In 1993, Max Chappell, an obscure board game designer from San Diego, California, loaded his Plymouth Voyager minivan with a bunch of funky-looking chess sets and headed north. A Star Trek convention was being held at the Westin Bonaventure in downtown Los Angeles, and Chappell smelled an opportunity to hawk his singular creation, a 3D chess game called Hyperchess.

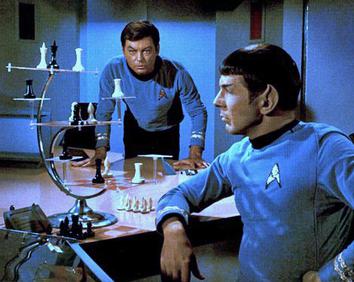

Hyperchess is a tale of two obsessions: one with chess, and the other with Star Trek. If one of these obsessions is more vital than the other, it would be Star Trek. To your average chess player, Hyperchess was just a weird chess game. But to a subset of Trekkies in the mid-90s, Hyperchess was a weird chess game that kind of looked like the iconic chess board from Star Trek: The Original Series.

Videos by VICE

“Star Trek fans just loved it,” Chappell, who is 69 years old, told me on the phone. “They thought that that my game was the original chess board that was on TV. But it wasn’t. It was actually a playable game.”

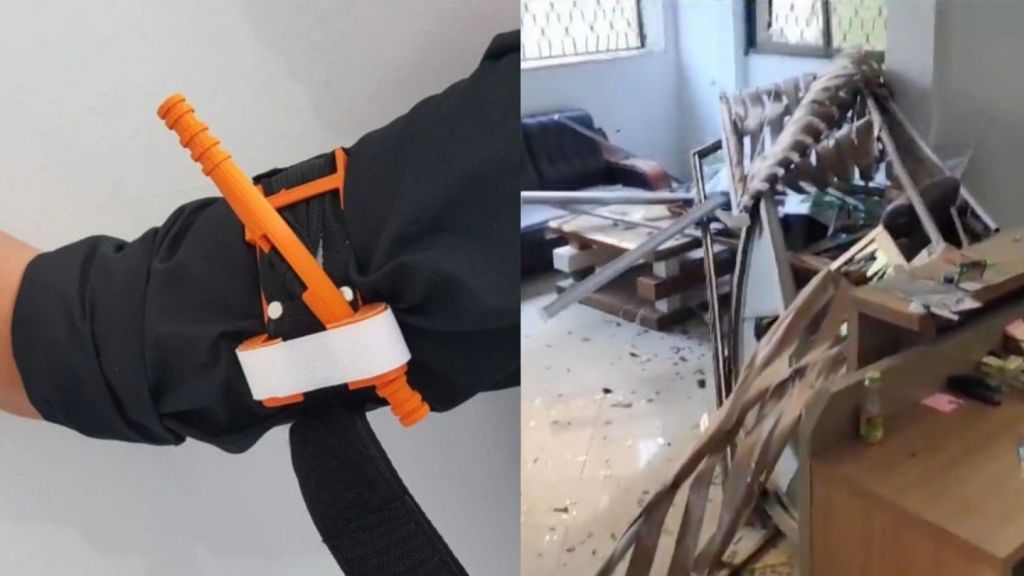

Much like Star Trek’s famed prop, Chappell’s chess boards were inscrutable. Looking at one is enough to make your head spin. While regular chess boards lay flat on a surface, Chappell’s chess boards stand at nearly three feet tall, with laser-cut surfaces of asymmetrical shapes staggered in a helical pattern around lamp rods. It resembles one of those multi-leveled cat condos, only with chess pieces perched on the platforms instead of sleeping felines.

Despite the strange appearance, Hyperchess is essentially chess with a Ferengi-sized wrinkle. Chappell, who spent a lifetime contemplating the game’s construction, designed the rules to stay true to its source material. As with vanilla chess, Hyperchess is a war of wits between two players who are both attempting to trap the opposing king.

“The unique feature is the rearrangement of the original 64 squares,” Chappell wrote in Hyperchess’s instruction manual. This rejiggered structure allowed the pieces to travel in all directions and, crucially, up and down. They could move in three dimensions.

The quest to free chess from the flatness of checkerboard is nothing new. Played on eight standard-sized chess boards stacked up like a double-decker sandwich, Raumschach (German for “space chess”) is considered the classic take on 3D chess, developed in 1907 by the occult scientist and Rosicrucian mystic Ferdinand Maack. With over 260 tweaks on the concept listed on The Chess Variant Pages website, there is no shortage of 3D chess clones. The only problem is that many of these games were never good.

“Most 3D chess games make no attempt to be faithful to the source, and some of them are quite superficial and worthless,” Dave Matson, the author of Exploring the Realm of Three-Dimensional Chess, told me in an email. “The inventors wanted their games to have some resemblance to chess, but the vast majority of them didn’t give it any deep thought.”

