“Does anyone know what to do re: delivering the Murri girl’s letter to the Moreton Bay Courier in Brisbane?”

It’s a fairly innocuous forum post, someone looking for a bit of help or guidance in a possible encounter in the mobile game 80 Days. But it utterly delighted Meg Jayanth, who wrote the game.

Videos by VICE

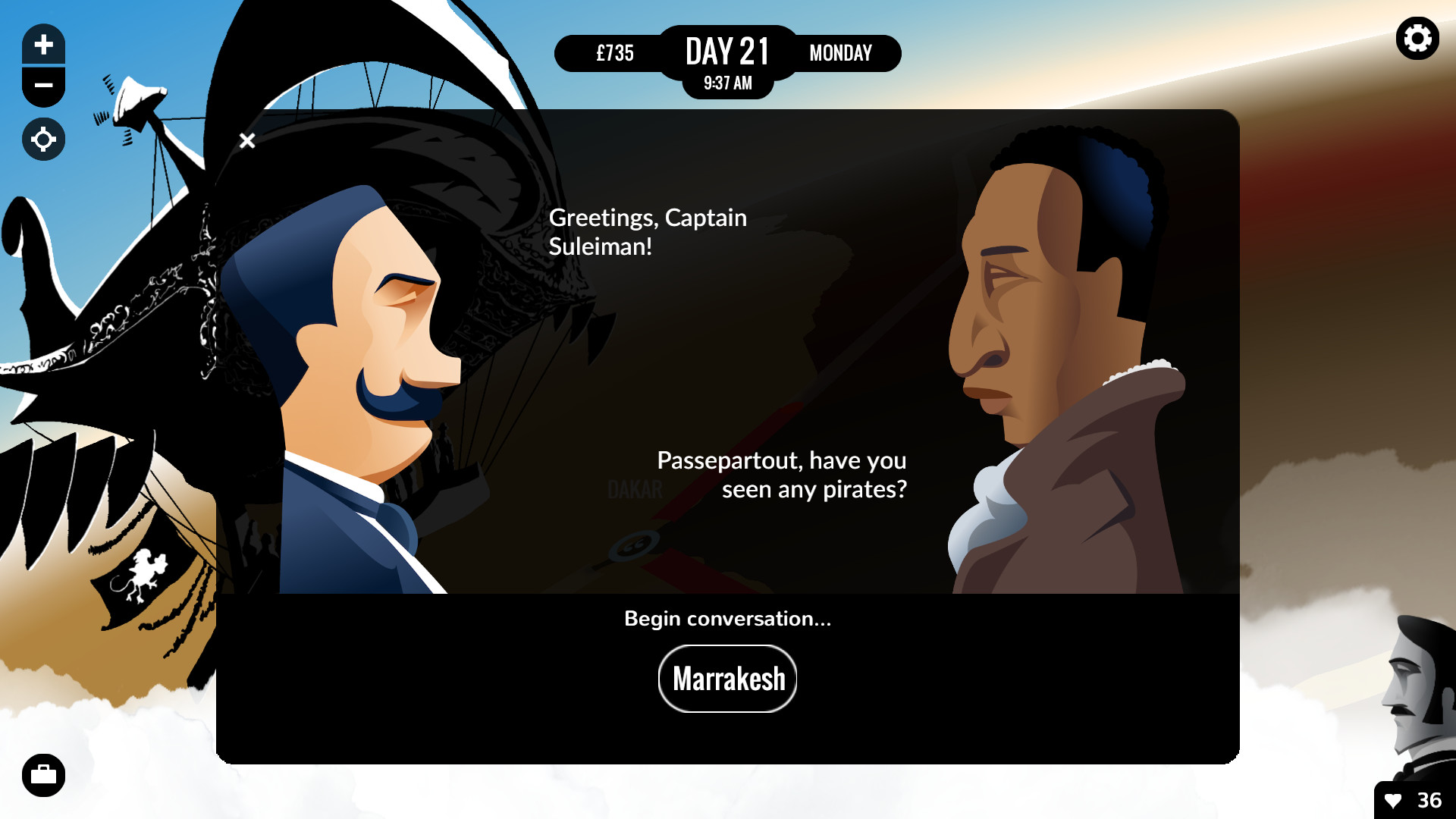

In Inkle Studios’ 2014 game 80 Days, one is tasked with the Vernian feat of traveling around the world in the eponymous number days. The world you traverse in the game, however, little resembles Jules Verne’s late 19th century adventure. His Around the World in Eighty Days celebrates the daring travels of two well-to-do white men (one English and one French) through Indian colonies and encounters with strange foreigners. Jayanth’s reimagining, however, is a purposefully anticolonial adaptation in an alternative history. With a side of steampunk. And flying monsters.

