“Together,” a man’s voice intones. And then an onslaught of voices. Two are in front, a man and a woman; if they’re actually saying words, they’re impossible to decipher. It’s just syllables rolling together, the sound of lips flapping and tongues rolling over a single note. There’s something insectine about it, its nasality and its density, like a fog of cicadas descending. Occasionally—every few minutes or so—both of the leads stop to take a breath. You can really hear the congregation then: hundreds, maybe thousands of voices droning in a cavernous room, every tone and pitch in the musical spectrum. It is a great, heaving cloud of voices.

I’ve heard mantras and chants before but this sounds different. It’s insistent, for one thing. The energy is turned outward, instead of inward. And the intensity jacks upward every five minutes or so, the voices all become louder together and raise pitch a half-step, like a phalanx of semi trucks shifting up at the same time. After 27 minutes of these intensifications, the chanting is fast, high-pitched, the kind of thing that makes your eyeballs want to jump out of their sockets. The image in the mind is a congregation in the thousands, knelt down, eyes rolled back, filling their lungs with their intentions. What are they asking for? Then, abruptly, it stops. “Please be seated,” says the woman.

Videos by VICE

I looked it up right after the first time I heard it—on the Avant Ghetto show on WFMU, New York’s venerable free-form radio station—and located it online right away. It’s an old recording of the Church Universal and Triumphant, from an album entitled Sounds of American Doomsday Cults, Vol 14, released by a mysterious imprint called Faithways International. The cover, which had been copied and posted online along with mp3 files, is austere, an obvious homage to the old Smithsonian Folkways releases—a picture of a lighthouse, lime green and pink background. As far as anyone on the internet knew, there were no Sounds of American Doomsday Cults Volumes 1 through 13. The label, according to the internet, had only one other release to its name: a collection of original tunes by Aum Shinrikyo, the cult that killed 12 Japanese subway commuters in a terrorist attack in 1995.

History and half-researched mythology blend together in the internet’s accounting of the Church Universal and Triumphant recording’s origins. CUT was a group in rural Montana that was at one time centered around Elizabeth Clare Prophet, who believed herself a reincarnation of Marie Antoinette and Guinevere who could channel a pantheon of saints that included Jesus, Hercules, and Shiva. Pictures show a woman with a perm and a dead-eyed grin—perhaps the most homespun-looking doomsday cult leader of all time. It was Prophet’s voice I’d heard leading the chant. The recording originated sometime in the mid-80s. No one knew who had made the recording. No one knew who Faithways International was. No one knew where Sounds of American Doomsday Cults, Vol. 14 had come from. I reached out to the DJ who’d played it on his show—they were just some mp3s he’d found online a few years ago, he said.

I downloaded them. The entire recording is plainly amazing. Sitting through the entire 27-minute chant is a rush, consuming and burying, like being swallowed up by human voices. It has a touch of the supernatural; it exists somewhere beyond music. It’s thoroughly of its own making, science fictional. The rest of the recording is maybe even more fascinating: an entire Church Universal and Triumphant service dedicated to “the tackling of the beast and the dragon—the momentum of rock ‘n’ roll.” Mostly, it’s Prophet’s voice, preaching about the sexual perversion of rock music, saying outrageous things that are both hilarious and truly inspired. Chanting alone, she prays for those “subverted by the syncopated rhythm of the fallen ones and the misuse of the 4/4 time.” She “calls on the electronic solar rings of the great central sun.” She plays the music video for Tina Turner’s “Better Be Good to Me.” The man, when it’s his turn, “calls forth the sacred fire” in nasally solemnity on a list of 71 contemporary rock and roll celebrities including Michael Jackson, Kenny Loggins, the Alan Parsons Project, “Cyndi Looper,” and “Scooby Dooby Doo.”

I felt like I’d found a buried amulet. There was something slightly morbid and voyeuristic about my interest—these are, after all, real people’s prayers. I wanted to know what I was hearing; what the room looked like; what they were saying. And who was this shady Faithways International label that put the album out? With slightly nosy intentions—like flipping through the pages of someone else’s family bible—I tried to find where it had come from.

Continued below…

I was joining a group of curious listeners, sound artists, and avant garde music obsessives who have been fascinated by the recordings for decades. The spoken parts of the album—the parts about Tina Turner and Cyndi Looper—had been a hit for years with underground DJs and experimental composers. Genesis P-Orridge of Throbbing Gristle once said they brought it with them every time they DJed. Negativland, dissident sound collagists and copyright crusaders who’d once thrown down with U2, sampled the “sacred fire” rock ‘n’ roll-call on a piece called “Michael Jackson” way back in 1987. Fatboy Slim sampled it in 1996 and also called his piece “Michael Jackson.”

