This article originally appeared on Noisey UK.

I was 14 when I bought my first record on vinyl. Actually, it was several records—and a total accident. I ordered a box set of Bright Eyes albums off Amazon, assuming it was a CD bundle, and what I got was the first five LPs and no idea how to play them. So my version of “the talk” was my parents sitting me down after school and explaining how the hell a turntable worked.

Videos by VICE

Dusting off the same boxy record player he got as a teenager and had been keeping in my nan’s garage—a turntable so old we had to be careful with the needle because they were out of production—my dad proudly played me some of his records: Black Sabbath, Kate Bush, and Thin Lizzy. The moment is hyped in my memory as being just like the opening scene of Almost Famous: a candle burning, Tommy revolving, not just hearing but experiencing the crackle and pop of dust on the needle, like a roaring fire in your ears. In reality, I probably dished out an adolescent catchphrase like, “Yeah, cool,” and shut my dad out of the room.

From then on, I near sacked off CDs. I’d listen to compilations of fart-in-a-trash-can mp3’s I’d downloaded from Limewire by day and records by night. I started collecting my own, but only the stuff I really cared about—the special stuff. Limited runs from Painkiller, a live box set of Animal Collective’s earliest and strangest releases (that I’ve since tried to sell on eBay twice in dire straits and have never been able to part with), and specific color variants from Orchid Tapes, who ship all their orders with sweets and tea and other assorted trinkets. Over the last few years, the “vinyl revival” has caused my collection to swell like The Rock’s biceps, as more and more bands have the scope to set their efforts to wax. But that revival has also found a cave full of glutinous ways to shit all over it. What was once a quiet world of treasures is becoming a commercial minefield.

Last week, the BPI released a report that suggested it is increased streaming and the vinyl revival that, together, kept the British music industry buoyant in 2015 by not just reaching the projected amount of vinyl sales, but jumping to 2.1 million. At face value it’s a good thing. For the first time since the dawn of Napster there is a spike in the number of young people voluntarily paying actual money for music on a format they can hold in their hands (which is nothing short of a small miracle). That would be exciting if it meant that the industry was flourishing for everybody, but at the moment it’s just not the case.

I’d like to say this spike in sales speaks to our growth as a generation, but when you consider that most of these records are coming from places like Urban Outfitters flogging copies of (What’s The Story) Morning Glory? for £30, it probably says less about our listening habits than it does about our penchant for old shit, which anybody who has ordered a drink in a bar recently and had it served to them in a mason jar will already know. Of those 2.1 million record sales, how many were for new albums released within the last 12 months? The answer, ultimately, is: not loads.

The best-selling vinyl albums in the UK of 2015 as of July included: Jamie xx’s In Colour, The Arctic Monkey’s AM, and Royal Blood’s debut, so you can’t say young people aren’t trying to hold it down for their generation. But the real-best sellers were The Stone Roses self-titled, Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti, and Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of The Moon. Because for every new release (from an independent label/artist or otherwise), a major will mine their archive and churn out 20 reissues, box sets and “deluxe editions”—a phrase that’s become so dirty it’s basically “The Scottish Play” of the music world. I’m not saying all reissues are bad news, but by and large the current wave of re-releasing that’s capitalizing on this opening in the vinyl market is in turn hurting the indie labels that got the revival going in the first place.

Lots of #rare finds on Urban Outfitters.com

For example, news broke last week that Sonic Youth’s Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, A Thousand Leaves, and NYC Ghosts & Flowers will be given the reissue treatment later this month, with Murray Street, Sonic Nurse, and Rather Ripped set to follow. Sonic Youth have been on an indefinite and likely everlasting hiatus since Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore split in 2011—and have been steadily reissuing their pre-Geffen catalogue ever since. Daydream Nation, The Whitey Album (released as Ciccone Youth), Bad Moon Rising, and EVOL have already been reissued through the band’s own label, which made sense both for them and their fans. Plus there were some extra goodies in the form of bonus tracks (even if they did come on a download card) for all the grunge stans out there.

But if you look at the newest batch of reprints, there is something decidedly jaded and cynical about them. For a start, they’re coming from a company called Union Square Music. USM are one of the UK’s leading reissue and compilations specialists, whose self-proclaimed highlights include The Very Best Of Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Greatest Ever Driving Songs, and Simply Salsa. That’s USM, not Sub Pop, SST, Interscope, Matador or any of the other labels Sonic Youth’s early material was released through. In fact, the newest vinyl reprints are for all their full-length albums released between 1994 and 2006 (save for 1995’s Washing Machine), also known as The Geffen Years.

While there’s nothing sinful about wanting a copy of one of those records regardless of how much it costs or whose pocket it ends up in, the fact remains that they were all major label releases and as such there are still so, so many copies in circulation already. You only need to turn to eBay, Discogs, any respectable record store or even some charity shops to find one. All most major label re-issues do is help raise the price of records in general due to rapid sales increases—which end up bottlenecking the production of vinyl, overwhelming retailers, and pushing back release dates for smaller labels who are deemed less of a priority. It stands to reason that the slower a label’s turnaround, the less they can actually release, which in turn affects their artists and ultimately their survival.

