The users of Drugs Forum were intrigued. One Thursday in August of 2006, a man going by the name of Thirdedge logged onto the website that for more than 15 years has provided users of psychedelics with a place to share their experiences. Thirdedge had been experimenting with Spice – a new “legal high” marketed as an alternative to cannabis. “It seems to be the only one of these type of products that is really effective,” he wrote.

At the time, legal highs had a reputation for uselessness. In particular, the herbal blends sold as marijuana substitutes offered users little more than a possible placebo effect and a head rush from any tobacco with which they were smoked. Spice was different.

Videos by VICE

Thirdedge wanted answers. The listed ingredients on the packet – plants with names such as Blue Lotus, Indian Warrior, Dwarf Skullcap and Siberian Motherwort – were not previously known to produce psychedelic effects. Thirdedge proposed two theories. “One or a combination of the above ingredients is a DECENT cannabis alternative,” he wrote. “Alternatively the product could be mislabeled and contain something completely different?”

Such speculation did little to dampen enthusiasm for Spice. Positive reviews flooded in. One user said Spice was “even more trippy” and “lasted even longer” than marijuana. Another wrote: “Spice is like skunk without the bad bits.” It hardly seemed to matter that nobody knew why. All anyone knew for sure was that Spice worked.

It would be more than two years before researchers in Germany discovered the truth. The active ingredient in Spice was synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 – a chemical compound designed to replicate the effects of marijuana. Spice was no herbal high, but a potent new designer drug.

The authorities moved quickly to ban Spice, but their efforts did little to stop the drug’s spread. While some producers stopped trading, others had alternative compounds ready and waiting. A game of cat and mouse ensued, with manufacturers responding to each successive ban by launching new drugs that remained within the law. A pattern soon emerged, whereby the effects of the drugs became further and further removed from those of the original product.

Just over ten years since it first emerged, Spice is seen as one of the greatest drugs threats facing the UK. It has been described as a “blitzkrieg” upon the homeless population and is being linked to an increasing number of deaths. It is a major factor in a crisis engulfing the prison system. Drugs workers have described it as “worse than heroin”. In recent weeks, videos have emerged of users stood motionless in town and city centres, prompting tabloids to warn of a Spice epidemic and decry the terrifying effects of this so-called “zombie” drug.

WATCH – ‘Spice Boys – The Hard Lives of Britain’s Synthetic Marijuana Addicts’

It started with a ban. Rich Watson knew it was coming. The idea for his company, The Psyche Deli, had come to him at university when he discovered a loophole that meant it was legal to sell fresh magic mushrooms. “There were some obstacles in the way,” he told me recently, “but I realised it could actually be a big money spinner.”

Watson thought the loophole he’d identified looked watertight, but he wanted additional assurance. He wrote to the government department with responsibility for drugs policy, asking for clarification, expecting his idea to be immediately shut down. “One of the big hurdles was the Home Office,” he remembered thinking at the time. “Obviously they’re going to come up with a reason why I can’t.” In March of 2002, Watson received a reply: the sale of fresh magic mushrooms was perfectly legal. “It was one of those moments where it didn’t quite seem real,” he said.

Watson began importing mushrooms from Amsterdam and supplying head shops in the UK. Before long, he had recruited others to help. Richard Creswell grew mushrooms in a fish tank in his bedroom. Paul Galbraith became the company’s salesman, convincing head shops around the country to stock their product. Whenever the mushrooms were moved, drivers would carry photocopies of the Home Office letter in case they were stopped by the police.

“We sort of knew we would get one chance and probably get a year or two before they changed the law,” Watson told me. On the 29th of November, 2003, a friend called him to ask if he’d seen the papers. An image of the Psyche Deli’s mushrooms was splashed across the Guardian‘s front page. The paper informed its readers that the Psyche Deli was selling 5,000 “trips” a week via three market stalls in London and 30 head shops across the country.

The consequences were mixed. “We sold so many mushrooms,” said Watson. “Our stalls were just going through kilos and kilos of them.” But while the Psyche Deli had largely been left alone until then, as politicians realised that psychedelic drugs were being sold on the high street, a crackdown became inevitable. “It was the beginning of things going wrong,” said Watson.

In the months that followed, the government rowed back on its original advice. A number of mushroom retailers were arrested. Watson, who had been taking a backseat in the business for a while, decided to step down. “My parents had expectations of me working in a bank, not selling drugs, which is fair enough,” he told me, with a laugh. Creswell and Galbraith, who by now were partners in the business, decided to carry on.