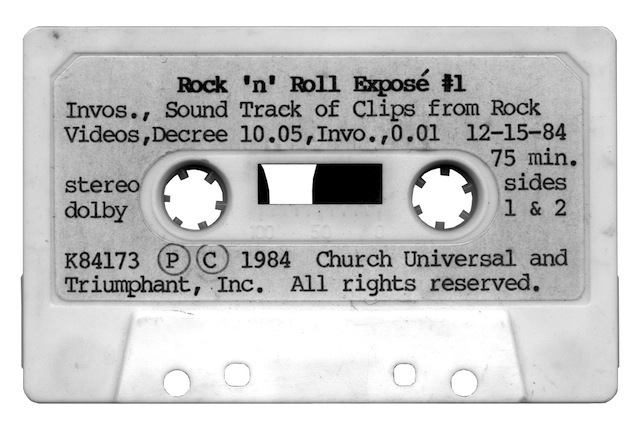

Negativland’s Mark Hosler said they found the original tape of the Church Universal and Triumphant service back in the mid-80s. It was titled “Rock ’n’ Roll Exposé #1,” copyright Church Universal and Triumphant, Inc. This wasn’t the Sounds of American Doomsday Cults CD, but the source material.

Negativland

“It sure wowed us back then,” Hosler told me. “[It] cried out to be used.” But it wasn’t Hosler who found the tape—he said it was either band members Ian Allen or Don Joyce. Could either of them have been behind Faithways International? We might never know—they both sadly passed away earlier this year—though it doesn’t seem likely.

A hard copy of Sounds of American Doomsday Cults, Vol. 14, which was issued by Faithways in 2000, is not easy to find. It’s out of print; every once in awhile, someone puts a CD or vinyl copy of it on sale for $100 (outside my writerly budget). I called Aquarius Records, the oldest record store in San Francisco, the city where everyone who discovered the recording seemed to have found it. But since the CD is out of print, the store doesn’t carry it anymore. And none of the people I talked to there knew where it came from (though one clerk said he still subscribes to new recordings from the church—they still put them out on CD-R and ship through the US Postal Service—because “they’re awesome”).

I eventually found a copy on the internet’s back pages—a guy named Earl Kuck was selling them on his website, Tedium House. He told me he bought a box of the CDs at a record fair in San Francisco ten years ago. He sent it to me in a package along with a wooden snake, the last page of an angry hand-written note, and a copy of Le Carillon by the Autumns. The packaging of the CD is simple—a pink booklet with two reprint news articles about the cult and nothing in the way of credits.

Kuck said he didn’t know where the CDs he bought had come from, but he thought someone in Australia had made them. He connected me with another San Francisco friend, a guy named “Seymour Glass” who’d reviewed the “Rock ’n’ Roll Exposé” version of the tape for his underground zine Bananafish. “Glass” had an experience similar to mine when he heard it. “The first time I listened to the tape, I sat staring at my stereo with mouth agape for the duration,” he wrote. “I returned to the bookstore and bought every copy they had. I’ve made more recordings of this tape than any other.”

I managed to get a hold of “Glass” (the name on his email was “Maria Estevez”) who confirmed he found the tape at a since-shuttered bookshop in San Francisco, which led him to lament “the plague of start-ups and luxury condos” in the city.

“I have a long history of exploiting (I guess you could say) these recordings I love,” he wrote me, “and have been told numerous times that I am suspected as, if not assumed to be, the disc’s midwife. It’s nice to be remembered.”

Now, I had it on background that “Glass” and Kuck are the same person and that neither name (surprise!) is real. It would make sense that they/he were the one/s who put together the Doomsday Cults CD from the original tape. Both claimed they didn’t know its origins, which was, of course, in keeping with the tone and tenor of this whole affair. I became convinced—and still am— these merry pranksters were, in fact, the “midwives” of the CD; that they’d taken the old tape and cleverly repackaging it. But they’d never tell me if they did, so I kept poking around for good measure. (I told Kuck I had heard him and “Glass” had never been seen together in the same room. He replied: “He and I are in the same room together frequently. People just aren’t observant enough to notice.”)