“When winter/spring comes around manufacturing times at pressing plants for labels like ours start to get significantly delayed as we get pushed to the back of queue behind represses of catalogue records,” Dany of Cork-based indie label Art for Blind told me back in 2014 during an investigation into Record Store Day’s effect on small labels. “At the moment we can’t afford to pay for a record that won’t be back from the plant for ten weeks as we need to get selling that record as close to the point where we pay for it as possible.” Similarly, Warren Hildebrand of Orchid Tapes—who were the first to release Alex G’s DSU—and Dave Benton of Double Double Whammy expressed frustrations over not getting their orders back on time. But, as far as the interests of those actually benefiting from the vinyl revival are concerned, that bedroom pop LP can wait. After all, there are reissues of the much sought after Inside In/Inside Out by The Kooks to be getting on with (out January 22, guys).

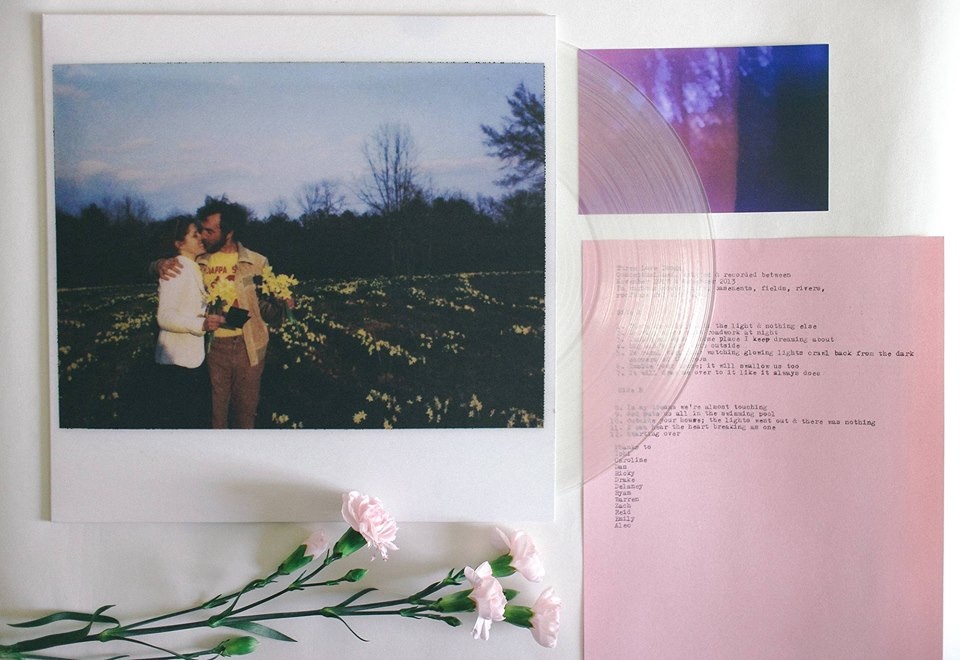

Ricky Eat Acid’s Three Love Songs, from Orchid Tapes

Obviously it goes without saying that not all reissues and anniversary editions are trash: Plenty of worthwhile albums have been given considerate reissue treatment. When Nas celebrated 20 years of Illmatic he gifted fans a reissue that included remixes, freestyles and unheard material. He re-toured the album from start to finish and put out a documentary exploring the making of Illmatic on a deeper level. As Noisey editor Joe Zadeh wrote, “It was like the entire album breathed again for a whole year.” What sucks is when reissue plants and majors pump out hundreds of thousands more copies of beloved albums that are already in wide circulation, capitalizing on the increased sentimentality around physical products so you’ll drop a week’s worth of lunches on something you could find for a fiver in an Oxfam bin—and be infinitely more gassed about.

True, not everybody likes to spend their time and money rummaging around second-hand shops for arms full of novelty tat, like a HIM seven-inch that comes in a black velvet sleeve or a picture disc of Bruce Willis’ Secret Agent Man. True, many people don’t give a shit about which particular pressing they have and just want to own the bloody record. There’s nothing wrong with any of that. What is wrong, though, is that the indie labels who have fostered the format while major label attention waned are now paying the price for the rejuvinated interest, struggling to keep afloat while their money is tied up for as long as ten months thanks to manufacturing delays because someone in a boardroom somewhere decided it was time to churn out yet another 200,000 copies of Revolver.

Although the rise in demand for vinyl has risen dramatically, the number of active pressing plants has stayed relatively static. The amount of people trained in electroplating (the process of making a mold from a lacquer) is even less, and if that wasn’t bad enough there are only two companies in the world still making vinyl record lacquer and one is an elderly Japanese man doing it in his garage. If the vinyl revival is here to stay, then we’re going to need a lot more people who can actually manufacture the records to support it, which is better than the alternative. After all, the backup at the plants signifies that there is demand for more records, not fewer, but the industry needs to expand to accomodate everyone. Those who buy from independent record labels like Art for Blind, Orchid Tapes, and Double Double Whammy do so because of the care that goes into their releases—the kind of care that’s absent from a 140g black disc stuck in a cardboard square that costs £25 from Tesco. Both are valid things to buy in theory, but when one is a fleeting interest that comes at the expense of the other, it’s hard not to be frustrated.

Perhaps nobody wants to hear a twenty-something wax lyrical about the soulful benefits of getting on your knees in a second-hand shop and rummaging through hundreds of dusty LPs in order to build your record collection. Perhaps nobody wants to hear a eulogy for the euphoria of finding a true #rarity priced at about a hundredth of its value in a local charity shop either, even if it is like coming up in a bubble bath. But for people who collect records for reasons beyond physical ownership, the revival is sucking all the joy out of it.

Follow Emma on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

KMazur/WireImage/Getty Images -

Axelle/Bauer-Griffin/FilmMagic/Getty Images -

Image: Shaun Cichacki