For a few days in February, the blurb on the front page of Tommy Robinson’s website read “New Summer Menus Available Now”.

At the time, the former EDL leader had just announced his departure from Canadian alt-right outlet Rebel Media and was preparing to launch his website. Thanks to a glitch common to the website platform Squarespace, this sentence appeared as the homepage took shape, its message at odds with the dark hyperbole around it. Having encountered this glitch while building my own website, the anomaly is disconcertingly humanising: it’s a reminder that Robinson is bound to the same limited tools of the internet as any other online commentator, as he evolves from street protester to DIY social media personality, riding the populist wave of the alt-right movement.

Videos by VICE

During the years since his time in the EDL – the far-right street movement he founded – Robinson has rebranded himself repeatedly, and often clumsily. In October of 2013, a couple of months before he was jailed for mortgage fraud, he left the EDL with the support of the anti-extremism think-tank Quilliam. Then he abruptly gave up on anti-extremism with a short-lived stint heading up the UK branch of the European anti-Islam organisation Pegida. Then, towards the end of 2017, there was this mystifying turn as the goodwill ambassador of an unregistered arts charity.

The common link between most of these disparate activities has been Robinson’s anti-Islam rhetoric. His platform – that Islam is an inherently violent religion waging war on the way of life in the Christian West – has been honed as he grows in the public eye, but never abandoned or moderated. These views were widely accepted to have been formed during his youth in Luton, when the town was linked to activity by Islamist extremists Anjem Choudary and Sayful Islam. Robinson has also cited other factors, such as the 1995 murder of Mark Sharp and numerous locally-held grudges.

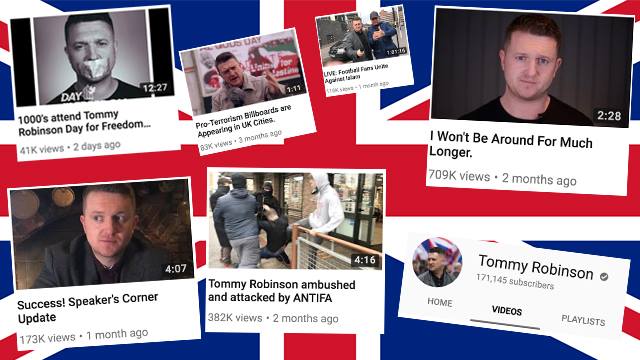

In his latest incarnation – as a sort of vigilante vlogger broadcasting via his personal YouTube account – he has gathered a significant follower base, whose growth has coincided with a period in which the UK has seen a rise in “explicit racial, ethnic and religious intolerance” as a result of the Brexit referendum, according to the recent findings of a UN expert. A prolific documenter of even the most banal encounters, Robinson can command up to millions of views for his dispatches, which might include anything from sneering at mosques from his car to filming without permission at the offices of people who have written about him in ways he doesn’t like. Since leaving Rebel Media, his videos have taken on a noticeably more paranoid tone. Unsurprising, perhaps, considering the tumultuous year he has had so far.

As 2018 began, his name was inextricably linked to the trial of Darren Osborne, the Finsbury Park mosque attacker. At the end of January, as the verdict was announced, journalists reported that Osborne had received messages from Robinson’s newsletter in the days ahead of the attack, and may have quoted Robinson indirectly in his note. Some of those journalists received threatening messages on social media, in several cases after Robinson tweeted their profile to his followers.

In March, Robinson was suspended from Twitter for violating its terms. He released a video of himself talking urgently into the camera. “I won’t be around for much longer,” he said, appealing to his followers for support. Then, on the 28th of March, he was permanently banned. The latest declaration on his website – “The truth has to be told. I can’t do it without you” – hinted at his next incarnation as a crusader, or even martyr, for free speech. He later spearheaded “Day for Freedom“, a march on Downing Street with other right-wing figures including Milo Yiannopoulos and Breitbart’s London editor Raheem Kassam.