Brian Turner was, as far as I could tell, the first WFMU DJ to spin Doomsday Cults 15 years ago, when it was first released by Faithways. He’s also the music director. I was sure he would have some insight. He didn’t know where it came from, but he said that when it first came out in 2000, he’d gotten his own copy in the mail. That’s not that weird for him—he’s the music director at a radio station, after all—but when he opened the package, he was startled to find he was thanked by name in the credits. He ventured a couple guesses about who put it out. “Elizabeth Clare Prophet has been touted by weird sound connoisseurs like [Gregg] Turkington, [Germs and Ariel Pink drummer] Don Bolles, and the ilk,” Turner told me. Otherwise, he had no clue.

Gregg Turkington is famous in the comedy world for creating the Neil Hamburger anti-comedian character. He’s also Australian. I felt like I might have been on the right track. I reached out to him right away, but got only a brief message in reply: “I had nothing to do with that record,” he wrote. “I have no idea who actually was behind it… though if I recall correctly, I’m thanked in the liner notes.”

I got a reply back from Don Bolles right after. “No,” he wrote. “But my name was on it.” Elizabeth Clare Prophet laughed at us from beyond the grave.

***

Photo: Earl Kuck

In 1875, a Russian immigrant in New York City named Helena Blavatsky formed the Theosophical Society with her friends. Blavatsky claimed to communicate with a host of spirits, including Jesus. The society sought to unite world religions into a single belief system, and by the time she died in 1891—of influenza, at the top of a growing organization, besieged with accusations of fraud—she’d launched Theosophical Society enclaves in India, Europe, and Russia.

Forty years later, Theosophy had made headway in America—including to Chicago, where Guy Ballard, a Blavatsky acolyte, founded the I AM movement in the early 30s with his wife Edna. Ballard, like Blavatsky, believed he could communicate with a spiritual dream team, whom he referred to as the Ascended Masters and expanded to include Buddha, Confucius, and the Virgin Mary. (He believed himself to be the reincarnation of George Washington.) The Ballards led their growing membership through marathon “decrees”—composed prayers shouted out loud by the entire congregation during services. In 1939, Ballard died suddenly, and immediately afterward, Edna and their son Don were both indicted by the federal government for mail fraud (which they fought and won before the Supreme Court in 1946). The I AM movement, like the Theosophy Society, had sprouted many groups of followers.

One of those followers, Mark L. Prophet (his honest-to-God birth name) founded the Summit Lighthouse in 1958. Like Ballard, Prophet claimed to communicate with venerable ghosts (he adds Hercules and Shakespeare and many more to the list). Like Ballard, claimed to have been reincarnated (in his case, Sir Lancelot and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow); and, like Ballard, Prophet’s wife Elizabeth Clare could chat with Ascended Masters, too.

The New Age movement of the 70s provided a glut of washed out and disenchanted hippies that swelled the Summit Lighthouse’s membership rolls. Like the Ballards before them, the Prophets wrote decrees for the congregation to chant, but with less shouting and more of a controlled drone. During services, the Prophets would specify an intention—for example, the judgment and destruction of rock music—and the congregation believed their decrees, if they were forceful enough, could make the intentions come true. They could turn the tides of history without going outside the walls of their sanctuary. (In other words, what I’d heard as music, church members considered serious prayer.) Sometimes, while the congregation decreed, Elizabeth would swing an actual steel sword over her head, sometimes for hours. The faithful called her “Guru Ma.”

When Mark Prophet died in 1973, Elizabeth moved the church to Los Angeles and renamed it Church Universal and Triumphant. In 1986, as she amassed members and money, she moved again, to a 30,000 acre ranch just north of Yellowstone National Park she bought from Malcolm Forbes.

In these days, Elizabeth Clare Prophet is on fire. She’s built the Church Universal and Triumphant into a religion with something like 30,000 adherents. She’s leading marathon services to 2,000-or-so believers who live with her in Montana. And she’s starting to get messages from the Ascended Masters about doomsday. She shifts the church into full-on prepper mode. The church commenced building underground fallout shelters big enough to house 750 people, started stocking weapons, and stored thousands of gallons of gas in giant tanks.

In the early 1990s, she told followers that Soviet nuclear missiles would fall on the United States at midnight on March 15. Local pharmacies reported being sold out of medicine, Band-Aids, bottles of water; banks said customers were lining up to close their savings accounts. “It’s bizarre,” a bank official told the Los Angeles Times in March. “They don’t want to wait, they want it now, and they want it in cash.”

One night near the apocalypse, one of the church’s members, packing up his things, had his own kind of religious epiphany. It centered on the band Rush. 25-year-old Sean Prophet, only son of Elizabeth and Mark, often helped his mother spread her anti-rock and roll propaganda, but he nursed a secret: He loved prog rock.