“In 80 Days we use the steampunk and the fantasy to enable us to tell the kind of story we wanted to be able to tell to redress some of the colonialism and sexism and racism of the period,” Jayanth said in a talk at GDC in 2016. “If you’re going to invent a world, why not make it more progressive? Why not have women invent half the technologies, and pilot half the airships?”

There’s a growing movement within the games industry to tell these kinds of stories, to examine familiar stories and narratives from the point of view of the marginalized people who were so often reduced to stereotypes or ignored entirely. But while developers are increasingly committed to this work, the industry as a whole is still largely male and white. There are few women or people of color in leadership positions, as Jayanth was with 80 Days, who have the background and point of view to handle these stories well. And— too often—it shows, as attempts to be sensitive and aware ricochet into new forms of white / western savior narratives. It takes a lot of forethought to avoid those traps, as Jayanth’s experience shows.

Beyond informed and diverse representation, Jayanth wanted to ensure that players felt the weight of their own character Jean Passepartout’s western whiteness and maleness. Which comes back to the Murri girl in Brisbane.

80 Days screenshot courtesy Inkle

At a point in your travels, you may encounter an indigenous Australian girl of a Murri tribe. The player can engage her in conversation, and she tells them of the suffering her people have faced at the hands of white colonials. She’s written a letter, and is trying to get it published in the local newspaper to address her complaints.

The player can offer to help her, to “use your whiteness and maleness and position as protagonist ,” to deliver the letter for her. She will not let you. Explained Jayanth, “She does not trust you because you are an outsider, you are white, you are male — you are closer to the oppressor than you are to her, and all the good intentions in the world can’t change that.”

And so exist the forum debates. What items were you carrying? Did you side with the revolutionaries? Which dialogue combinations did you choose? And you still couldn’t deliver the letter?

“‘Solving it’ using Passepartout’s white privilege, actually would just make the solution part of the problem,” Jayanth says. “Passepartout cannot ride to her rescue, cannot solve racism by posting a single letter. And the protagonist cannot get past years of ingrained distrust of whiteness and his ignorance of local culture and politics in the course of one conversation — she is never going to open up to Passepartout no matter what item you — the player — try and use from your travels.”

After repeated attempts, a user posts: “Maybe it’s a life lesson: sometimes, no matter what you do to try to help, bad things will happen.”

“Exactly!” Jayanth says. “This is not a bug; this is the entire point of the game.”

In the time since 80 Days‘ release, more games have tried to have more pointed discussions involving race, gender, and inequality. These tensions are often obfuscated by more fantastical elements. “Sometimes it feels like we’re trying so hard as an industry not to see the elephant in the room that we’ve actually invented a whole herd of magical dragons over there,” Jayanth says. “Can we please talk about the elephant? It’s still here. We are still here and we deserve our lives to be represented as more than just a metaphor.”

The protagonist cannot get past years of ingrained distrust of whiteness and his ignorance of local culture and politics in the course of one conversation…

And sometimes games simply end up repeating real-world crimes and exploitation via those magical dragons. It was distressing to play through Mass Effect: Andromeda‘s oblivious relationship to colonialism. Humans serve as a player-surrogate, settling on planets and killing their hostile native population in droves. When listening to an early game audiolog left behind by the alien Kett, Ryder even remarks to the effect that she “doesn’t need to understand the language to understand a monster.”

This doesn’t even begin to address the way the Mass Effect games have historically treated relations between other alien races, and their thinly-veiled real-world analogues. The forcible sterilization of the “warmongering, savage Krogan”, for example, is rarely given the long-lasting weight that it deserves. In the final instalment of the series, Shepard is forced to walk through a Krogan laboratory where attempts to cure and study the Genophage has resulted in the death of countess women. Thousands of years of conflict are used to fuel a hero narrative for the player, with the illusion of a choice. According to BioWare, 92% of players cure the Genophage, giving themselves a pat on the back for doing the right thing when an alternative was presented. Who wouldn’t cure the forced sterilization of an entire species?

In Mass Effect‘s attempt to have this conversation, it feels ignorant of the very real—and very recent—colonial history of forced sterilization in the name of cultural protection. According to a study at UC Santa Barbara, approximately 20,000 cases of unwanted sterilization occurred in the state of California alone— up until 1979. To have these discussions in a video game is difficult. But if a game begins this conversation, it must strive to be responsible, and it must listen to all voices. The guise of the fantasy metaphor can be self-serving: keeping players distant enough to discuss these issues in a way that feels productive or responsible, while still being able to declare that it’s just fiction should anyone take issue with the subject’s presentation.

