rock posters in those games in the shell. If you’re in the menu system for Guitar Hero, it’s all rock posters.

Matt Moore (artist, Harmonix): The art style, pretty early, I think we decided to set up the menu system to be inspired by rock posters—and there was just so much fun and varied art style[s] to work with there. A lot of that was influential in the characters and environment as well.

Ryan Lesser (art directory, Harmonix): And then the second influence was similar but a little bit earlier. It was the general feeling that I got being a metalhead in high school in the 80s. The kind of meat-headed, macho, but big heart that 80s heavy metal had. The way I transformed that pseudo-machismo into the game was [with] big, top-heavy shapes and really thick or really thin extremes, and all the rooms, we called them the clubs, basically our levels, they were all kind of off kilter and wonky. Nothing was plum, nothing was square, everything would be on an angle, kind of swollen and top-heavy, and looked like it was sort of falling over. [It was] stylized almost like Edwards Scissorhands in a way.

Matt Gilpin (lead character artist, Harmonix): Actually we called the art “wonky,” that was the term we would use. Like, you know, a speaker or an amp wouldn’t be squared off. One side would be a little more tilted and curved. So we always called it “wonkifying.” The guitars we tried to do that with, but they’re such a weird shape to begin with that whatever you did didn’t work. I think the only place we could sort of wonkify it was the headstock.

Greg LoPiccolo (project leader, Harmonix): Ryan Lesser had a very specific idea of what he thought it should look like. Which I, quite frankly, didn’t totally understand. I was a little skeptical. But I was like, “He’s smart,” and I was like, “OK, Ryan. Go do your thing.” And he killed it. He was totally right.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): Not everyone was on board with that kind of weird art style. They didn’t think it was palatable. They didn’t think it would be as pop as it needed to be. But I felt really good about it, and being a huge rock fan, I just really felt like it spoke to the style of the music. In the end, when we were done and we released it, those folks came up and they were like, “You were right [laughs]. I was wrong, I’m sorry.” Which happened a lot! You know, we were a good group and we didn’t hold grudges. When people were right or wrong, it was not a big deal to be like, “Yep, you had it.”

Another influence from my rock years in the game was the character designs. Those are based on people that we knew growing up, or even as adults in the rock scene. So like, Axel [Steel] just was basically me in high school.

Matt Gilpin (lead character artist, Harmonix): Axel Steel definitely started from just both Ryan and I, the era we grew up in. There was a lot of kids into Megadeth and Anthrax. I was young enough that those were kind of older kids, and they would scare the shit out of you and threaten to beat you up all the time [laughs]. For me, that was what he was. When we designed him, we were both pretty much on the same page with that guy. He had a couple variations where we just were trying a few things, but you know, he settled on what he looks like based on [our past with] kids who were really big fans of those bands.

Matt Moore (artist, Harmonix): Actually, there was this terrible incident where during the concept phase I had unknowingly included an icon that was, like, controversial and I hadn’t known the meaning of it. […]

It was, like, a rightwing, nationalist—it was not a Nazi thing. But it was, I dunno, similar to a shape on a—it was a white supremacist kind of thing. Yeah, it was not good. It actually made it onto the guy, onto Axel’s teeshirt, and then someone in QA was like, “Woah! This needs to change!” It was embarrassing.

Matt Gilpin (lead character artist, Harmonix): I know Axel Steel started out as—this is the one I was like, “This name is not great”—[he] was going to be Hair Matheson. We worked with actually a really good guy named Dare Matheson, and I was just like, “That’s a little too on the nose and too goofy.”

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): Judy Nails, interestingly enough, was based on Judita Wignall who was a musician and in bands that we wound up hiring to be a mocap actor for the game because we really like her and everything she did on stage and stuff. I wound up reverse engineering that and putting her right into the game as Judy Nails.

Jason Kendall (artist and animator, Harmonix): So I’m actually Eddie Knox. Eddie Knox was based off of me. I don’t know if you know who Eddie Knox was, he’s like the rockabilly-ish guy. […] [He] was originally called “King Kendall,” which is actually my name in [my band] The Amazing Royal Crowns if you look on Wikipedia.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): Pandora was loosely based on [D’arcy Wretzky]. I really loved the bassist from Smashing Pumpkins.

Matt Gilpin (lead character artist, Harmonix): Izzy Sparks was—there is a guy we worked with named Izzy. That’s not a very common name and it fit the character.

Izzy Maxwell (sound designer, Harmonix): There was one day in particular that I came in, and I was tired and not a hundred percent with it, and I walked by the meeting room and I hear everyone’s talking about me. They’re saying like, “Yeah, Izzy doesn’t look that good. He’s kind of emaciated, his face looks all messed up.” And I’m freaking out thinking, “What are all the managers, like, doing in the office talking about me and how I look?” And you know, eventually I put it together, but it was a fun morning [laughs].

The controller

On top of developing the actual game portion of Guitar Hero, Harmonix had to design what would become the selling point of the title—the physical guitar it’d ship with. While RedOctane would be responsible for manufacturing the hardware for the peripheral, it was up to Harmonix to figure out just how this thing would work in tandem with gameplay.

Alex Rigopulos (co-founder and CEO, Harmonix): Well, you know, a lot of the earlier conversation [was] about all of the ways that we wanted it to be different from Guitar Freaks, actually. We wanted to break away, for example, from the 2D UI that characterized so many of those early games in Japan. We wanted to break away from the three button constraint [that Guitar Freaks had] that felt very, just too confining and [limiting].

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): We also really wanted to try and give people the feeling of playing a real guitar. It was important to us when we started designing the hardware, the very first sketch that I did for that SG [model of Gibson Guitars that the controller was based on]—which started as that because that was my guitar at the time, I was a Gibson SG fan for a long time—[to think about,] “What would the buttons be like?”

Rob Kay (lead game designer, Harmonix): I remember after one of the early meetings we had, where we were talking about the guitar controller and how many buttons it should have, Ryan was quite excited about the idea that if we had five buttons on the controller we could get three power chord positions that players could play with their fingers.

Eran Egozy (co-founder and CTO, Harmonix): You might think that’s strange because, you know, really you can only use four fingers to essentially fret the guitar, but adding that fifth button actually was really important, I think, because it made for more interesting gameplay. You actually had to think about shifting your hand to be able to play the faster passages, which made for a better game.

Ryan Lesser (art director, Harmonix): That was important in two ways. One is that it created an extra challenge for people, especially if you were not a guitar player, and two, it simulated the feeling of playing guitar. Let’s say you’re even in a simple punk rock band, you’re going to be banging out power chords. It’s the same chord position on your left hand, so there’s not a lot that changes there, but the way you move it around on [the] neck of your guitar changes everything. It’s where all the magic is. So being able to give the players now multiple positions made them feel more like a guitar player, rather than playing like, a simple video game interface.