Under their leadership, the Psyche Deli joined forces with the drugs legalisation movement to oppose the mushroom crackdown. In December of 2004, Galbraith told the Guardian: “We never set out to do anything illegal. We asked all the requisite authorities what we were able to do, and it looks like many other traders did the same. Over the past two years, although nothing has actually changed in the law, the Home Office’s interpretation appears to have changed.”

Determined to settle the matter conclusively, the government announced a ban on magic mushrooms in any form. Along with other sellers, the Psyche Deli established the Entheogen Defence Fund to challenge the move. Nevertheless, on the 18th of July, 2005, the ban came into force. A message was posted on the Psyche Deli’s website. “This was The Psyche Deli LLP… but now it’s all over and we’re shut,” it read. “We’ve got to find something to do with ourselves… We’re working to bring you ‘the next big [legal!] thing’.”

In January of 2006, the website was updated again. “The Psyche Deli remains committed to sourcing new and effective entheogenic products,” it read. “We are proud to introduce Spice, an impressive new herbal blend.”

“They are not simply substitutes – they act at some of the same brain sites as herbal cannabis. Some of these new compounds are about 30, even up to 500, times more potent.”

After the launch of Spice, for the Psyche Deli it was business as usual. Accounts were filed with Companies House. The business paid VAT. Its new product was sold through high street shops and online retailers.

Spice itself was slickly marketed and sold in distinctive foil packets. The name and logo appear to have been inspired by Melange, a fictional drug which featured in the Dune series of science fiction novels by Frank Herbert. In these novels, Melange was referred to as “the spice”, and caused the eyes of users to turn blue. (There are other similarities – Herbert is believed to have taken his own inspiration from experimenting with magic mushrooms.)

In April of 2007, the Psyche Deli trademarked the Spice logo, describing the product as “incense”. The application reflected the company’s official position – Spice packages were labelled “not for human consumption” to avoid regulations applied to medicines and food. A second application, filed six months after the first, revealed the true position when the logo was trademarked for products described as “herbs for smoking”.

It is unclear what the motives for hiding the true nature, and ingredients, of Spice might have been. Creswell and Galbraith declined to comment for this article. It seems likely that, given the Psyche Deli’s earlier experience with magic mushrooms, the decision was taken not to disclose the active ingredient in an attempt to postpone the inevitable crackdown.

If that was the tactic, it seems to have worked. Within a few months of Spice hitting the market, it came to the attention of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) through the network’s early warning system, which tracks data – including seizures by law enforcement agencies and hospital admissions – to identify new drugs.

Just as the drug’s users were intrigued as to the source of the its effects, so were researchers and law enforcement officials. Michael Evans-Brown, a scientific analyst in the action on new drugs team at the EMCDDA, told me recently: “The products were claiming that they were natural herbal blends and so on. Yet, when you looked at some of the reports on the internet, people were reporting cannabis-like effects having smoked them.”

On the 15th of December, 2008, researchers at German pharmaceutical company THC-Pharm made a discovery. The active and unlisted ingredient in Spice was named as JWH-018, a chemical compound created more than 20 years earlier by a university professor from South Carolina.

“The effect was just a slightly more chemically weed high. I was laughing at the time and thinking, ‘I can’t really see that going far.’”

John W Huffman never intended to revolutionise the recreational drugs market; he wanted to help develop new treatments for pain associated with conditions including cancer. Three years after graduating from Harvard in 1957 he took a job as an assistant professor at Clemson University, where he continued working for the next 50 years.

Huffman’s specialism was creating new cannabinoids – chemical compounds that act on the same brain receptors as THC, the psychoactive chemical present in cannabis. Like most researchers he published his findings in publicly available scientific journals, naming many of his compounds after his own initials. In doing so, he unknowingly created a set of instructions which would later be used to create a new wave of psychedelic drugs.

Watson told me that, during the magic mushroom boom, the Psyche Deli had been approached by “rogue chemists” seeking to bring new drugs to the recreational market. Most of these were judged to be unappealing or too risky for users. Watson remembers the first time he tried Spice, before the drug was launched to the public. “The effect was just a slightly more chemically weed high,” he said. “I was laughing at the time and thinking, ‘I can’t really see that going far.’”

