Ben Valdez needs a new car. He has been driving full-time for Uber and Lyft in Los Angeles for almost six years and his 2016 Toyota Prius C has more than 240,000 miles on the odometer.

In theory, Valdez should be a great candidate for switching to an electric vehicle. He drives a lot for work—somewhere between 400 and 700 miles a week depending on whether he’s doing more food delivery for Uber Eats or traditional ridehailing—so he would save money on fuel. Plus, even though Valdez lives in an apartment and doesn’t have anywhere to charge a car at home, he drives in Los Angeles, so Valdez has access to one of the most robust public charging networks in the country.

Videos by VICE

Valdez understands the theory, but he doesn’t think it matches reality quite yet. In a recent interview with Motherboard, he said he plans to get a Toyota Highlander hybrid instead, which gets 36 miles to the gallon according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s fuel economy ratings, about 15 miles per gallon worse than what Valdez says he has been getting on his Prius.

This is the exact opposite direction that California regulators want Uber and Lyft drivers to be going. In May, the California Air Resources Board passed a rule that mandates the ridehail giants increase the number of miles its vehicles travel powered by zero emissions on an increasing basis. By 2025, 13 percent of each company’s vehicle miles traveled must be electric. By 2028, 65 percent. And by 2030, 90 percent must be electric. (A different regulatory agency is responsible for deciding the penalties for failing to meet these benchmarks, but hasn’t decided what they will be yet.) CARB’s analysis found that in order to reach that goal, 43 percent of all ridehail vehicles would have to be electric by 2030 as long as it is the 43 percent that drive the most, like Valdez.

In other words, CARB just passed a rule that’s supposed to get drivers like Valdez to switch to electric vehicles, not get cars that are even worse for the environment. This wouldn’t merely undermine CARB’s goals, but also Uber and Lyft’s. Both companies have made even more aggressive pledges than CARB’s regulations mandate and say they will be all-electric by 2030. They plan to accomplish this mainly through lobbying efforts for more EV incentives that would apply to drivers.

Valdez is aware of all of this, and he has nothing against electric cars. But there is one big challenge with CARB’s new rules and the push for electrification for ridehail vehicles: there is no such thing as “Uber’s fleet” or “Lyft’s fleet.” Ridehail drivers pay to use and maintain their own vehicles, a central proposition of the gig economy model that allows the multi-billion dollar companies to pass the costs of vehicle purchase and maintenance onto low-wage workers. And so the decision of which car to buy is not an institutional one made by a big company with hundreds of thousands of vehicles and large purchasing power, but to individual drivers like Valdez.

“I’m paying 100 percent of the cost,” Valdez said, so he has to do what makes the most sense to him. And, despite all the claims about the future Uber and Lyft want, many of the incentives still reflect the oil-dominated energy landscape we have today.

A few years ago, Valdez looked into this when Uber and Lyft slashed the per-mile rate for drivers in Los Angeles. He was looking for a way to make more money and considered the cost savings EVs might offer. During this research, he found that if he gets a Highlander or similarly-sized six-seater SUV, it will qualify as an “XL” vehicle for which Uber and Lyft will pay him roughly double his per-mileage earnings on qualifying ridehail rides, from about 64 cents a mile to $1.20. Over the hundreds of thousands of miles he will put on the Highlander, Valdez figures the extra money he can earn would cover the roughly $40,000 suggested retail price of the Highlander as well as the extra fuel costs compared to the Prius.

But, there are currently no electric vehicles that seat more than three passengers standard and could therefore qualify as an XL. The biggest EV, the Tesla Model X, comes in an optional seven-seat configuration, but it starts at $93,500, more than double the suggested retail price of the Highlander hybrid. More may come on the market in the coming years—an electric Cadillac Escalade is rumored to be in the works—but they are unlikely to be significantly cheaper given the battery size required to power them.

Uber and Lyft do have incentive programs for “green” rides, but it pays out a fraction of XL rides. Hybrids and EVs can accept “green” rides, which riders opt into in select markets by paying an extra $1 per ride. The companies then split that dollar 50/50 with the drivers. Uber and Lyft say its own half goes into a fund that, ironically, is used to encourage drivers to switch to electric vehicles. Uber says it also gives electric vehicle drivers an extra $1 per trip, meaning drivers can receive up to $1.50 per trip on top of the regular fare.