Mass Effect 2 screenshot courtesy Electronic Arts

This is not to say that there are topics which games cannot or should not address through metaphor, but when there are clear real-world parallels to presented scenarios which affect marginalized groups, those groups notice. Players and developers alike should be paying attention to the way they are calling attention to the mutilated and misleading parallels games so often employ.

Dia Lacina’s Medium post about the Native imagery in Horizon Zero Dawn talks about her frustration with how both the game’s design and reception were handled. Laura Kate Dale wrote an affecting editorial for Polygon about the mishandling of trans characters in Breath of the Wild, Horizon Zero Dawn, and Mass Effect: Andromeda. Here’s a running list of every person of colour in Breath of the Wild from Xavier Harding (it’s not a lot). Patricia Hernandez covered the response from the LGBT community about the disappointing romances available for marginalized sexualities in Andromeda, especially for gay men. Waypoint’s Austin Walker and Cameron Kunzelman had a nuanced conversation about depictions of race in Watch Dogs 2. Gita Jackson wrote a piece for Offworld looking at similar questions of colonialism, and another on her relationship to Dragon Age: Inquisition for Giant Bomb.

There is an undeniable difficulty in telling postcolonial stories without stumbling into colonial-leaning traps and framings. When the landscape of game development is currently 76% white, it’s no surprise that there’s some significant struggle to tell other stories with nuance. It’s especially a challenge for those who, like Inkle, wish first to engage with tropes before reinventing and subverting them. It has worked for them in the past, and Inkle’s upcoming Heaven’s Vault, the studio’s first standalone release after 80 Days and their first release for console, is walking this same tightrope.

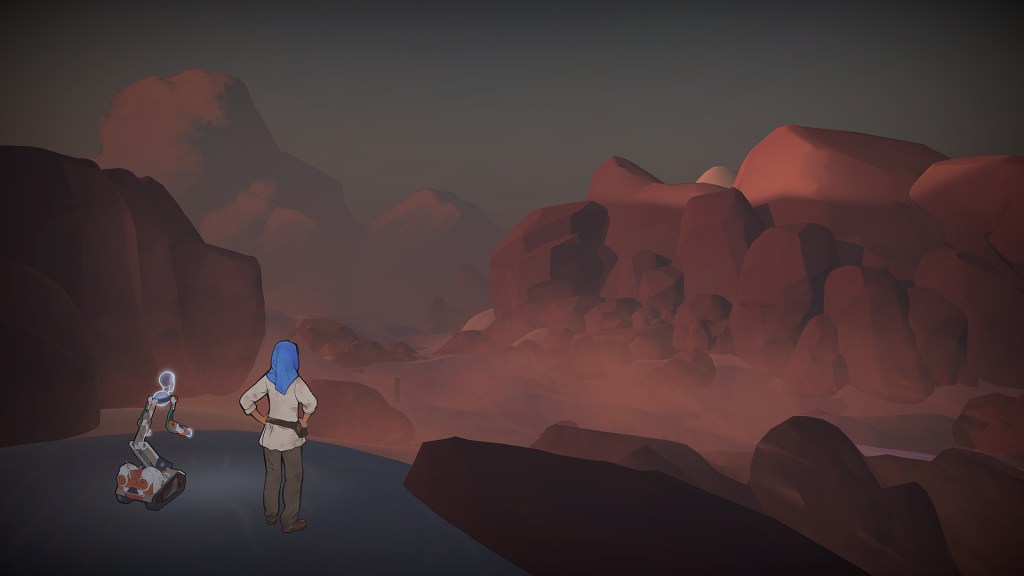

The game’s narrative will be handled entirely by studio co-founders, Joe Ingold and Joseph Humfrey, with Ingold currently slated to write the script. Heaven’s Vault features a diverse cast of characters, following Aliya Elasra, “an archaeologist who studies the lost places and forgotten history of the strange Nebula where she lives.” So far, the game looks and feels great. The core experience is built around a series of translation games, which are rewarding and clever, and world exploration is nuanced and expansive. But can Inkle manage to repeat what has worked in their previous projects, where so many other games—AAA and otherwise—have committed well-intentioned missteps?

It is fairly clear to tell from the character art for Aliya—and indeed, the rest of the art shown in previews for the game—the team has been influenced by Middle Eastern and South Asian imagery. Ingold described one character as a cross between, “a Bollywood actress and Hillary Clinton,” which, if handled appropriately, could be a stellar character. Could be. But Clinton represents many things, particularly in her own history with race issues and the way she has become an icon for a brand of white feminism. Whether she can be effectively crossed with a “Bollywood actress”—and indeed, what that term means beyond evoking an already exoticized stereotype— remains to be seen.

