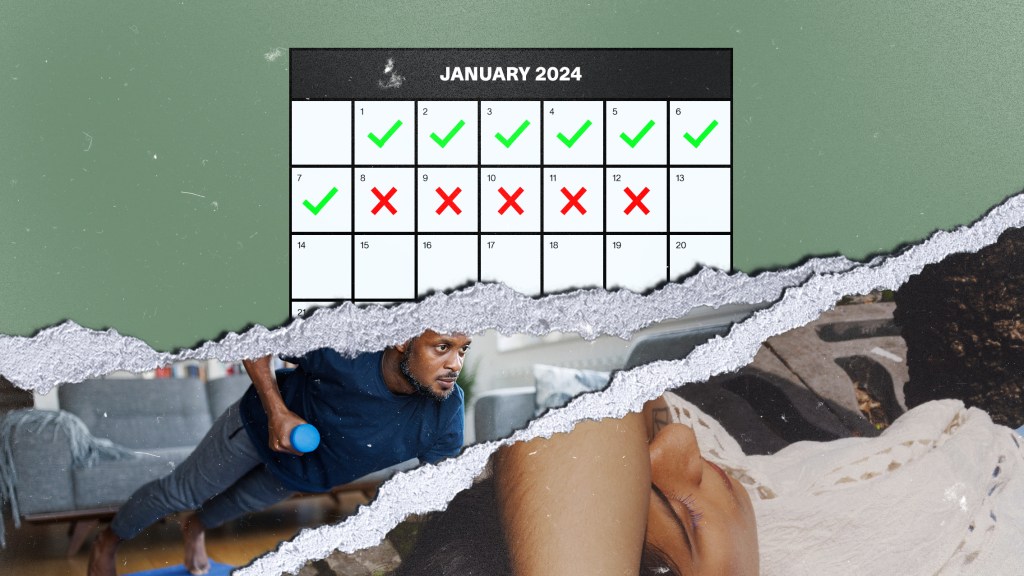

Lots of people avoid cardio when they’re trying to get fit—partly because they don’t like it, and partly because they’re worried it’ll make their muscles shrink and kill their gains. But are they right? How much cardio should you do—if any—when you’re trying to build muscle? And how much is too much?

Let’s cut to the chase: Cardio can put the brakes on muscle growth. It can do so by interfering with recovery between bouts of weight training, or leave you fatigued before you start lifting weights. This in turn compromises the “quality” of your workout, which reduces the strength of the muscle-building stimulus it generates.

Videos by VICE

Cardio can also turn down the volume on the “make me bigger” signals sent to muscle fibers in the hours and days after training. While the potential exists for cardio to dampen muscle growth, however, the extent to which it does so depends a lot on how much of it you’re doing, how hard it is, and when you’re doing it.

Research on this connection dates back to the 1970s, when a powerlifter by the name of Robert Hickson decided to join his boss, professor John Holloszy—the father of endurance exercise research—for a regular afternoon run. Hickson soon found that he was getting weaker and losing muscle, despite the fact he was still following his regular strength training program. So he decided to run an experiment to find out what was going on.

Published in 1980, Hickson’s study trained three groups of subjects: The first group lifted weights, while the second group went cycling and running. The subjects in the third group combined cardio and weight training.

In the strength-only group, leg strength increased at a consistent rate throughout the 10-week training program. In contrast, subjects who combined weight training and cardio saw their strength gains level off between weeks seven and eight. In weeks nine and ten, they actually got weaker.

When others replicated Hickson’s study, they found similar results. Training for both strength and endurance—termed concurrent training—led to reduced gains in strength and size, a phenomenon dubbed the “interference effect.”

Does this mean you should ditch cardio altogether if you want to gain muscle as fast as humanly possible? No it doesn’t, and here’s why: First, Hickson had his subjects lift weights five days a week and go running or cycling six days a week. That’s far more training than most people are doing. And even then, the interference effect didn’t show up until seven weeks into the study.