Chappell was enlightened to the woes of 3D chess at an early age. As a child, he showed great aptitude for chess, capable of beating students several grades ahead of him. But by the age of 13, he had grown bored with the standard rules. After class at Samuel Gompers Junior High School in El Cajon, California, he and his board game buddies began experimenting with a modified version of Raumschach that used three chess boards. (The origins of this game are unclear, but it was first documented in the 1968 edition of Chess Variations: Ancient, Regional, and Modern by John Gollon, and later marketed as Space Chess by a company called Chessex.)

The boys would place the boards on the table side by side, imagining that they were suspended in the air, one over the next. But no one ever seemed to win. The king could always escape. There were too many squares.

Squares consumed Chappell. Determined to come up with a version of 3D chess that was actually playable, he would sit in his bedroom at his parent’s house with a drafting board on his lap, dreaming of three-dimensional geometric shapes. He tried three boards but with fewer squares. He tried a 4 x 4 x 4 cube. He experimented with pyramids. But no matter the combination, they all played like crap.

“I was trying to make some type of cube. But when I saw the chess board on Star Trek, my way of thinking was totally changed,” Chappell said.

Star Trek’s 3D chess board was a lopsided, complicated-looking chess tower that could occasionally be seen sitting on a tables and countertops throughout in the USS Enterprise. The set first appeared in the original series’ pilot episode “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” with Spock on the verge of putting Kirk in a checkmate, and it lived on to become a Star Trek holy relic.

The first time Chappell laid eyes on the prop in the late 60s, he was transfixed by it. Suddenly, it occurred to him that a 3D chess didn’t have to be symmetrical. In fact, symmetry may have been a detriment. By shifting the boards out of alignment, the game could retain more of its natural cadence in vertical space.

Soon after, he set out to incorporate this unfamiliar concept into his designs. Unfortunately, Star Trek offered little other guidance. The show’s chess sets were constructed for the sake of looking modishly futuristic, with little logic behind the ornate setup.

“The show offered some very loose ideas for how to play, but clearly not enough to define real gameplay. Did pieces exist on more than one level? Could you drop straight down?” said Andrew Bartmess, a fellow 3D chess game designer, over email. In the 1970s, Bartmess authored a rule book called Tri-D Chess, designed to be played on a homemade replica of Star Trek’s chess board. His rules featured “attack boards,” or little chess elevators that could lift game pieces to other levels of the board, as was seen in the show.

Chappell hoped his version would maintain chess’s integrity, but coming up with a design was more complicated than you’d think. He spent approximately two decades hammering out the specifications of his invention. He was 22 when he jerry-rigged the first Hyperchess prototype from plywood and aluminum in his father’s garage, and 45 when he sold the first manufactured unit. In the years between, he did a lot of work on the game, redesigning the setup countless times, filing various patents, and trying in vain to remove bubbles from Formica laminate, which he planned to use to coat the transparent boards.