Creswell and Galbraith, however, believed Spice had potential. Researchers tend to agree that, compared with the effects of the synthetic cannabinoids being sold today, the effects of the original Spice products were relatively mild, with harms roughly equivalent to herbal cannabis. In Huffman’s creation, the Psyche Deli found the balance between risk and reward it was looking for.

The rewards were sizeable. Between 2006 and 2007, accounts filed with Companies House reveal that the Psyche Deli’s assets rose from £65,000 to £899,000. However, just like magic mushrooms before it, Spice was an opportunity with a limited shelf life. Once it became clear that Spice was more than a herbal blend, European governments scrambled to ban the drug. By mid-2009, controls had been introduced in Austria, Germany, France, Luxembourg and Poland.

In December of 2009, Spice was one of a number of legal highs banned in the UK. The Psyche Deli, anticipating the change, had shut down its operations several months before. An email from a Spice wholesaler, posted to an online drugs forum at the time, suggested that remaining stocks had been sold to the Dutch head shop de Sjamaan. Today, the Spice trademarks are held by another Dutch company. Galbraith runs a catering company. Creswell is a wedding DJ.

John W. Huffman retired in 2010. Now in his eighties, he lives a reclusive life in the Smoky Mountains. Speaking to the Washington Post in 2015, Huffman recalled hearing about Spice shortly after the active ingredient was discovered. “I thought it was sort of hilarious at the time,” he said. “Then I started hearing about some of the bad results, and I thought, ‘Hmm, I guess someone opened Pandora’s box.’”

The term “synthetic cannabis” can be misleading. Harry Sumnall is a professor of substance abuse at the Public Health Institute. “They are not simply substitutes,” he told me. “They act at some of the same brain sites as herbal cannabis. Some of these new compounds are about 30, even up to 500, times more potent. We also know they have quite a complex pharmacology. They are probably acting on other brain sites that we don’t think herbal cannabis acts upon.”

