Screenshot from Reely and Truly

Most of us will never shoot a Miley Cyrus album cover, and most of us probably won’t use our downtime from shooting Miley Cyrus to make a poetic and poignant documentary about photography. That’s because, barring unforeseen technological advancements, we will never be Tyrone Lebon.

The London-bred photographer and filmmaker’s ethereal work met initial success when, at just 18 years old, his surf documentary aired on MTV. Having made a name for himself since then by working with everyone else’s wish-list of clients including Supreme, Stussy, Nike, and Vogue, Tyrone has now turned his camera on a far more elusive subject: the photographers lurking the periphery of his world. In his latest project, Reely & Truly, Tyrone and his camera travel the globe to meet a diverse array of the most essential people taking pictures today, including some of VICE’s favourite photogs: Peter Sutherland, Petra Collins, Tim Barber, Lele Saveri and Sean Vegezzi. Later this year the project will culminate in a book, complete with photos, writings and films of over thirty contemporary photographers.

Videos by VICE

The beautifully shot result is a ponderous journey into the mind of an artist at his most reflective. While Tyrone displays a host of talent on-screen, the film is less about profiling the individuals, and instead concerns itself more with the implications of what pictures represent to those who take them. Philosophical and bewildering, the film will immediately enamour anyone who’s ever been affected by flipping through, scrolling past, or taking photos. We sat down with Lebon to chat about his film, his career, and why you probably shouldn’t shoot on IMAX.

VICE: Reely & Truly will culminate in a book, but usually you see films being based on books. What you made you decide to do the opposite?

Tyrone Lebon: I guess I was always planning on it being quite a long-term, slow, gentle project, and I travel quite a lot for my own work, so it’s something I was allowing to slowly happen in these little windows. I left university and wanted to make documentary films and it was such a struggle to earn a living or get any funding that I ended up assisting and taking pictures and went on this long tangent. So for about five years I’ve been working as a photographer, and I got really busy, which was great, but after about two years I’d run out of steam. I needed to get back to more of my projects. The book project was always going to be a series of short films about individual photographers. The final film is only 25 minutes long, but all along I knew I was gathering more material than I needed for that. The edit that exists is so fast moving, you barely have any time to rest with anyone.

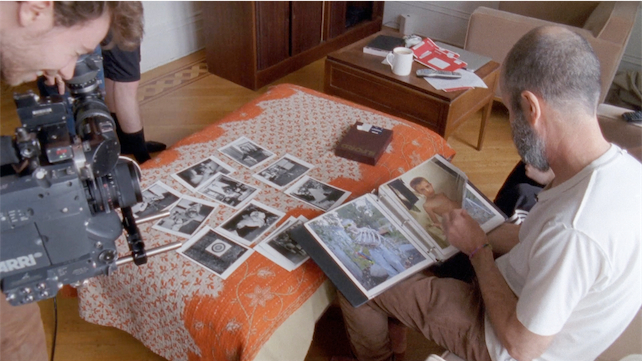

Screenshot from Reely and Truly

So is the book the director’s cut of the project?

I guess, yeah. It’s gonna have essays and photos and in the back it will be a couple DVDs with 30 odd, short little portraits.

How did you decide who to profile? Were you trying to be as diverse within contemporary photography as you could?

Yeah, and I’d be the first to say it’s lacking in a few departments. I really wanted to have a wedding photographer and a photojournalist/war photographer. But I learned very quickly how crazy and annoying photographers actually are, and how tricky it is to pin them down. I did a lot of emails over the course of nine months. The reason lots of photographers like being behind the camera is because they don’t like being in front of it. So it’s quite a big ask to get them to open up, in that way.

Did you find photographers were difficult subjects to film?

Yeah, some people, but some people loved the attention. Everyone’s different, but overall, in terms of how I chose, I had a wish list of my favourite photographers and people who always interested me. It wasn’t always people whose work I especially liked all the time, just people who had something interesting about them. You could tell they had something to say.

Tell me about shooting on film. That must require incredible patience knowing the other possibilities.

All my photography, as well, is mostly on film. I really enjoy shooting film, and to be totally honest, it’s such a part of my process that I would be quite intimidated at the thought of making a film digitally. I rely so much on the quality of film to tell the stories that I like and in the way I want them. It’s just how it has to be. It was hard working as a one-man band doing sound, and doing sound with film, because there’s no sync. So not only are you recording the sound, but you’re trying to keep notes of things people say and what you’re filming to try and later on stand a chance of linking them back together.

Do you ever do multiple takes while filming, or is what we see the only one?

No, I never ask people to do something again or re-say anything. Lots of audio in the interviews is obviously recorded separately. After a while you get really hungry for those moments where you see words coming out of their mouth. So I’ve kind of made a big effort to get those moments, but they are tricky. As every second ticks by, you’re counting how much it’s costing you. The film I actually used is this defunct, 200-foot magazine. You can’t buy them; you have to get them re-loaded, and they’re really tricky to reload. I only had a certain number of rolls going into that, so a lot’s left to fate.

