It was nearly 2 o’clock in the morning on Oct. 23, 2010, when an Air Force lieutenant called from his base in Wyoming to report the nightmare scenario unfolding before him. Fifty intercontinental ballistic missiles — each tipped with a nuclear warhead 20 times more powerful than the bomb the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima — had suddenly lost contact with the computers at the base’s launch center.

“I… we… have no idea what’s happening right now,” the officer sputtered as he tried to explain the situation to support staff at a remote command center. Another officer barked orders behind him, interrupting the call. “Holy shit!” the lieutenant exclaimed. “I will have to call you back!”

Videos by VICE

The Air Force could tell that the weapons were still in their underground silos, but there was no way to know whether the missiles had been hijacked. A renegade missile crew, someone splicing into underground cables, or hackers exploiting radio signal receivers attached to the ICBMs could have set them on a countdown to launch. Even worse, without contact with the missiles, it was impossible to halt an unauthorized launch attempt.

Fortunately, the missiles were undisturbed. Altogether, they were knocked offline for a total of about 45 minutes, and the entire situation was resolved in a matter of hours. But for a chaotic stretch during the blackout, nobody knew what was wrong or how to fix it. As one colonel put it in an email, “the weapon system was kicking our butt.”

The culprit turned out to be a simple computer glitch: A circuit card had popped loose in the brains of the base’s Weapons System Processor.

The Air Force maintains that the situation was always under control. Still, it’s a stark reminder that even a minor mishap involving our nation’s aging nukes could have catastrophic consequences.

The U.S. keeps 416 “Minuteman” missiles ready to blast off at a moment’s notice. It’s unlikely — but not impossible — that a false alarm could make it seem like an attack is underway. In such a scenario, President Donald Trump, who has the sole, unchecked authority to launch U.S. nuclear weapons, would have only a few minutes to react. The codes used to fire the missiles are about the length of a tweet. And once one is launched, there’s no taking it back.

The technology that currently powers these nukes is notoriously antiquated. Most of the systems were designed and built during the height of the Cold War in the 1960s and ’70s, with the last major overhaul completed during the Reagan administration. Some computers in the missile base command centers still use eight-inch floppy disks.

In a May 2016 report, the Government Accountability Office determined that a key component of the Defense Department’s “command and control system,” which would be used to either start or prevent World War III, is “made up of technologies and equipment that are at the end of their useful lives.” The Pentagon is now in the midst of a $60 million overhaul of the system, which is expected to be complete by 2020.

The U.S. is on track to spend about $1 trillion over the next three decades upgrading all facets of the nuclear arsenal, with $3.2 billion already budgeted for the 2017 fiscal year. A large chunk of that money will go toward upgraded missiles, new infrastructure, and overhauled command-and-control systems, such as digital phone lines and modern computers. Obama initiated the modernization plan, but it has found a new champion in Trump, who wants to boost the nuclear weapons program budget by an extra billion dollars.

“Our nuclear program has fallen way behind and they have gone wild with their nuclear program. Not good,” Trump said during a 2016 presidential debate. “Our government shouldn’t have allowed that to happen. Russia is new in terms of nuclear and we are old and tired and exhausted in terms of nuclear. A very bad thing.”

Shortly after he took office, Trump ordered a review to “ensure that the United States’ nuclear deterrent is modern, robust, flexible, resilient, ready, and appropriately tailored to deter 21st century threats and reassure our allies.”

U.S. nuclear missile base technology is ancient by modern standards, but the old machines offer almost maximum cybersecurity simply by virtue of their age. With everything hardwired and analog, the system is uniquely impervious to intrusion and meddling. That leaves some nuclear experts to ask: Why spend billions switching from a system that is relatively safe to one that’s potentially more vulnerable?

“If it isn’t broke, don’t fix it,” said Andrew Futter, a professor at England’s University of Leicester and a member of the cyber-nuclear security threats task force at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit. “This system might be old, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s bad. Just because we can control this from an iPad doesn’t mean we should.”

Cyberwarfare has already moved into the nuclear realm. The U.S. has reportedly attempted to digitally sabotage North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs, perhaps as recently as last week, and it’s widely believed that malware created by the National Security Agency infected computers at an Iranian uranium-enrichment facility in 2010.

In February, the Pentagon issued a report on “cyber deterrence” that addressed the threat posed to nuclear weapons at home. It warned that “the cyberthreat to U.S. critical infrastructure is outpacing efforts to reduce pervasive vulnerabilities.” In other words, the bad guys are coming with new ways to attack digital weak spots faster than we can fix them.

