Pakistan has an abortion problem. For decades, women have been resorting to methods that put their lives in danger. This, even though abortion is permitted in the first four months of pregnancy.

The most recent national study of abortion was conducted in 2012, and the numbers painted a bleak picture. For every 1,000 women aged 15 to 44, there were 50 abortions. Most of the women undergoing these abortions are typically older, married mothers from lower-income families who seek procedures from untrained, back-alley services — usually more than once. Some also do it themselves through dangerous methods like swallowing anti-malaria pills and sticking wooden sticks or other sharp instruments into their bodies.

Videos by VICE

An estimated 623,000 Pakistani women were treated for complications resulting from induced abortions performed by unqualified providers, in 2012. Some of the complications they suffered included incomplete abortions, hemorrhage or excessive bleeding, trauma to the reproductive tract, or a combination of these.

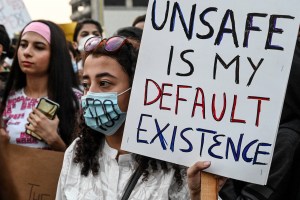

Still, more women take risks with unqualified attendants because of a lack of awareness, and the stigma that still surrounds abortion — it could be that they’re afraid of others finding out about their pregnancy or abortion, that they’re not aware of the legal options available to them, or that they’re turned away and judged by health practitioners. For many Pakistanis, abortion is a sin.

“I’ve been working with the community, stakeholders, other NGOs — the same things would come up. They would say, ‘But this is murder. This is illegal in Pakistan,’” Saba Ismail, peace activist and co-founder of Pakistani abortion hotline Aware Girls, told VICE World News.

The Pakistani government and various non-governmental organizations have been working on improving the state of reproductive health in the country to little avail. Pakistan’s abortion law, which was inherited from British common law, originally stated that abortion was a crime unless performed to save a woman’s life. This was amended in 1990, allowing abortion if the procedure constituted “necessary treatment” within the first 120 days of a woman’s pregnancy, inline with Islamic teachings.

“The law as it stands does not attempt to regulate a woman’s body. It does not presume to know what is needed to maintain a woman’s health, because that’s the job of a doctor or a service provider. And it allows that decision to rest with the service provider, who is a trained professional and can understand health and biological needs or even social needs for women,” Dr. Xaher Gul, a medical doctor and public health policy expert, told VICE World News.

But some believe that the vagueness of Pakistan’s abortion law is the reason behind the high number of unsafe abortions. Because the parameters of what counts as “necessary treatment” are undefined, many medical practitioners only provide abortions in the case of serious medical conditions, like if a woman comes in after self-inducing an abortion. Otherwise, many refuse to conduct the procedure, holding on to conservative views.

Majority of healthcare providers still have an unfavorable view of abortion. Ismail said that she has met gynecologists who proudly state that they’ve “never even given a pail to a woman for abortion.” Many doctors aren’t even aware that abortion, in the circumstances afforded by the law, is legal.

“The law of the country and particularly the abortion law is not part of the teaching curriculum in medical colleges,” Dr. Mariam Iqbal, a gynecologist and reproductive health advocate, told VICE World News. “And you know, we go by what we hear. When I was in medical school, for example, I always thought abortion is something a doctor cannot do, and you would lose your license if you did it. When I came into clinical practice after working with a lot of reproductive health organizations, that’s when I realized and read up on it — that, in fact, the law gives a very open clause for doctors to make a decision.”

According to the experts VICE World News spoke with, women are not incarcerated for undergoing an abortion and there are no governing bodies that police medical practitioners who perform the procedure. Still, any talk of sex or relating to sex is taboo in Pakistani society.

“Women are never educated about these things. Talking about sex before marriage is taboo. There’s no guidance for women before getting married. There’s nothing like sex education in the school system. When I was in college, there used to be only two pages about the reproductive system,” Ismail said.

