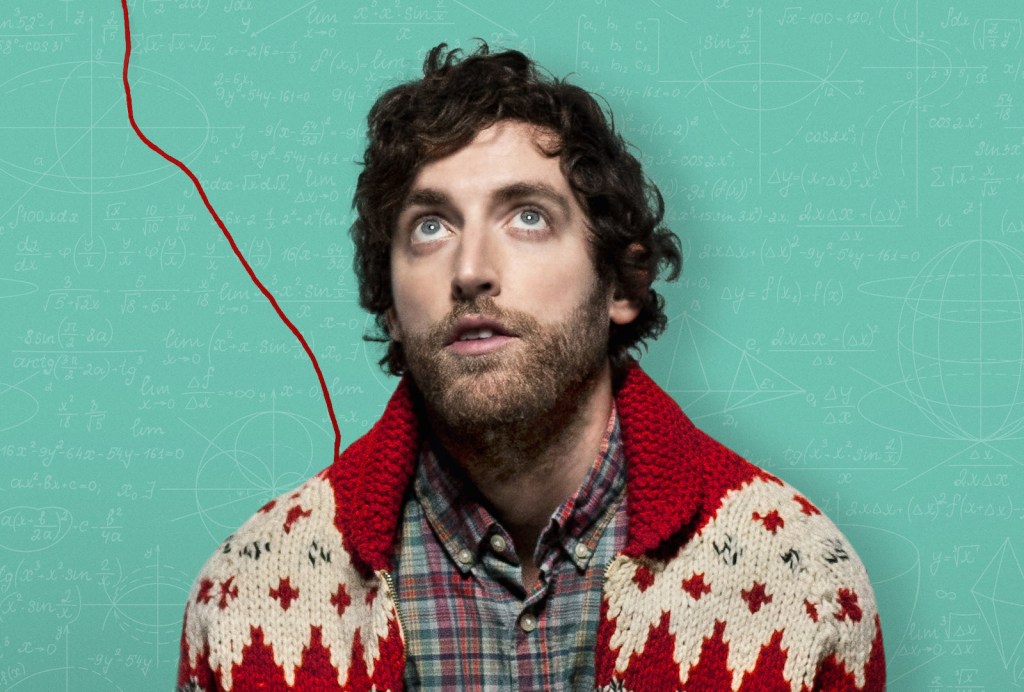

In Early Works, we talk to artists young and old about the jobs and life experiences that led them to their current moment. Today, it’s actor and comedian Thomas Middleditch, who stars in the just-released romantic dramedy Entanglement. (You’ve seen him in Silicon Valley too, obviously—as well as those ubiquitous Verizon commercials.)

This probably isn’t a huge shocker, but I was an odd duck growing up. I had a lot of alone time—not many friends, a fair amount of teasing and bullying. I always said that if I ever win an award, one of the first people I’ll thank is my drama teachers. We have this thing in Canada called Drama Fest—it’s basically theater sports, but you compete with your plays. You do regionals, provincials, and then nationals. It’s a really life-changing experience—a super supportive middle school bunch, so they’re screaming if there’s anything reasonably funny. I was like, The power I have!

Videos by VICE

My high school drama teacher Kim Wilson changed my life. He had an improv team—short-form, very rudimentary, both supervisors started in college. As someone who grew up in a small Canadian town, I was very fortunate it was Nelson. It’s a strong artist city, very hippie and LGBTQ-friendly. It’s a special place, and I was very fortunate that I had an invested drama teacher and local theater community that allowed a freak like me to find its place.

Improv and theater obviously gave me this focus, and I latched onto it, saying, “This is what I’m going to do forever.” Also, even though I started eighth grade as an outcast, the word got out that I was funny. Now, I was the class clown, and I ended up being pals with all the kids that had been bullying me for years. At that age, you don’t care—you’re willing to let all that shit slide. Whatever man, just accept me. Just make this pain end.

From that point on, not only did I have actually friends, but I had friends from a lot of different social groups. I was approachable—even if people didn’t know what to talk to me about, we could goof around, and I’d do something stupid to make them laugh. I’ll have you know, sir, that in high school we voted for valedictorian—it was a popularity contest. Guess who won? What a Cinderella story.

I dropped out of University of Victoria to go to George Brown in Toronto, which has a more robust theater program in Toronto. In the summer between being accepted at University of Victoria and starting there, I met people who were just doing sketch comedy, and I was like, Wait, you can just go do that? Easy decision, that was that. I loved Kids in the Hall, and I either wanted to be in Kids in the Hall or make my own Kids in the Hall. You’re in rural Canada, you talk to the guidance counselor, and you’re like, “I want to be on TV,” and they’re like, “First, get your degree.”

I thought of myself as a budding thespian, but over the course of theater training, I realized that it maybe wasn’t for me. You can’t improv in theater—and I’ll never stop doing improv. I’m a cynic—you have to have a little bit of cynicism to be a comedian—and it’s almost too ridiculous for me to take improv so earnestly. Good theater is good theater, but it wasn’t the most efficient way for someone who was trying to figure out how to do comedy.

People always want to know the algorithm for success. “What did you do? What can I replicate? What’s the math involved?” My rebuttal to that is that there is no math—but there are things you can do. There’s so much serendipity involved, so I’m talking about things outside of what you look like—which you can’t control, unless you spend a lot of money—your talent—which you can’t control unless you’re born with it—and your moxie—which is just something you need to have. Outside of those things, it’s just the luck of the draw, and you can increase your odds by making your own stuff.

It’s also about doing as much stuff as you can outside of really terrible projects—but you’re also going to be involved in those, because you have to take risks. It’s like a craps table, and the best players at craps, so I’m told, are the people who place a lot of bets. My dumb analogy—and this is stupid, but I recognize it is—is that I recognize myself as an octopus. If you’re an octopus and if you’re not using all eight arms to grab onto stuff, then you’re not being a very good octopus—even though that’s not how octopi work. It’s a weird metaphor, but in my brain, that’s how it works. You have to be hungry for it.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

(Photo via thesomegirl / Getty Images) -

vuk8691/Getty Images -

Tru-Tone