As the mishap in Wyoming shows, the aging computers that control America’s nukes are by no means perfect. But with the modernization process already underway and multiple experts raising concerns about the plan to bring the most dangerous weapons known to man into the 21st century, the question is whether the solution to repair the creaky old machines is more dangerous than the existing problem.

Shortly after the frantic lieutenant reported the disappeared nuclear missiles, the commanders on duty at F.E. Warren Air Force Base decided it was time to rouse a colonel for his first briefing on the situation. It was 3:17 a.m. on a Saturday.

“I hate to wake you, but I have to run something by you real quick,” the caller began. “First of all, nothing has inadvertently launched and nobody is dead. Let me just start off this way.”

“Well,” the colonel replied, “then everything is good.”

The officer proceeded to report a “black squadron,” which meant that the base’s command center had lost contact with some of its missiles. Normally, the computers would provide constant updates about the status of each missile. Now, as the officer put it, “Nobody could see nothing.”

The machines that should have allowed the Air Force to “see” the missiles are as old as the weapons themselves. The ICBMs were designed in the 1950s as the first means of counterattack in a nuclear war against the Soviets. The advent of solid propellants — a combination of fuel and oxidizer — meant that properly maintained missiles could sit on standby for years in their silos, ready to launch within minutes if the president ever needed to give the order, hence the “Minuteman” name.

The current Minuteman III missiles were deployed in the ‘70s and refurbished several times over the past 15 years — at a cost of more than $7 billion — with new guidance systems and propellants. Each one stands about 60 feet tall and has a range of about 8,000 miles. They are still controlled by an IBM Series/1 Computer, a hulking old machine that’s been obsolete in other contexts for more than three decades.

The Air Force Scientific Advisory Board — a 50-member panel that includes experts from academia and the private sector — is conducting a study to determine exactly how to overhaul the technology used to control the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Werner Dahm, the advisory board chair, declined an interview request, but he was quoted in December as saying future nuclear weapons systems will be “network-connected” and “cyber-enabled.”

Lt. Gen. Jack Weinstein, the deputy chief of staff for strategic deterrence and nuclear integration, declined to discuss Dahm’s comments, saying it would be “premature” to comment on what the next generation of nuclear weapons technology might look like. But in interviews with nearly a dozen independent experts on nuclear weapons, all found Dahm’s use of the buzzwords “network-connected” and “cyber-enabled” troubling.

“We need to have a much better understanding of the vulnerabilities that exist even in the current system, which is not networked and not cyber-enabled in any of the ways that [he] mentioned,” said Kingston Reif, director for disarmament and threat reduction policy at the Arms Control Association.

There are multiple arguments against mixing nukes and modern technology. The doomsday scenario involves terrorists hacking the missiles and launching them all, but that’s just one nightmare on a spectrum. Russia, China, or North Korea could infiltrate and sabotage the system. A software bug could create the appearance of an attack, prompting the president to order a counterstrike. The list goes on.

“It’s simply impossible to protect networked devices from cyber threats,” said James Acton, co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “Against highly sophisticated adversaries, when it comes to nuclear operations, I just don’t understand — it’s not clear what the advantages of networking those weapons are, and it’s unclear whether any advantage could outweigh the huge disadvantages.”

The Pentagon’s 2017 report echoed that assessment, stating that “new nuclear capabilities” should not be “networked by default.” The report warned, “connectivity may make such capabilities more modern, but it also widens their attack surface to adversaries.”

The Air Force, which controls two-thirds of the so-called nuclear triad of missiles, stealth bombers, and submarines, plus 75 percent of the military’s nuclear command, control, and communications systems, is not transparent about the cybersecurity of its nukes, nor its plans for the future. Top officials have offered reassurances to Congress, but much of the information remains classified, or has been publicly discussed only in broad terms.

Weinstein wouldn’t discuss specifics, but he said he’s not worried about American nukes getting hacked, now or in the future.

“I’m not concerned,” he said. “Let’s just say that I am acutely aware of what the strategic environment looks like from countries that are out to do harm. I am aware of the talent that exists in our national laboratories, as well as internal to the United States Air Force, on what it takes to develop new systems. It’s not something I’m concerned about.”

The existing U.S. nuclear weapons system is completely air-gapped, which means it has no direct connection to the internet or to other computers that are online. The missiles are connected to underground command centers via hardened underground cables. Future setups will almost certainly involve similar precautions, but even then there’s still no guarantee of full security.