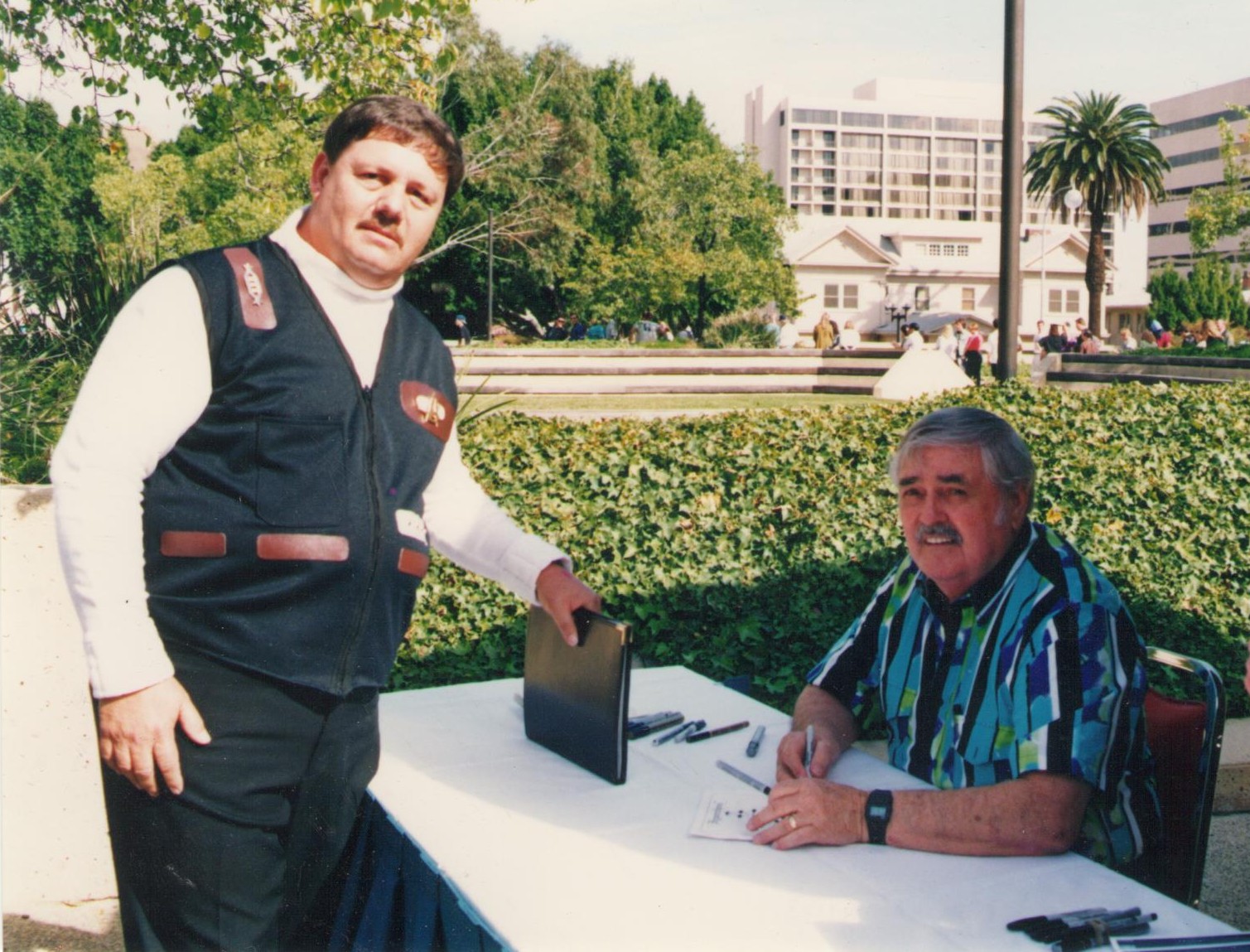

After 23 years of readjustments, Hyperchess was finally ready to be unveiled to the world. In 1993, on the first morning of the Star Trek convention at the Los Angeles Westin Bonaventure, Chappell set up a little booth with a folding table, scarlet banners, and two mutant chess boards. As he paced about his cramped booth space, waiting for the show to begin, his hands were clammy. The vendor’s area would soon be teeming with fans dressed in brightly-colored Starfleet uniforms.

“When some people see the board, they say, ‘Wow, cool—Let’s try that!’” said Nick Russell, who is currently developing a VR version of Hyperchess, over the phone. “But a little more often the reaction is, ‘I have no idea how I’d play this.’”

As it turned out, Trekkies were of the “Wow, cool!” variety. Over the three-day weekend, Chappell sold nearly $10,000 dollars worth of Hyperchess sets. Then, he returned to his garage to construct more. For the next five years, he would travel up and down the West Coast, hauling great big boxes of chess board pieces to nearly every Star Trek convention within driving distance. Initially, sales were brisk. Not even the 1994 release of Star Trek Tri-Dimensional Chess Set from Franklin—the officially licensed version of Star Trek chess, which borrowed from Bartmess’s Tri-D Chess rules—dampered demand.

“The Franklin Mint sets were way expensive and way dinky,” said Chappell. “Really, Tri-Dimensional Chess was not a playable game, even though some guy [Bartmess] wrote rules for it. My whole intention was to make it a playable game.”

But the audience for a well-playing, non-licensed knockoff of Star Trek chess proved self-limiting. He kept toting the boards to sci-fi conventions, but fewer people were interested. The price was dropped from $300 to $200. That didn’t really help. All around him, he saw an influx of unfamiliar alien species like Wookiees and Narns as Star Trek conventions broadened their appeal to include younger, hipper fandoms.

Eventually, he quit going to the conventions completely and opened an online shop, selling several boards a year until his GoDaddy domain expired a few years ago. Altogether, he’s sold around 450 boards, and is sitting on enough leftover inventory to build about 30 more. Despite the low numbers, he hasn’t given up.

Recently, supporters of Donald Trump have said the president is playing 3D chess, meaning his strategy is so advanced, his political opponents don’t even understand the complexity of the field they’re playing on. Ben Garrison, who describes himself as “drawing politically incorrect cartoons the mainstream media won’t run,” even imagined Trump as playing a game that looks a lot like Hyperchess against Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto. With so many pro-Trump pundits proclaiming that the President is playing 3D chess with his politics, weird chess variants are having something of a moment. Chappell’s eccentric dream to take chess where no man has gone before has never been more justified.