Humanity’s first adventures in space were catalyzed by intense competition between two rival nations. But in the wake of the Apollo Moon landings, the United States and the Soviet Union both backed off, and began favoring policies of détente, or an easing of tensions, on and off Earth.

One of the most fascinating byproducts of this geopolitical shift was the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), the first collaborative space mission between these two initial space powers, or any nations for that matter. The mission objective was to dock the American Apollo command/service module with the Soviet Soyuz capsule in orbit, allowing two Soviet cosmonauts and three American astronauts to share a multinational orbital habitat, built from the most iconic spacecraft of their respective nations.

Videos by VICE

It all went down 41 years ago Sunday, on July 17, 1975. Both vehicles had been launched within seven hours of each other on July 15, and had spent the previous two days meandering over to the meetup point, about 140 miles over continental Europe.

The American module was the last Apollo vehicle to fly in space, and was commanded by Thomas Stafford, who had served on Apollo 10 as well as two Gemini missions. Stafford’s two crewmates, command module pilot Vance Brand and docking module pilot Donald “Deke” Slayton, had never been to space before, though Slayton was one of the famed Mercury Seven—NASA’s first group of astronaut candidates.

THE ASTP crew. Image: NASA/Adam Cuerden

The Soviet side was commanded by cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, the first person ever to conduct a spacewalk (and an awesome space artist to boot), and Valeri Kubasov who had flown once before on Soyuz 6.

The event was covered live by ABC News and other networks, using footage from a camera on the docking side of the Apollo module.

ABC newscast on ASTP docking, July 17, 1975. Video: Dan Beaumont Space Museum/YouTube

The two capsules, each moving about 17,300 miles per hour, carefully approached each other as the world looked on. “Apollo is ready,” Stafford said to Leonov in Russian. “I’m approaching Soyuz.” (Fun fact: Leonov joked that Stafford’s heavily accented Russian was a separate language he called “Oklahomski”).

At 12:12 PM EDT, the Apollo and Soyuz docked successfully, “Apollo and Soyuz are shaking hands now,” Leonov said.

A few hours later, after the spacecraft had been secured, Stafford and Leonov followed the example set by their vessels by shaking hands through the Soyuz hatch.

Stafford and Leonov shake hands. Image: NASA

The gesture was viewed as a historic act of friendship between rivals, and “a political as well as scientific miracle,” according to a New York Times article titled “Beyond Soyuz-Apollo,” dated July 20, 1975.

“Perhaps from the perspective of the year 2000, it will seem equally incredible that as late as 1975 there could still be doubts about the prospects for large‐scale international cooperation in space,” the article said.

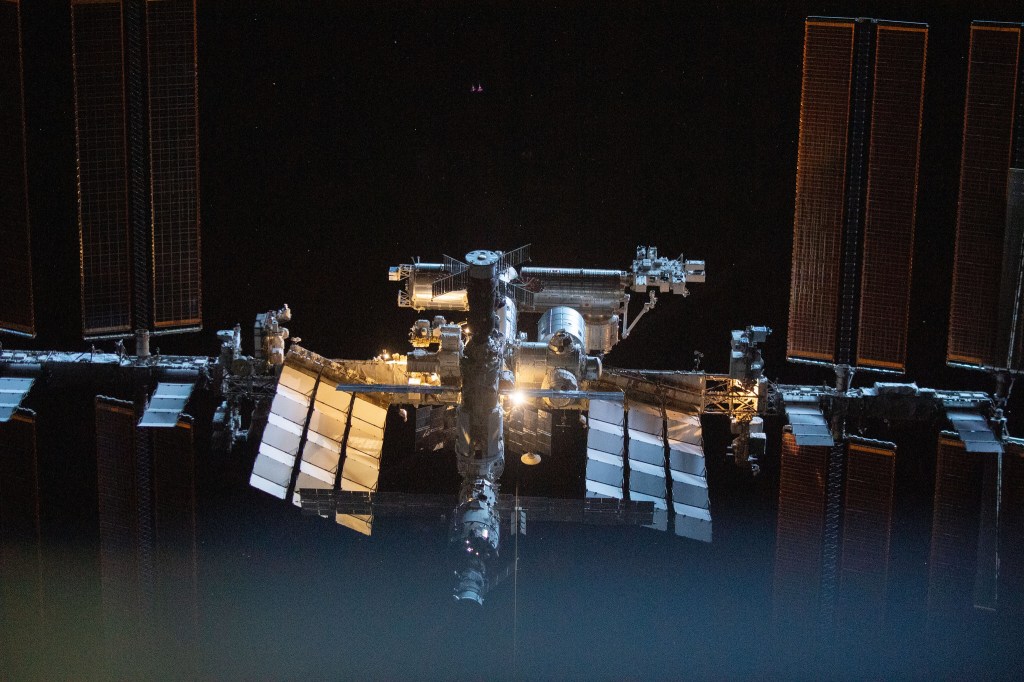

Now that we are well past the year 2000, it seems incredible in retrospect that as early as 1975, such substantive collaborative efforts were successfully made, not to mention that geopolitical challenges still raise doubts about space collaboration today. That’s why it is encouraging to celebrate the success and legacy of programs like ASTP, which not only laid the practical bedrock for mega-projects like the International Space Station, but also acted as a powerful symbolic gesture of global cooperation in space.