In 2010, for example, the Stuxnet computer worm crippled Iran’s development of nuclear weapons. Stuxnet, described as “the world’s first digital weapon,” made computers at an Iranian uranium-enrichment facility to go haywire, destroying hundreds of centrifuges. Experts think the virus was introduced to the air-gapped system by an infected USB stick.

“We have a popular conception of hackers going through the internet, the ‘War Games’ side,” said Futter, the nuclear cybersecurity expert. “In reality, a lot of cyberattacks take advantage of good old-fashioned human error and weakness.”

The Air Force’s investigation into the Wyoming incident revealed that something similar had happened before — twice.

On June 5, 1998, while workers were installing new circuit cards in a missile base computer, the Air Force briefly lost the ability to monitor an entire squadron’s worth of launch facilities. The same thing happened just two months later, on Aug. 28.

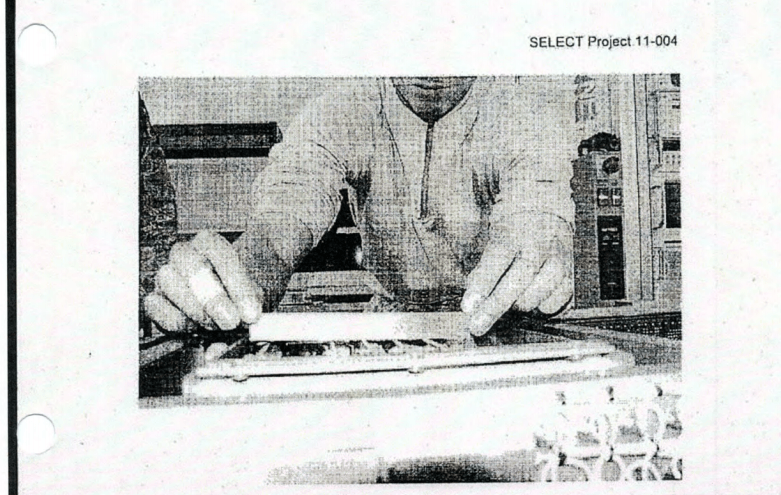

In 2010, it turned out that a maintenance worker had installed a new circuit card about 10 hours before the missiles went offline. The card popped loose, either from low-level vibrations or because it wasn’t inserted properly, creating a tiny 1/16-inch gap where it was supposed to be connected in the computer’s mainframe.

The proposed solution to avoid a repeat scenario, according to Air Force documents reviewed by VICE News, was determined to be “a permanent hardware fix.”

Fixes and general upkeep for these ancient machines is getting expensive. The 2016 Government Accountability Office report found that maintenance for the Strategic Automated Command and Control System costs about $75 million per year, largely because “replacement parts for the system are difficult to find because they are now obsolete.”

The job of designing and building the new systems will fall to defense contractors, which are currently submitting bids to work on the project. The Air Force is already set to pay Lockheed Martin nearly $600,000 to repair a Weapons System Processor used on the Minuteman III missiles, with the work expected to be completed by November.

While it’s costly to keep the old equipment running, modernization skeptics say that the rapid pace of technological advancement tends to make new things obsolete within a matter of years. The British Royal Navy learned this lesson the hard way less than a decade ago when it opted to install a customized version of the Windows XP operating system on its ballistic missile submarines. Microsoft stopped providing security updates for Windows XP in 2014, which makes the system vulnerable to glitches, viruses, malware, and cyberattacks, though there are reportedly “special safeguards” in place for nuclear-armed subs.

“It was only 2008 when [the British Navy] did that,” said Jeffrey Lewis, director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. “People applauded them — ‘Good on the Royal Navy for using cutting-edge, off-the-shelf technology.’ But the life cycle of a nuclear weapon is so long you’ll end up with obsolete or archaic technology eventually.”

Security and cost concerns aside, the case against modernizing America’s nuclear weapons systems boils down to the belief that the computers and missiles currently in use have already stood the test of time. Critics of the modernization plan readily concede that the technology is primitive, but they also point out that it still gets the job done.

“There’s nothing wrong with our nuclear weapons,” Lewis said. “There was nothing wrong with the bomb we dropped in 1945. It was a dumb bomb and it worked just fine. Why are we trying to make our weapons more fancy?”

Futter believes an unintended consequence of modernization might be that simple fixes — like reinserting a loose circuit card — will no longer be so simple.

