In 1969, Michael Humphrey did a 14-month stretch at the Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield, Ohio, on a grand larceny conviction stemming from an auto theft case. He was 18. Determined not to return, Humphrey says he never got in trouble with the law again, taking care not to so much as spit on the sidewalk after his release. Life was pretty good, or at least became tolerable when Humphrey finally overcame the nightmares about prison that had plagued him for years.

“I could still smell that place, I could still hear it,” he says now. “I’d have to get out of bed at night and turn the light on just to prove to myself I wasn’t still there.”

Videos by VICE

But on a spring day in 2000, Humphrey was driving along Route 30 and saw a sign advertising tours of the reformatory, known colloquially as Mansfield. The place had been shut down by court order a decade earlier, just over a century after it opened, due to inhumane conditions.

Despite his reluctance to reenter that world, curiosity got the best of Humphrey. So he drove up to the striking gothic façade that led early prisoners there to dub it “Dracula’s Castle,” paid the admission, and went inside again.

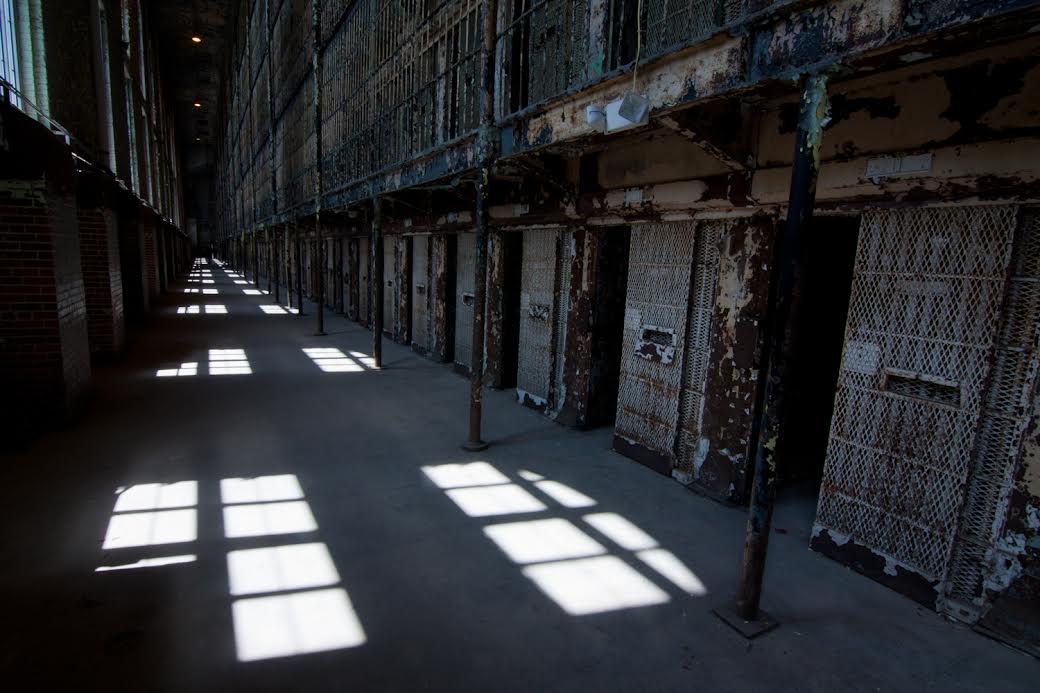

By this time, Mansfield had found new life as a burgeoning tourist attraction thanks to the fact that the revered 1994 movie The Shawshank Redemption was filmed there (scenes from other, lesser films like Air Force One and Tango & Cash were shot there as well—the latter while Mansfield was still an operational prison). Humphrey walked around the sprawling facility, taking in the surreal decay and once more coming face to face with his temporary residence on the East Cell Block—six tiers high, it’s still the world’s largest free-standing steel cellblock.

Photo by Michael Goldberg

“When I was there [as an inmate], we never got to wander around the place, so it was kind of an adventure,” Humphrey chuckles drily, admitting he began second-guessing his visit once the unpleasant memories started flooding his mind. A few weeks later, he contacted the Mansfield Reformatory Preservation Society and explained his history with the place, and by the fall, Humphrey was serving as a tour guide. Because of his background in construction, he helped rehab and preserve the crumbling structure, too.