But Valdez already gets that 50 cent green fee on the rides that qualify because he drives a hybrid, which in Uber and Lyft’s accounting are “green” vehicles. So, he would continue to do so if he got a Highlander hybrid.

Incidentally, the green fee may have unintended consequences, Carnegie Mellon professor and director of the Vehicle Electrification Group Jeremy Michalek told Motherboard, such as actually increasing emissions by having the limited number of qualifying vehicles travel further to match with riders.

Motherboard requested interviews with both Uber and Lyft regarding their vehicle electrification policies. Uber declined an interview and responded to written questions only. A Lyft spokesman said he had to cancel a scheduled interview with Lyft’s head of sustainability due to a scheduling conflict, but also replied to written questions. In those responses, both companies said XL vehicles actually lower emissions because they often have more passengers, thus emitting less than if the passengers had to use multiple cars.

But those analyses only consider rides where the XL option is selected by the rider and therefore doesn’t tell the full story. When no XL rides are available, Uber and Lyft will match XL vehicles with regular Uber and Lyft ride requests. (I do not use ridehail often, but when I do, I get assigned a large SUV more than half of the time despite never requesting one. I also had no idea before I reported this article that the “Green” option existed, but I did know about “XL” because it is a prominently displayed option on both apps.) Neither company provides an analysis of the emissions impact of XL vehicles for all rides they provide, tipping the scales to make it look like XL vehicles are better for the environment than they are.

But the problem for Valdez switching to an electric vehicle extends beyond the XL ride incentives. It has to do with the very nature of the gig economy business model.

It is true ridehail vehicles are great candidates for early electrification based on the kinds of trips they make. Alan Jenn, a researcher at the University of California, Davis who has studied electrification of ridehail fleets, told Motherboard that over the millions of trips of both types of cars he’s evaluated, he has found “no statistically significant difference” between gas and electric cars on the number of trips completed or the miles they travel, even though the “vast majority” of charging events are occurring at public charging stations, not private ones.

But while ridehail vehicles are great candidates for electrification, ridehail drivers tend to differ from the profile of people buying electric vehicles right now. While EV buyers tend to be higher income earners who can afford the pricier vehicles—and take advantage of the tax credits—ridehail drivers tend to be lower income, which makes buying an expensive EV which tend to be luxury models “untenable” for many of them, as Jenn put it.

“It’s really hard to think about buying a luxury vehicle when you’re not getting fair pricing for your rides,” siad Nicole Moore, a ridehail driver since 2017 and leader of Rideshare Drivers United. “People are just not getting, after expenses, even minimum wage.”

The big question, Jenn said, is who will be responsible for bridging that economic gap. Will state or federal governments step in with bigger incentives that come out of the purchase price rather than tax credits? California has already started to do this to a limited extent. Will Uber and Lyft offer some kind of credit? Lyft has hinted it may be open to “negotiate with auto manufacturers for group discounts for drivers using the Lyft platform,” although it’s not clear whether this would involve any money coming out of Lyft’s pocket. Or will the industry rely on falling EV prices and hope that, because full-time drivers go through vehicles every 4 to 6 years, there is still time to buy one more gas car before the regulations kick in, impact on the planet be damned?

In the short term, Lyft is most excited about getting more drivers into electric vehicles using the Express Drive program, which partners with rental car agencies, and allows drivers who cannot afford EVs to use one right now by renting one. Lyft says drivers save $50 to $70 a week on fuel. But the scale of this program is simply too small to hit meaningful goals; just a few hundred EVs are available to be rented out across the three pilot cities of Seattle, Atlanta, and Denver, and it’s not clear how much the program can be scaled up.

EV usage is similarly limited in other major ridehail cities. There are two major ridehail markets that have publicly available data on ridehail vehicle types. Chicago does not specifically say if a ridehail vehicle is gas, hybrid, or electric in its open data portal, but it does list the make and model. Of the 49,563 vehicles registered to give rides in April, the most recent month for which data is available, just 87 were Teslas and 11 were Chevy Bolts, the two most popular electric vehicle brands. New York City doesn’t specify the make and model of the city’s for-hire vehicle fleet, but it does have a field that denotes hybrid or electric vehicles. According to that count, the city currently had 1,480 hybrids, 460 electric vehicles, and 89,009 regular gas cars. (New York City’s Taxi and Limousine Commission has had a cap on new for-hire vehicle licenses since 2018, but it allowed exceptions for new EVs until this week when it ended that exemption.)