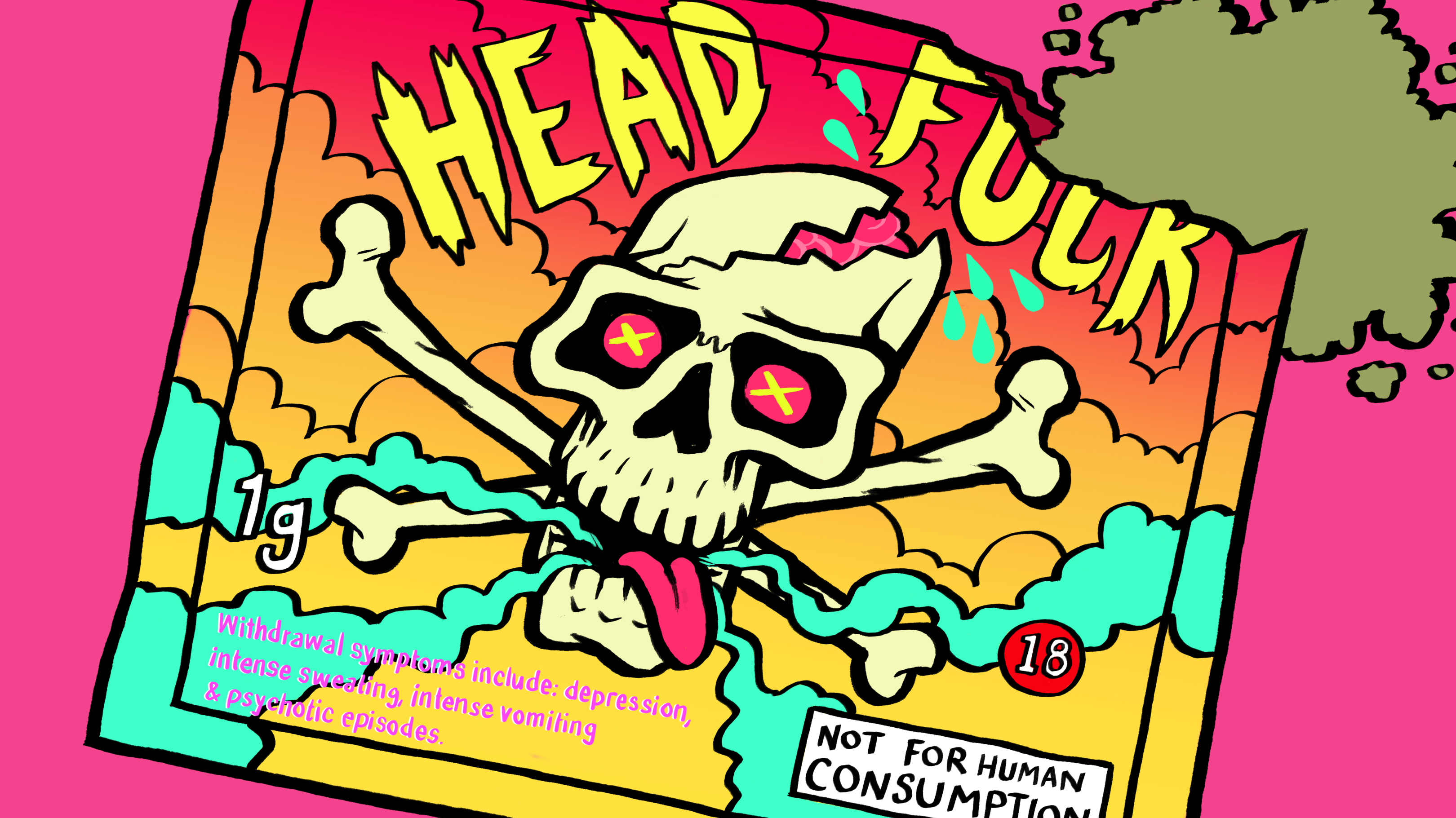

The drugs have also evolved. As supplies of Spice dwindled after the UK government ban, rival producers took over the market, with brands such as K2, Black Mamba and Yucatan Fire. Some contained the same active ingredient as Spice, but others were based on different compounds which remained legal. This second generation of synthetic cannabinoids was subject to a further ban in 2013. As before, producers adopted a new set of compounds and carried on.

Spice, which started out as a trademarked brand name, soon became a generic term for a bewildering array of brands and substances – many of which are far removed from the original product. The EMCDDA currently monitors 171 synthetic cannabinoids. Most are believed to be manufactured in China before being shipped to Europe, where they are mixed with plant material before being sold. The UN Office for Drugs and Crime has received reports of more than 240 different synthetic cannabinoids from more than 65 countries.

“There’s literally thousands of them that could potentially be synthesised,” said Sumnall. Many of these newer synthetic cannabinoids appear to be stronger and more unpredictable than their early iterations. “The market has adapted and what seems to have happened is more and more potent drugs emerge after each set of legislation,” said Sumnall.

Neil Whittaker, a former drug user in Sheffield who is now in recovery, was introduced to Spice around four years ago. At first, “it were like a powerful weed experience”, he told me. Over a period of a few months, Whittaker noticed the drug was having a different effect. “The Spice started to get more powerful,” he said. Whittaker would pass out, then wake up in public in strange positions on the floor. Eventually, he gave up Spice after turning to speed instead.

As the potency of Spice increased, many casual users stopped using the drug. But in prisons and among the homeless population, where Spice gained a foothold due to its low cost and a lack of effective drug testing, its popularity skyrocketed. Charities have estimated that, in some areas of the country, up to 90 percent of the homeless population use Spice. A 2016 report by offenders’ charity User Voice found that one in three prisoners had used the drug within the last month.

Increasingly, the market for Spice appears to be comprised of individuals seeking oblivion. Dr Henry Fisher, policy director at the drugs think tank Volte Face, told me: “If you’re trying to get through a cold night on the street and you want something that’s going to block out everything, it used to be you’d reach out for a K cider or Tennent’s Super. Now you reach for Spice.”

Screenshots from a video, filmed inside a British prison, of an inmate smoking Spice and collapsing. Via YouTube

In May of 2016, the Psychoactive Substances Act came into force in the UK. After attempts to legislate against individual legal highs had failed, the government was forced to take a different approach. The act placed a blanket ban on all psychoactive substances – with exemptions for alcohol, tobacco and caffeine. While possession remained legal, the act introduced a penalty of up to seven years in prison for supply.

Three months later, the government claimed victory. The Home Office announced that 186 suppliers had been arrested, 308 shops had stopped selling NPS and 24 had closed altogether. Government minister Sarah Newton said: “The Psychoactive Substances Act is sending out a clear message – this government will take whatever action is necessary to keep our families and communities safe.”