As he finds his groove among a growing online community, Tommy Robinson is increasingly a presence in the intellectual culture of the far-right, while his rhetoric helps fuel a tide of growing Islamophobia in the West. He’s always argued that he’s not racist or far-right, saying he’s opposed not to Muslims, but rather Islam. However, his leadership of two far-right associated movements compromises his claims. His message, too, is undeniably complementary to far-right aims. One journalist told me, “I was making a film about Bulgarian fascists. What they watched on YouTube all day was [Infowars Editor-at-Large] Paul Joseph Watson, and Tommy Robinson, and other German equivalents.”

Such contradictions have been part of Robinson’s career from the beginning, set against the insistence that his version of the story is inarguable and obvious. From this culture of confusion – often mistaken for mystery – arises the questions people have always asked about him. What motivates him? What does he want to achieve?

To answer this, it may help to examine his origins.

Throughout Robinson’s various phases, one consistent thread has been his association with Luton, the town where he was raised.

It was in Luton that the EDL first emerged, with Robinson at its helm, borne from a protest group called United People of Luton. Here, the British far-right found a surprising new expression. Due to close relations between the communities who shared the layout of Luton’s estates, the EDL was tolerant of Irish Catholicism, and accepted minorities as members. This ethos has followed Robinson through each of his endeavours, allowing him to score points for his declared lack of racism.

The story of Robinson’s early life in Luton is easy to find. Born Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, he was raised by an Irish immigrant mother and a stepfather whose name he took. He attended Putteridge High School, where he says he witnessed gang activity divided along racial lines. His autobiography, Enemy of the State, includes detailed accounts of alleged gang fights. It also reveals personal grievances that include not being invited to the weddings of two Muslim friends, Kamram and Imram, with whom he bonded at school after they raised money to buy a Porsche together.

While Robinson’s old stomping grounds are found all over Luton, it is Luton Town FC that forms the heart of his story. In his book, Robinson hypothesises that the Muslim gangs that affected his teen years were formed in reaction to Luton Town football gangs. From a young age, Robinson was associated with the most notorious of these: the MIGs, or Men in Gear. Through the MIGs, he encountered the originator of his alias – a football hooligan who also used the moniker Tommy Robinson. He also developed a talent for disruption which would feed into his leadership of the EDL, though Robinson describes his dalliances with hooliganism – as well as a brief stint as a BNP member in 2004 – as youthful missteps.

In Luton, stories about Robinson tend to revolve around football. One resident tells me that he often sees “Yaxley, or whatever his real name is” at the football ground with his family, sometimes sitting with Asian families. He has suspicions that Robinson doesn’t really believe the things he says in public, and doesn’t understand why he does it. In a phone interview, Robinson says that this story only confirms that he is not racist or anti-Muslim.

Outside the grounds on Kenilworth Road, a man called Jonny tells me he does know why. “He’s making money,” he says, annoyed. “One of my mates stopped him once and said, ‘Oi, you prick, what you doing all this for?’ and he said, ‘Mate, I’m not doing this for no hate bullshit, I’m making money.’ I bet he’s made millions out of this EDL bullshit.” In response, Robinson says this is “hilarious”, and that he has been in financial “hell” over the years due to the EDL, a situation that improved only after the publication of his two books.

What people in Luton say about Robinson can be wildly speculative, but it does illustrate his position in the community and how intricately his history is linked with the town’s. In Bury Park, where Luton Town FC is located, and which Robinson calls “a Muslim enclave”, a local activist called Shaz Zaman tells me that most Lutonians will have a story about Robinson. He says you can’t believe them, just as you can’t believe everything Robinson says about Luton.

Zaman is in the business of de-escalation. As we walk, he helps me dispel some of the claims about the area that Robinson made in Enemy of the State. He points out churches as evidence for religious diversity in the community, and takes us past Denbigh High School, which Robinson falsely described as “100 percent Muslim”.

