This article originally appeared on VICE Germany.

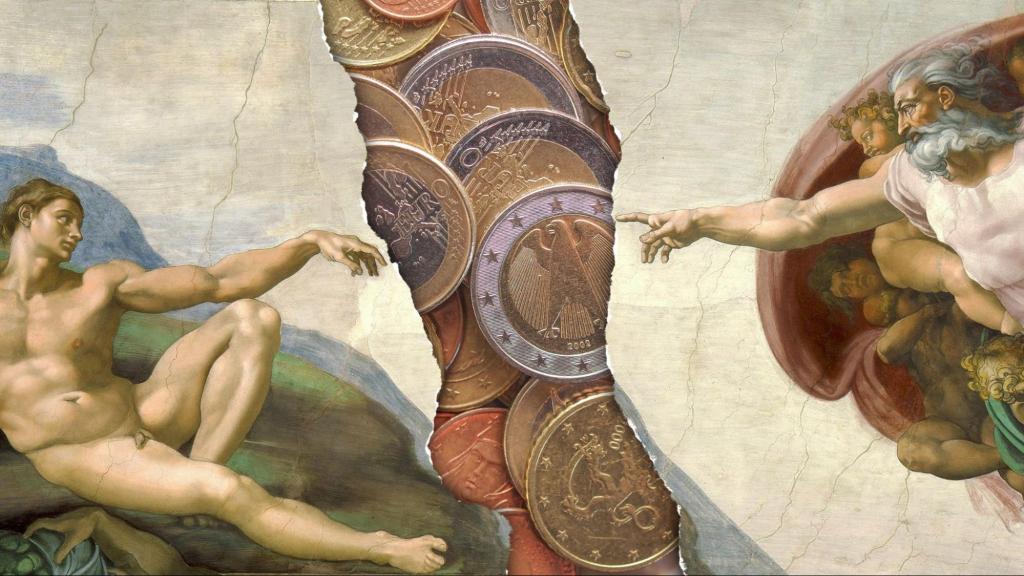

Little-known fact: Christians and Jews in Germany pay between eight and nine percent of their payroll tax to the church or synagogue every single month. This practice, known as Kirchensteuer (“church tax” in German) or Kultussteuer (“worship tax”), sees worshippers help fund the religious institutions they were baptised in and registered with as kids. Those include Catholic and Protestant churches and Jewish synagogues, while Orthodox Christians, Buddhists, Muslims and a few other groups are exempt.

Videos by VICE

Just to put this in context, that means that someone who earns the average monthly Berlin salary of just over €3,500 before taxes will end up paying more than €46 in church tax. It’s calculated based on your payroll tax, AKA the tax on your income and salaries withdrawn at the end of the month, which in Germany can vary between 14 and 45 percent. In this example, over the course of a year, you will be “donating” €550 to a service you may not even actually use.

In 2020, the Catholic and Protestant churches in Germany collected €12 billion from these slivers of tax, €800 million less than the previous year. That’s because more Germans than ever are opting to quit the church, partly in an effort to escape a tax that’s been enshrined in German law in some form since 1919. In 2019 alone, over half a million people left the church, with numbers dropping drastically for both Catholic and Protestant denominations. A 2021 Report found an additional third of German believers who pay the tax considered leaving the faith last year, too.

One of those ex-attendees is Andrea, 26, who quit the Protestant church in 2020. Her decision came during a Christmas spent with family in Gütersloh, a small city in western Germany. Her grandmother asked Andrea when she’d last visited church. The truth was, she hadn’t stepped inside one since she went on a school trip in 2014. “The fact that it had been so long didn’t sit well with her,” Andrea says. “She told me she’d pray for me. That’s when I made the decision to leave completely.”

Andrea had already been considering doing this for years, since she moved to Hamburg to study, but she could never go through with it. “It was partly laziness, partly ignorance, and partly because I didn’t want to disappoint my granny,” she says.

Carsten Frerk, a humanist and expert on church finances, explained that German Christians are theoretically only supposed to pay the tax once they’ve officially become a member of their church following their confirmation. However, in practice, anyone who’s been baptised ends up having the tax detracted from their payroll at the end of the month.

There are, of course, other reasons why more and more Germans are deciding to leave the church. In Germany as elsewhere, the Catholic Church has been rocked by many scandals. In June 2021, Cardinal Reinhard Marx, one of the most senior clergymen in the country, offered his resignation – which the Pope declined – in response to a report that found that the German Catholic Church covered up at least 3,677 cases of child abuse between 1946 and 2014. In August of that same year, the nation was shocked by the gruesome details of a decades-long case of sexual abuse of minors that happened in the 1960s and 1970s in a home ran by the Catholic Church near Munich.

High-ranking church officials often attempt to cover things up using out-of-court settlements. But when it comes to compensation, the German branch of the Catholic Church is surprisingly cheap. In the past three years the archdiocese of Cologne has spent around €2.8 million on media lawyers and communication consultants, but only a little more than half that sum on child abuse survivors.

Taxpayers’ money is being wasted by the church in other ways, too. In 2013, Bishop Franz-Peter Tebartz-van Eslt became notorious thanks to revelations about his profligate spending. Inspired by the Pope’s gilded residences, the German bishop spent over €31 million on the renovation of his house. Yes: €31 million.

While many churches impose some form of tax on their believers, the German system is somewhat stringent. For instance, Italy and Spain require people to donate a portion of their annual income – 0.8 and 0.7 percent annually – on a €3,500 salary before taxes, that’s about €24.5 to €28 per month compared to the €46 in Germany. Plus, taxpayers can choose whether to send the money to a church or to a secular organisation (like a research institute), regardless of their religious affiliation. But other countries in Europe require believers to pay a worship tax too, like Austria, Switzerland, Finland, Sweden and Denmark.

Frerk invokes France as an example of a country that takes a different approach to tithing. There, he says, there’s no church tax, but instead a day when people donate to their church. “That promotes the church system,” Frerk says. Pastors would often invite themselves to dinner with families in their congregation and join them at the supper table. “It’s a win-win situation; the family feels honoured that the pastor is joining them and says grace,” Frerk explains. In exchange, the church gets a modest financial leg-up.

Thankfully, leaving the church in Germany – in official, legal terms anyway – is quite straightforward. All you need to do is be over the age of 14 and in possession of a valid passport or ID card. It isn’t entirely without complication, though, as each German state has slightly different rules and regulations covering the self-expulsion process. In Berlin, Brandenburg, North Rhine-Westphalia and Thuringia, for example, you have to visit an actual court. Elsewhere, a visit to a registry office will suffice. Some states ask you to pay a fee, others let you leave for free. No state, however, requires you to formally declare the reasons behind your decision.

Andrea had to take a day off work to leave the church and make an appointment at the local court beforehand. “The fact that I had to show up in person was annoying,” she says. “Sure, it went quickly in the end, but I had the feeling that it was made extra difficult. After all, I can cancel a newspaper subscription by mail.”

After you’ve paid the fee, you’ll receive an exit certificate in the post. You have to make sure to keep this safe – it is the ultimate, irrevocable proof that you’ve legally left the church. If, for some reason, the tax office demands you start paying church taxes again, evidence of this document should see those charges rescinded.

The fact that the church is informed can cause headaches, though. Andrea received a letter from the pastor of her former parish, who wanted to hear the reasons for her resignation, pestering and prodding like a jealous ex. The letter also informed Andrea that she had violated her duties as a Christian.

Still, she has no regrets about renouncing her affiliations with the Church. The money that went towards it now goes into her retirement savings. “That seems more reasonable to me,” she says, “than speculating on a fulfilled life after death.”