Now 66 years old—nearly a half-century after his release—Humphrey has come full circe, outing himself with his popular “Life of an Inmate” tour that gives Shawshank aficionados and other visitors an unflinching look at Mansfield incarceration from someone who lived it.

“When I first started doing tours [in 2000], I didn’t tell anybody that I was a former inmate,” he explains. “I was so ashamed of actually being a convicted felon.” Humphrey says he almost quit early on, stung by the fact that he “would hear people make jokes and dumb remarks [about inmates], you know, ‘They shoulda done this to him, and they shoulda done that to him.’”

Now he tells people anything they want to know while providing a detailed history of the prison and how it evolved from a rehabilitation-minded intermediate penitentiary for young, largely non-violent offenders to an overcrowded and intensely violent maximum-security hellhole.

The sea change can be traced to a 1930 fire at the higher security Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, approximately 70 miles south of Mansfield, that killed more than 300 inmates. The damage forced the state to transfer hundreds of “the worst of the worst”—murderers, rapists, and others—to Mansfield.

The first thing Humphrey noticed after being committed to the facility in 1969 was the overwhelming, horrible stench of more than 2,000 men who were allowed to shower just once per week. The violence revealed itself soon after: Fights happened like clockwork, stabbings were a regular fact of life, inmates hanged themselves. The most terrible things you can imagine happening behind bars happened at Mansfield, according to Humphrey, who fashioned his own weapon early on in his stay. “I had a toothbrush with a razor blade melted into the handle of it that I carried around my neck on a string, but in the nape of my neck so no one could really see it.” Thankfully, he says, he never had to use it.

Photo by Michael Goldberg

Humphrey’s cellmate was a man named Ron Crabtree—six years Humphrey’s senior and in on an armed robbery conviction. The two wound up being lifelong friends (Crabtree died in 2012) and was essentially “Red” to Humphrey’s “Andy Dufresne,” showing him the ropes and teaching him the number one rule of Mansfield (or any prison): “Do not accept any gifts from anybody.” “

“Nothing in here is free,” Humphrey recalls being told, “and I heeded that warning very well.”

Humphrey mainly kept to himself during his 14 months and says he got along well with the guards. Not because he was helping them with their taxes, but because his mother would bring huge trays of lasagna and chili to him during her bi-monthly visits, and the guards would end up taking the massive leftovers downstairs for a hell of a feast. “It went from ‘Ma’am’ to ‘Mrs. Humphrey’ to ‘June,’” Humphrey laughs. “And they treated me pretty well.”

Another fairly important parallel between Humphrey and Shawshank: Just like Andy Dufresne, Humphrey says he was innocent. He didn’t steal that car.

“Don’t get me wrong, I was no angel, but I wasn’t a criminal,” he says. “I took the blame for something some other guys were doing. The day the police came to the house, I was the only one there, and they took me. The judge insisted that I tell him who all was involved, and I wouldn’t do it, and that’s when they sent me to Mansfield.”

Nearly 50 years later, he has little regret about that decision. “I could have gone to work at Republic Steel with my father and died of black lung like he did,” Humphrey says. “If this was the plan for me, so be it.”

At the time, Humphrey figured, he’d just pay the price, figuring once he was paroled, things would be fine. They weren’t. Beyond being stripped of rights like voting or gun ownership, Humphrey, like many other former inmates, carried with him an unyielding sense of stigma and shame about being a convicted felon. But thanks to the support and encouragement of his colleagues at the Mansfield Reformatory Preservation Society, he filled out the necessary paperwork, and in May 2004, then Ohio governor Bob Taft pardoned him.

“It’s still emotional for me,” Humphrey says. “I can’t begin to tell you what it did to me, but it absolutely changed me for the better. It took that weight off my shoulders. I’m happy now. I can talk to anybody and not feel like a second-class citizen.”

There aren’t any more nightmares, but there are areas inside Mansfield that still bring back terrible memories. Yet even in his darkest of times during his incarceration, Humphrey never considered “crawling through a river of shit” or any other means to escape. “I just never wanted to be looking over my shoulder,” Humphrey says. “I’ll say this, though—I wanted out pretty bad, and in ’69 and ’70, when I looked at those guards carrying those keys, I sure wished I had them.”

He laughs. “And now I do. I have the keys to the place.”

All photos Michael Goldberg

Follow Michael Goldberg on Twitter.