Zaman’s organisation, Luton Tigers, has its offices near Luton FC. He speaks in schools to counter the radicalisation of local youths. Meanwhile, Luton Town FC’s Daniel Douglas uses football to create a sense of community through the initiative Football for Peace. The successes of such organisations offer a significant challenge to Robinson’s brand. Five years after the EDL, community cohesion is a hot topic in the formerly divided town. Even Robinson’s uncle, an ex-EDL-member called Darren Carroll, now campaigns for tolerance in the local community.

The influence of the EDL has even faded in its former stronghold. In Farley Hill, the traditionally Irish Catholic estate that Robinson spent time in, I meet Dan. He was a patron of now-shuttered pub The Parrot, Tommy’s former local and a major EDL meeting place. “Tommy Robinson is a wrong-un,” he tells me. “He makes Luton look bad.”

Dan might once have fit the profile of an EDL member. He is young, white, drank in The Parrot, and wears Stone Island – a brand Robinson used to sell on the side. But he says that back when The Parrot was open and the EDL was still going, he had a problem with Robinson using it, as did many of the regulars.

To Dan, Robinson is not a Farley Hill boy. Dan does not even consider him working class, as he believes Robinson grew up comfortably, thanks to his stepfather’s plumbing business. He doesn’t live in Luton anymore, Dan has heard, he’s left for Milton Keynes. Robinson doesn’t confirm where he lives, but dismisses what he sees as pointless hearsay. After ten years in the public eye, he says, he’s used to people telling stories about him.

Those ten years didn’t just put Robinson in the spotlight. As his reputation spread, ordinary Lutonians were forced to explain themselves repeatedly to the media. As a result, canvassing opinions around the town can be a little eerie. It’s as though the whole population has been media-trained and prepared for the arrival of any visiting journalists. There is a pleasing symmetry in this – just as Robinson’s ideology was formed on Luton’s streets, it is now being debated and challenged there. As a result, Lutonians can seem unusually adept in challenging his logic, such as in this livestream, where two passersby, drawn into a debate about the Quran as they pass him on the high street, are able to do so in a calm and prepared manner. This also challenges one of Robinson’s most repeated claims – that wherever he goes, people agree with him.

You have to wonder if he, the original Luton lad, is affected by this ideological split from his hometown, as it casts off associations that he can’t.

Mark, a journalist who worked closely with Robinson, says, “The key thing to remember is that Tommy has a profile from a movement he’s embarrassed of.” He adds that Robinson did not socialise with other members of the EDL in Luton, but preferred nights out in Essex with non-political friends. Robinson says that he wasn’t embarrassed by the EDL, but is embarrassed by what they’ve become – and agrees that he prefers socialising with his friends to anyone else.

“The sense I got from the Tommy that I knew was that he craved approval,” says Mark. “He craves limelight. He has always had this sense that he’s smart.”

Mark thinks that much of Robinson’s ideology derives directly from local beefs, played out around the football ground when he was a teenager. It’s possible that one of these local beefs casts doubt on a major part of Robinson’s origin story – that he saw white women being “brainwashed” by Muslims around Luton.

“All the heroin in Luton happened to be run by Pakistani boys,” says Mark. “All those boys were secular, and Tommy liked them, was friends with them. He moved in a lot of circles, was a key football boy, key lad from the estates. What happened is that the boys running the drugs got fast cars, nice apartments, picked up a lot of the girls from school, then those girls converted and put a hijab on. Tommy calls it brainwashing, but it’s a lot more normal than that. They fell in love.”

Robinson describes this as “mostly nonsense”.

“Some of the girls would fall in love,” he says. “Then slowly their whole life changes. They’re not allowed to hang out with certain friends, not allowed to wear certain clothes. Their mums and dads haven’t seen them for five years. That’s the brainwashing part.”

To Mark, Robinson is an ideologue. His persona is the result of long-held personal grudges, mixed up with a need for acceptance (Mark recalls an event when he seemed close to tears at being misunderstood). He also thinks Robinson’s views are exacerbated by a “toxic mess of conspiracy theories”, strengthened by his alliances with peers such as Infowars’ Alex Jones. These networks help Robinson’s ideas to spread all over the world, though Robinson himself cannot always follow.