As the first anniversary of the legal highs ban approaches, the picture looks a lot more complex. While head shops and online retailers have stopped selling NPS, the supply chain is now under the control of criminal gangs. A 2016 EMCDDA report found there had been no slowdown in the number, type or availability of new psychoactive substances in Europe – with chemicals continuing to be imported from India and China. “Given the large profits and low risk of operating in this area, it is possible that criminal organisations will become even more active,” it added.

Rick Bradley is operations manager at drug treatment charity Addaction. I asked him for his verdict on the Psychoactive Substances Act. “There’s very little positive you can say around synthetic cannabinoid outcomes,” he said. “It’s the vulnerable populations who are still using and they don’t care whether or not they are using an illegal substance. It’s certainly not been a success story.” Nevertheless, efforts to tackle Spice continue to focus on criminal justice. Last December, possession of a third generation of synthetic cannabinoids was made a criminal offence. Recently, there have been calls to make Spice a class A drug.

In March of this year, footage emerged of Spice users standing lifeless in town and city centres across the UK. “Footage shows ‘Zombies’ after taking Spice in Manchester,” read a headline from the Daily Mail. “Spice drug zombies appear frozen in time,” read another from the Metro. The coverage lacked compassion, but it drew attention to a worsening problem on the streets. Julie Boyle, a support worker at Lifeshare, a charity that supports homeless people in Manchester, told me: “We’ve never had as many kick-offs, as many ambulance visits, as many police visits.”

Boyle highlighted another problem that had arisen since the Psychoactive Substances Act came into effect. Spice was now only available in unbranded baggies. While details of ingredients had always been unreliable, branded packaging at least provided an indication of the likely strength and effect. Now, users had been deprived any indication at all. “The ban made things worse, not better,” she said. “The issue we’ve got now is we don’t know what’s in it and we don’t really know who’s making it. It’s just getting worse and worse and worse.”

Synthetic cannabis being sold under various brand names (Photo: VICE)

Dr Oliver Sutcliffe held up a clear plastic vial containing a small amount of herbs submerged in a translucent green liquid. “One of the compounds in there will be the drug we want,” he said.

Sutcliffe was explaining the process involved in analysing Spice. He drew my attention to a computer monitor displaying a line graph with three peaks, each one smaller than the last. “The first is nicotine because it’s mixed with tobacco,” he said. The second peak indicated a sample compound injected as part of the analysis process. “This little peak at the end,” he said, pointing to the right hand side of the screen. “This is actually the synthetic cannabinoid. 5F-ADB.”

For the past six weeks, Sutcliffe, a senior lecturer in psychopharmaceutical chemistry at Manchester Metropolitan University, had been analysing samples seized by the police. From just 14 samples, Sutcliffe had found eight different synthetic cannabinoids. One of these compounds was linked to catatonic states among users in Brooklyn. 5F-ADB had been linked to ten deaths in Japan.

Sutcliffe’s analysis indicated a potency of six percent – strong, but well below the strongest he’d identified. In recent weeks, he’d discovered dramatic variations in the level of psychoactive chemicals present in each sample, ranging from two to 20 percent. It was unclear whether the variation was intentional or down to inconsistency in the manufacturing process – suppliers have been known to use cement mixers to bind the chemical compounds to plant material. I asked Sutcliffe what this meant for anyone taking these drugs. “It’s a shot in the dark,” he said.

It was late afternoon when I left Manchester Metropolitan University. As I walked through Piccadilly Gardens, where police had recently been called to 15 Spice-related incidents in the space of just a few minutes, I noticed a man sitting on a bench on the north side of the square. He looked to be in his mid-forties and was dressed in baggy black clothes, ingrained with the grime of the street. His eyes were closed, his chin tucked close against his chest. Occasionally his head jerked back as unconsciousness caused his body to fall forwards.

After about five minutes, the man opened his eyes, sat upright and looked at the purple lighter in his hand as if he was seeing it for the first time. From his jacket pocket, he retrieved a tiny stub of a roll-up and placed it between his lips. Slowly, he raised the lighter, sparked it, then inhaled.

More on VICE:

Two New Reports Have Revealed Just How Bad Britain’s Prison Drug Problem Has Got

Why the Government Is Directly Responsible for the Rise of Drug-Related Mental Health Issues

Inmates Talk About How Synthetic Cannabis Is Fucking Everyone Up in Prisons