That night, Sean impulsively put on his headphones and listened to Power Windows—for research, he told himself—and was surprised to find himself moved to tears. He listened to at least five more Rush albums that night. Later, he wrote, “the idea that such talented musicians could be ‘fallen ones’ as the church taught just didn’t add up. They felt like brothers to me.” The experience changed him. He decided he’d stick around to see if the world did in fact end (never hurts to hedge your bets) and if it didn’t, he was out.

On the night of March 15, hundreds of adherents crouched in the cult’s homemade shelters, amid fetid buckets of human waste (the plumbing wasn’t finished yet). The sun set on the compound that night and (surprise!) rose again the next morning. Devotees started to pack up and go home. Sean and his family cut their final ties with the cult in 1993. (Incidentally, one of Sean’s sons, Chris, grew up to play drums in Horse the Band.) In 1999, Elizabeth stepped down from the church—she’d developed Alzheimer’s—and died in 2009. The Church Universal and Triumphant does still exist, albeit diminished both in its scale and mission.

I like Sean. He’s affable, doesn’t mind digging into the details of the church, and seems as inspired now, as a radical free-thinker, as he ever could have been the child of a cult leader. We talk about growing up in the cult. I couldn’t wait to ask him about the decrees.

“I haven’t talked to anyone about this in years,” he told me. It turns out, Sean is the one who recorded the “Rock ’n’ Roll Exposé #1” tape—the one that Seymour Glass and Ian and Don from Negativland found at local junk stores. The one that someone out there had released as Sounds of American Doomsday Cults, Vol 14. In the 80s, Sean had headed a 25-person team that made audio and video tapes to mail to devotees scattered around the world. The team cranked out tapes like “Rock ’n’ Roll Exposé” on a weekly basis.

“We produced more ‘commercial’ recordings of decrees that were meant for beginners,” Sean told me. “We duplicated tens of thousands of those. They were slow and clearly audible. The high speed version of the decree on this [Sounds of American Doomsday Cults] CD would have been from one of the smaller mailings, probably produced in a quantity of a few hundred copies.” He said the service documented on the CD was fairly ordinary—Elizabeth Prophet spent lots of time decrying rock music and leading decrees meant to destroy it.

I ask Sean what he thinks of the 27-minute decree—the one that first stunned me on the radio, the one that makes my neighbors peer curiously into my living room window, the one I fall asleep to sometimes. I confessed to him how much I enjoyed it. “If you had to listen to that for 20 years, you wouldn’t be so enamored of it,” he said flatly. “As a vocal novelty, it’s interesting.”

“But you’ve got to realize that a lot of people spent years of their lives thinking they would change the world with these sounds, and it was a massive waste of energy,” he continued. “There was a human toll taken based on these ideas. When you start to believe that intentions themselves can lead to a change, you’re lost. That’s what the decrees were about. And it sickens me to think people are still doing these. I can totally appreciate how this would be very interesting to avant garde and sound collages. But these were real people going down the wrong path. A lot of them, children [for example], against their will. It’s destructive. It’s not harmless.”

(The decrees aren’t gibberish, either, Sean reveals to me. A sample line no untrained ear would ever pick out: “O Hercules thy splendid shining, shatter failure and opining. Open the way in love divining, seal each one in crystal lining.”)

I know what Sean Prophet says is true, and in fact, it articulates something I’d been struggling with. It’s not just voyeuristic, listening to these old tapes—it’s tapping into a world I know nothing about, extracting a 27-minute sample, and burying myself in it like it’s any old experimental recording. There’s a world beyond the recording I’ll never grasp; a web of believers who were (and perhaps still are) enraptured, mislead, and manipulated. I feel in some way that it’s unfair to dig into the recording without fully appreciating its origins. It’s a door I’m not ready to open. But I can’t just stop my fascination with the tape, either.

I think back on the conversation I had with Mark Hosler of Negativland—a pioneer of this tape, in a weird way as much an expert as anyone. Hosler and other artists are able to appreciate these sounds as wholly independent—as much a product of the geeks who’ve dubbed it thousands of times as it is of a secluded doomsday cult in Montana.

“We have a true love and tender appreciation for all the weird things we have collaged in our work over the last 35 years, this tape included,” Hosler told me. “It’s never a patronizing or sneering or hateful thing, though perhaps some listeners mistakenly guess otherwise. It’s more like amazement and stunned admiration that humans being can be so incredibly odd and unusual.”

Chris Kissel is on Twitter – @chris_kissel