That’s the moment when I think you’d say, alright, enough of using film.

It somehow always worked out, even if it got badly fogged, or I didn’t get certain things, I accepted that as the whole process and included those mistakes as part of the film. You can see it all embraced in the film. There was a lot of experimenting from animated stills through to super 8, 35mm, super 16 and IMAX. My DOP [director of photography] Evan Prosofsky kindly did all the IMAX. All the portraits in New York were shot on IMAX, which was another retarded story. It took three people to carry the camera.

Screenshot from Reely and Truly

The narration in the film often talks about truth and its relation to photography. Is this a theme that vexed you, as a documentarian whose goal it is to reveal truths?

In making a film about the nature of truth in photography, you’re putting a mirror right up to yourself. I don’t think I’ve come to any solid answer. I don’t think I ever tried to show any distinct answer. I think even the most passionate photographers are the ones who just spend their whole life questioning and are never satisfied. That’s the whole point in taking pictures and photography, is to be that person who really is never satisfied with it. It’s just a constant investigation.

What did you feel you learned about photographers from this?

They’re all bloody annoying. As far as having a shared characteristic, I’d say it’s a lot of obsessive people. But anyone who’s passionate about anything becomes like that. Lots of the people I was interested in are people who are really dedicated to what they do, so by their nature they were quite obsessive. What I loved is that everyone was so different and some people I’d never met just had the lightest touch, while some were more bitter and caught up in it all. Some people were trying to work it out and others had a clearer idea of how it fit in with their life.

Was there something about the trends or people at this time in photography that made you want to capture it?

I studied anthropology at university and I wrote my dissertation on the photographer, and at that point I actually tried to hand in a documentary as my final dissertation. But because it was quite traditional at Edinburgh University, there wasn’t a chance that I was going to be able to do that. From when I was 21, I’d had this film in the back of my mind, even if it kind of morphed a few times it had been there for over 10 years. I think it’s pretty timeless for me. I definitely feel like it’s not a boring time in photography. In the fields that I’m aware of, it feels like a transitional time, which is very exciting.

The narrative is rather non-linear and more of a philosophical stream of consciousness. Was that something you’d always had in mind from the beginning?

I think that’s just me by nature. I ponder things. It all came together in the edit. I’m not really good at planning films, I don’t really write a script and plan the same themes to ask different people about. I’ve learnt as I’ve made more films just how important it is to have a structure and a plan of some kind, even if you want to go against that in the end. It’s important to have some sort of limitations to focus you a bit. The editor and I just locked ourselves away for six weeks and worked the whole thing out in the edit suite, really worked through the footage and we probably had hundreds of hours, but we had to go through it all. Some of our edits started at an hour long and ended up as two minutes.

Screenshot from Reely and Truly

What about the film do you hope will register with audiences?

The nicest thing is when I’ve had people write to me, or friends say it inspired them or put them in a good mood to get on with their work and re-engage with not just their photography, but other things too. For it to be motivating and exciting feels good. I didn’t really have an aim as such.

It must’ve just been that drive to finish what you started.

I think it was just to satisfy something in me. I’d just been down this funny rabbit hole, working pretty hard at commissioned work, which was amazing, and I knew it was serving a purpose, but sometimes when you’re in a little bubble for that long and working in a world that’s so close to what you really love to do, you start to feel like you’re making compromises. I just needed time to breathe, to look at other people and what I was up to and think if I really wanted to continue working like that for the rest of my life. And I think it did that. I’ve come back to photography and thinking about other film projects with a new energy and feeling clearer-minded.

Where do find yourself looking at photos most often now?

Just because it’s so easy, I spend more time looking at them on a screen. When I really take my time and look at pictures they will always be in print. I’ve got a bit of an addiction to photo books.

Do you see your idea for the book, blending both digital and print material, being a new phase of the photo book?

Maybe. I’m quite stubborn about the way my photos are shown. I don’t like the way stuff goes online. Photos end up representing me through Google and it’s pictures that I’d never pick. That’s totally out of my control, and looking at others people’s pictures I know it’s the same thing. It’s a very different way of looking at a picture backlit on a screen in low resolution. But with film, I find I can be sitting on my laptop with headphones and I’m pretty close to getting the same experience out of that [as I would] at the cinema. I feel film is done a lot more justice on the internet. But photos are just so different. Especially as I shoot so much on film and hand-print my own work, when you see how your picture ends up and the colours have gone to shit, it ends up like a bastard brother of what the work could’ve been. There’s only so much you can think about that without turning into a total psycho though.

The Reely & Truly exhibition , featuring the work of photographers in the film, runs from now until March 29th at the Gladstone Hotel in Toronto.

More

From VICE

-

Beyond Power -

Seth Ferranti, all images courtesy of him -

Screenshot: Singularity 6 Corporation -

Screenshot: Square Enix