Gul said that censorship is also an issue. The word “condom” is not allowed on TV and radio, so ads for the contraceptive are banned too. “[This] reduces the effectiveness of reaching people with the right message,” Gul said.

The conservative view of sex, then, extends to family planning.

“The fact that Pakistan is the fifth most populous country in the world says a lot about the use of contraception in the country,” Iqbal said.

According to Pakistan’s Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) for 2017 to 2018, more than 98 percent of currently married men and women had heard of contraceptive methods, both traditional ones like withdrawal, and modern methods like IUDs. However, only 34 percent of currently married women were using some method of contraception at the time, and 17 percent had an unmet need for family planning. More women had tried one form of contraception at least once, but chose not to keep using these methods for various reasons.

Five years before the survey, 30 percent of those who have used contraception discontinued within 12 months because the women experienced either side effects, health concerns, or method failure. According to the study, the method failures imply that women who do use contraceptive methods may not necessarily know how to use them correctly.

The survey also showed that only 19 percent of women made an informed choice — meaning they knew about a contraceptive method’s potential side effects, how to deal with those side effects, and alternate family planning methods available, when they started that method. This is an important statistic because there’s a correlation between knowledge and contraceptive use. The more women know about a certain contraceptive, the more likely they are to use it.

Many women from lower-income groups also usually have less financial autonomy and mobility, and can’t use contraceptives without their husband’s approval. And in Pakistan, many associate a woman’s worth with fertility.

“We are a very conservative, patriarchal society. And the idea that women, if they are not actively reproducing, will become sexual beings,” Gul said. “Having said that, misogyny is not particularly stemming only from men. In Pakistan, it is the women who are the tools of patriarchy themselves. For example, the mother-in-law features heavily in making sure that the daughter-in-law is sufficiently reproductive. Women themselves feel that their utility within the household is if they continue to reproduce.”

For these reasons, the country continues to have one of the lowest contraceptive prevalence rates in the region. This contributes to the heightened number of unplanned pregnancies and, in turn, abortions in the country. Many women even see abortion as a form of birth control.

“In our culture, men do not use contraceptives, although condoms are available at every corner store in the country and are extremely cheap. When it comes to using condoms, men consider it against their honor,” Ismail said. “The primary responsibility of the contraceptive then falls on women. If women have to be the ones to use contraceptive pills, and they don’t and it results in unwanted pregnancy, then the burden of abortion also falls [on them].”

While the policies and intentions are there, the road to better reproductive healthcare and family planning is a long one. According to Gul, one of the biggest challenges women’s health advocacy organizations face is implementation. Resource allocation to health overall is around 1 percent or less of the country’s GDP, and much of the budgetary allocations are spent on salaries.

For Iqbal, one way to reduce instances of unsafe abortions is by training midwives.

“Midwives play a very important role in the healthcare system of Pakistan because they are like the front line army. A lot of women do not come to the hospitals for any kind of treatment,” she said.

According to Iqbal, about 70 percent of deliveries happen outside government sector hospitals, with many turning to midwives and traditional birth attendants.

“They have a very important role, and if they’re trained properly and are aware of the contraceptive methods being used, they can counsel these women and probably have a greater role in increasing the contraception rate, since they’re in the community. They’re meeting more women than doctors are,” she said.

And unless women have access to safe, unbiased treatment, unsafe abortions will maintain their prevalence.

“Death and disability from unsafe abortions are totally preventable. We need to work together to promote these responsible health policies and practices. At the end of the day, it’s our responsibility as healthcare providers to be safe and to provide treatments for those who need [them]. If I don’t believe in the concept of doing abortions, for example, I at least have the responsibility to refer them to a safe place, because they would do it anyway,” Iqbal said.

For medical practitioners like Iqbal and Gul, it’s not just the law that needs to change, it’s society’s views on abortion too.

More

From VICE

-

Savannah Sly, dominatrix and co-founder of sex-worker vote mobilization group, EPA United. -

-

-

Cole and Calvin, cousins, 2017. All photos courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.