Further, even within the futurist-fantasy world of Heaven’s Vault, it is difficult to divorce the real-world implications of Al’s headscarf, patterns or styles for characters’ clothing, or a character’s gender. These markers are telling for traditionally marginalized audiences, and as seen in other examples of attempts to tell stories of these groups, certain aspects of Al’s character may require a nuanced hand to tell her story. To date, there are no people of colour working at Inkle on Heaven’s Vault, and two women in art direction—higher than the industry standard for women in game development for Britain, but these statistics point to the kind of structural issues which bedevil developers’ attempts to represent and speak to the experience of marginalized groups.

Yet for Inkle, these are the stories most worth telling.

“I think the diversity thing is really interesting,” Ingold said on the subject. “Because sometimes, we sit there and go—are we being diverse for the sake of being diverse? Or are we being diverse because the world just is diverse and it’s stupid to claim that it’s not? And—I think—if I’m actually honest, I don’t know what the answer to that is. And I don’t think I care. Because I think I’m doing probably not the wrong thing.”

“I love that completely outside of what is socially good,” Humfrey continued. “I love that [having a diverse cast] just genuinely makes everything a lot more interesting.”

In our further conversation, Ingold described the power relationships between Al and the director of the university where she works—a woman who is both her adoptive mother and her boss. The line between political intrigue and tense family dynamics is a fascinating one, but worryingly, might be overshadowed by a “father figure” for Al. According to Ingold, Al’s surrogate father is a bartender who lives in the slums where she grew up, and inspired by Humphrey Bogart’s pulpy detective in The Big Sleep, or his washed up hero in To Have and Have Not.

Heaven’s Vault screenshot courtesy Inkle

Ingold asked me, “You know how in 1940s films, there’s always that character who is like, twice the age of the heroine, but keeps offering to marry her?”

“Uh, yes?”

“But it somehow isn’t creepy?”

“No? Like—a Mister Knightley sort of thing?”

“I mean, he’s sort of like, he’s kind of okay about it—he’s just like, ‘Look, you know, if ever you think that maybe you want to actually get married—here I am, but it’s no big deal.’”

“Hmm.”

“And I really think that’s an interesting character that you just don’t see any more. And it’s quite hard to get it right. Because if you go too weird then it just—maybe it is weird?”

“It is pretty weird,” I said. “It’s pretty weird. Like—all the Hollywood actresses and then the men that they’re forced to act opposite? Like the Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson sort of thing?”

“Sure, and from that perspective it—”

“It’s kind of loaded.”

Humfrey laughed, and Ingold assured me, “If you just write safe relationships, what’s the point? If it’s just grim and violence all the time, there’s no point to that either. I’d rather do something which is sweet in the wrong way.”

“I’m having fun finding where the ick edge of that is,” Ingold ultimately said of writing the relationship. “Because it’s certainly somewhere.”

I’m not sure it takes much searching. With the number of actresses already playing opposite men who are almost twice their age, perhaps it is not so much to ask that this particular trope, as it gets written by men, could be left to the past. Mr. Knightley, it is not.

There are any number of pitfalls when a developer attempts to tell the stories of marginalized people. While making the choice to actively diversify one’s work is an admirable one, comments like Ingold’s and Humfrey’s can be concerning—they suggest a gap in their willingness to address the history of the stories they want to tell. When the market is saturated with stories for, about, and by white cisgendered men, stories about anyone other than that requires respect, intention, and care. It requires research, consultation, and a diverse development process. And this takes time.

Marginalized groups’ stories are few and far between, which adds pressure for those who choose to write them responsibly. They must demonstrate that they are conscious of the lived experiences of the groups they claim to represent, they must address and subvert stereotype. Walking this line between the two takes an adroitness beyond considering the challenge interesting, or benefitting a social good. It is a walk weighted by history, and steeped in contemporary socio-political tensions as well as diverse populations of players who just want to play a game which can speak to them.

These approaches to Inkle’s design and narrative for a game still in its early stages of development are worrying, but not damning. They are examples of a wider trend in an industry where more developers are trying to be better with these issues by looking at smaller games from industry fringes, or from marginalized groups, and also by listening to thoughtful criticism.

Ingold and Humfrey are well-intentioned, and Al’s story should be told. There is no question about this. However, these conversations are also examples of how sometimes despite the best of intentions, this industry can invite marginalized people to share their insight, their stories, their criticism, their resources… without being invited into the creative process itself. And so it gets weighed down by context and scrutiny.

When decolonization starts at development, when more stories by more people are told, this weight might be slowly lifted. But here in the early stages of that process, it’s clear that the burden remains heavy.