In other words, the effect that cardio has on your gains will depend on how much of it you’re doing. Lifting weights five days a week and doing cardio six times a week will make it very difficult to recover properly between bouts of weight training. Two hours of cardio a week, on the other hand—provided it’s not all done at a high intensity—is unlikely to pose a problem.

The extent to which cardio interferes with your progress is also, for the most part, body part specific. Doing high-intensity interval training (HIIT) before lifting weights, for example, has been shown to interfere with size and strength gains in the lower body. But it didn’t hamper gains in the upper body.

More from Tonic:

You also need to consider the length of time between cardio and weight training. On one end of the spectrum, you can do cardio and weights back to back, with little or no gap between the two. Or you can go to the other extreme, and do them on separate days. Which approach works best?

In most cases, you’re better off keeping cardio and weights separate. Inserting a sufficient length of time between the two can limit the extent to which cardio interferes with your gains. When two US researchers looked at the research on concurrent training, they came to the conclusion that, in an ideal world, cardio and weights should be separated by anywhere between six and 24 hours.

However, I don’t live in an ideal world, and neither do you. It might be the case that the only time you can fit in cardio is to do it before or after you lift weights. If so, what should come first, cardio or weights? Probably the worst option is to do cardio right before you lift. A bout of interval training performed immediately before strength training, for example, has been shown to blunt gains in muscle mass.

Five or ten minutes of gentle warming up on the bike, treadmill, or rowing machine is fine. But a tough cardio session is going to leave you fatigued before you even start lifting weights, which in turn is going to make it harder to do the work necessary to stimulate muscle growth. You’re not going to be able to get an effective workout in. Instead, do cardio after you’re done with the heavy lifting.

As far as the type of cardio is concerned, running isn’t the best option. Research shows that it’s much more likely to impede recovery and interfere with your gains. Instead, choose something low impact like rowing, incline treadmill walking, swimming, or cycling.

Cycling, in fact, may be the ideal companion to resistance training. In one study, adding 30-60 minutes of cycling twice a week to a two-day strength training program had no negative effect on gains in muscle size or strength. The thigh muscles grew at a similar rate in both the strength-only and strength plus cardio groups.

More interesting still, there is some research to hint at the possibility of a faster rate of muscle growth with cycling and resistance training compared with resistance training alone.

Granted, the research was done on strength training newbies, where virtually any stimulus will stimulate growth. And the total amount of training they did was relatively low. But at the very least, the findings do suggest that concerns about cardio interfering with muscle growth—provided your training program is set up properly—are overblown.

You also need to factor in the number of times you’ve traveled around the sun: Things you could get away with in your twenties are going to have a much bigger impact on your results at the age of 40 or 50.

In one study, a group of triathletes in their fifties recovered more slowly than triathletes in their twenties in the days following a 30-minute downhill run. The synthesis of new muscle protein was reduced, contributing to a slower rate of muscle repair. There was also a trend for masters triathletes to turn in a slower time trial performance than their younger counterparts ten hours after the run.

As you get older, the resources in your “recovery account” become increasingly scarce, and you’ll need to be a lot more careful about how they’re allocated. As long as you don’t go overboard on the volume, frequency, and intensity of your workouts, however, there’s no need to worry about cardio dramatically slowing down muscle growth.

Some types of cardio, in fact—cycling at a low-to-moderate intensity for 20-30 minutes the day after a heavy leg workout, for example—may even help recovery by promoting blood flow to the muscles without causing further damage.

There’s no rigid protocol that lays out exactly how much cardio you should do and when you should do it. But two to three cardio sessions a week, with each workout capped at around 45 minutes, is unlikely to damage your muscle-building efforts in the gym. As with most things, it’s the dose that makes the poison.

Christian Finn is a UK-based personal trainer and exercise scientist. He writes frequently about fitness and nutrition on his personal site, MuscleEvo.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of Tonic delivered to your inbox.