These statistics exemplify what seems to be a gap between what the experts say and what drivers believe. The experts are convinced that buying an EV will save ridehail drivers money not 10 years in the future, but today. For example, a Volkswagen ID.4 small SUV, which just came on the market this year, starts at $40,000—roughly the same as a Highlander Hybrid—and according to Jenn’s research, will be three to four times cheaper to power with electricity than buying gas. With a range of about 250 miles, a driver like Valdez would have to charge it two or three times a week. And both ridehail companies have partnerships with major fast charger companies that reduce charging costs.

So are drivers like Valdez simply being irrational, slowing down the electric revolution and working against their own self-interest? Even though he is one of those experts, Michalek doesn’t see it that way.

Although there “may be truths about EVs that are well known by experts, policymakers or companies but not yet well understood by average consumers or drivers,” Michalek said, “there may be things most experts believe that turn out to be false because experts make different assumptions than drivers.” He added that we shouldn’t confuse “the wait-and-see approach that a lot of consumers take” with irrationality.

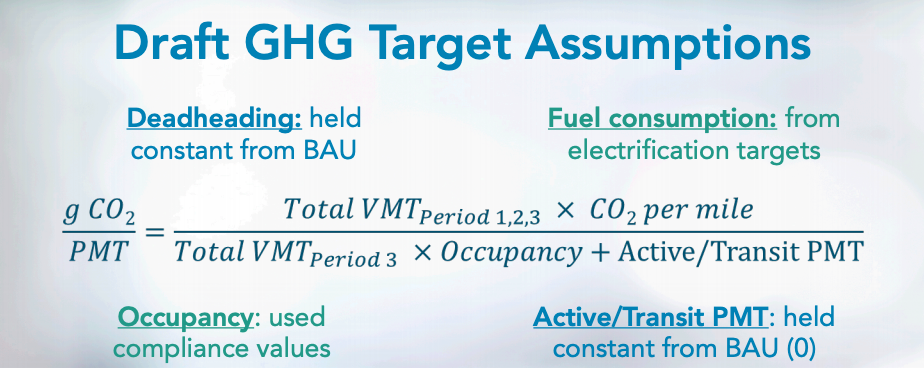

To his point, much of the back-and-forth over the CARB regulations between policymakers, professors like Michalek, and interested parties like Uber and Lyft had to do with precisely how to calculate those assumptions, which involve formulas like this:

which may or may not reflect reality.

Valdez also carefully considers what to do based on his lived experience. A key part of his calculation is embracing uncertainty rather than trying to quantify it. Uber and Lyft can, and have, reduced his take-home pay with the flip of an algorithmic switch. Plans that sound nice on paper suddenly become financially untenable. He’s deeply skeptical of rental programs like Express Drive that operate through the ridehail companies because he recalls the ones of the past that charged exorbitant rates and trapped drivers in debt. Both he and Moore said they would be extremely hesitant to take an offer from Uber or Lyft to subsidize the cost of a new EV, worrying about onerous terms and conditions or even reneging on the deal in the same way that product features, bonuses, and rates of pay come and go by the week. Valdez knows the entire business model of ridehailing is to experiment on drivers and pass all the costs and risk off to them. So whenever there is some aspect of his job he can control, he goes for the lowest-risk approach.

Along those lines, there is the issue of range. Although Uber and Lyft have previously had this feature, drivers can no longer see the destination of a ride until they accept it. So EV drivers may be forced to cancel potentially lucrative longer trips if they’re running short of range, which would also hurt their rating, impacting their ability to get similar trips in the future. But with a gas car, drivers can simply make a quick stop for gas along the way.

“You never know if you’re going to get into a car accident, you never know if you’re going to be deactivated,” Valdez said. “You don’t know if the rates are going to drop. There’s just a lot of uncertainty.” In a profession where very little can be counted on, there is one thing Valdez knows: there will be a gas station nearby when he needs it.