Banned from the US for his criminal record, he is unable to exploit his profile there. In America, he might gain access to lucrative opportunities, like his contemporary Yiannopoulos has. It must be a source of frustration – however, it does feed neatly into the sense of injustice that galvanises his followers. Robinson’s journey from grassroots to new media has been fuelled by this, in particular by anger towards the mainstream media for ignoring his views.

Robinson is right to sometimes be defensive. He is, as some journalists have described him, a “pariah” figure to many in British society. However, he has been given fair opportunities to speak by the media. He has appeared on major news programmes like Newsnight (later describing Jeremy Paxman as “very fair”) and Andrew Neil’s Sunday Politics. A 2015 Huffington Post interview presented him as a family man with an alter-ego, and last year the Spectator columnist James Delingpole wrote, “Yes, I do like him.”

Mark says, “Tommy’s most effective shtick is one that right-wingers use constantly – along the lines of, ‘You liberals in your inner cities don’t understand,’ and some journalists lap this up. He’s saying, ‘I’m the working class boy from the wrong side of the tracks, telling the truth about Islam that politically-correct people don’t want to hear.’”

This ability to brand himself is Robinson’s particular strength. The historian Tom Holland, who appeared on the BBC’s When Tommy Met Mo, says, “There are loads and loads of people who hate Islam and shout on Twitter, and whoever hears of them? It’s the same as radical Muslims – it was Anjem Choudary who became their voice. Both of them are very talented, smart people, who have the charisma that enables them to become the lightning rod.”

Julia Ebner, author of The Rage: The Vicious Cycle of Islamist and Far-right Extremism, and a target of one of Robinson’s videos, says, “By utilising new media to get a bigger audience, he forces journalists to pay attention to him. It’s quite clever, to use this parallel ecosystem and online world until the point the media has to engage. He has a step-by-step strategy where he is careful and exploits particular moments. In the days after terrorist attacks, he is the first to shape the narrative to use this critical point for many people, when they are vulnerable and susceptible to adopting new ideologies.”

Ebner is still regularly threatened online as a result of her encounter with Robinson. But she says she feels empathy for him. Like Mark, she sensed that he was hurt by her inability to share his point of view. His book seems to her like a document of how someone might become radicalised. “His is a sad story in some ways,” she says. “In a different situation, it could have been turned into positive initiatives, this energy. The problem is he transformed it into something that could potentially harm our communities, and our inter-societal solidarity.”

Still, he is no idealist to her. “I’d rather say he’s an opportunist,” she says. “What matters most to him is about being talked about, being in the centre of the media, being lionised by his support base, making people listen by giving them what they want. That’s why he left Rebel Media. Without the paywall he has this reach that allows him to mainstream his ideas.”

Robinson maintains that his motives are simple. “It’s quite obvious to anybody that I believe what I’m saying and what I’m doing,” he says. “It wouldn’t be worth the hassle otherwise, or the chaos that has come with it.” Chaos, you could argue, that has not just affected him, but Luton and the wider world.

It is not impossible to imagine a future where Robinson has become normalised, or even integrated into mainstream politics. While distant, it should be a frightening thought. Despite everything that he maintains, there is no denying the danger inherent in such quotes as “Islam is not a religion of peace” or “Hitler had nothing on Mohammed” on society as a whole, and on disturbed individuals like Darren Osborne.

Robinson has said that he is “insulted” by associations with Darren Osborne. During a Newsnight interview with Kirsty Wark, when Wark asked if he thought tweets of his read by Osborne were examples of hate speech, he described her line of questioning as “unbelievable”, adding that viewers turned to him because she was failing to deliver them “the truth”.

Watching this, I think of how Mark told me, “It’s probably pointless to engage in an argument with Tommy.” The problem for Britain – and increasingly the world – is that he won’t give us a choice.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Media Production/Getty Images -

Kari Keone (photo: @spaceghostkari / Instagram) -

Abstract Aerial Art/Getty Images