“What you’ll eventually have are people in the command center at NORAD [the North American Aerospace Defense Command] or Stratcom who don’t understand how these systems work,” Futter said. “Therefore, accidents we avoided in the past, where the computers gave erroneous reports of things happening, might not be as easy to stop in the future.”

In response to the Wyoming incident, President Obama ordered an investigation into “the possibility of a rogue actor hacking into the U.S. nuclear arsenal and launching an attack.” The result of the inquiry — an 88-page report titled “Red Domino” — has remain classified since it was completed, on Dec. 11, 2011.

Recently, there’s been a push for renewed scrutiny of the report. The organization Speaking Truth to Power, which advocates for greater transparency about nuclear weapons, has filed a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit seeking to have the report made public. The group’s founder, Philadelphia attorney Jules Zacher, has published a trove of documents about the missiles going offline in Wyoming. VICE News reviewed the records for this story, including emails, internal reports, and verbatim transcripts of phone calls by base personnel.

Separately, Bruce Blair, a researcher at Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security, wrote an op-ed for the New York Times last month claiming that Red Domino uncovered how the “Minuteman missiles were vulnerable to a disabling cyberattack.”

Blair is uniquely qualified to understand the flaws in the system. From 1972 to 1974, he served in the Air Force as a missile launch control officer in charge of 50 Minuteman ICBMs in Montana. Since leaving the military, he has frequently been called upon to testify before Congress as an expert on nuclear weapons, and he recently served as a member of the Secretary of State’s International Security Advisory Board. He is also the co-founder of Global Zero, an international movement that advocates for the total elimination of nuclear weapons.

“We find ourselves today with enormous uncertainty about the cyber vulnerability of our nuclear command-and-control and early-warning networks,” Blair said in an interview. “We’ve discovered, repeatedly, some really major problems. We don’t know whether that’s the tip of the iceberg or if there’s deeper problems.”

Robert A. Morris, a retired Air Force colonel who specializes in cybersecurity, said the report did not expose major cyber vulnerabilities. And Morris would know — he was one of the co-authors.

“Quite frankly,” Morris said, “everything came back clean — we really didn’t find anything.”

Without access to the report, it’s impossible to know how significant Red Domino really was. But the military clearly remains concerned about cyberattacks on the nuclear arsenal. The Pentagon report from February called for an “annual assessment of the cyber resilience of the U.S. nuclear deterrent.”

Blair said he’s most concerned about the potential for hackers to “corrupt the early-warning data that is the basis for presidential decisions on the use of nuclear weapons in the event of an apparent attack on the United States.” Basically, he thinks it’s possible to trick the Air Force’s computers into thinking Russian or Chinese missiles are headed toward U.S. cities. And then trick military commanders into launching a counterattack.

“These briefings have to be made really fast, and are based on data that could be corrupt, that could be really wrong, could even be a mirage that somebody has created,” Blair said. “That vulnerability exists today. It still hasn’t been fixed.”

The Air Force vigorously disputes any suggestion that nuclear missiles could be launched because of a false alarm. Weinstein said there are “many different levels of safeguards” and “a very rigid command-and-control system when it comes to executing weapons.”

“ICBMs are not on hair-trigger alert,” he said. “ICBMs provide the most responsive force that provide the president of the United States options depending on the strategic environment at the time.”

Regardless of what the U.S. decides to do with its aging nuclear weapons systems, there will still be the possibility of human error. And with Trump in the White House, the fear that the commander-in-chief will blunder into a nuclear war has never been higher.

Two Democratic lawmakers, Massachusetts Sen. Edward Markey and California Rep. Ted Lieu, introduced a bill in January that would prohibit the president from launching nuclear weapons without a declaration of war from Congress. An online petition in support of the measure has accumulated nearly 200,000 signatures. But with Republicans in control of both the House and Senate, the legislation is doomed to fail.

The truth is that nobody — not even the Secretary of Defense or the Joint Chiefs — could stop Trump from ordering a nuclear missile launch. As President Nixon once said, “I can go into my office and pick up the telephone, and in 25 minutes 70 million people will be dead.”

Indeed, while the independent experts who spoke with VICE News expressed varying degrees of concern about the Air Force’s plan for modernizing the U.S. nuclear program, they often seemed more worried about the man calling the shots. The Arms Control Association’s Reif pointed to Trump’s “behavior, judgment, and temperament,” and wondered whether a national security crisis would lead to the first nuclear attack since World War II.

“Cooler heads may not always prevail,” Reif said. “The 72 years of nuclear non-use may not last forever because human beings are fallible — Donald Trump seemingly more so than others.”