Every month since June 2009, Tad Steckler has received a disability benefits check from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Steckler retired from the Army at age 40 as a master sergeant with a Soldier’s Medal for heroism, and he’d built a new life on the foundation of his checks. The money covered rent on a three-bedroom home in Nebraska that he shared with his wife and her two daughters and the lease on the family’s Nissan Leaf electric car. It was all part of the agreement he’d made with the government when he enlisted out of high school: In exchange for his service, he’d be taken care of.

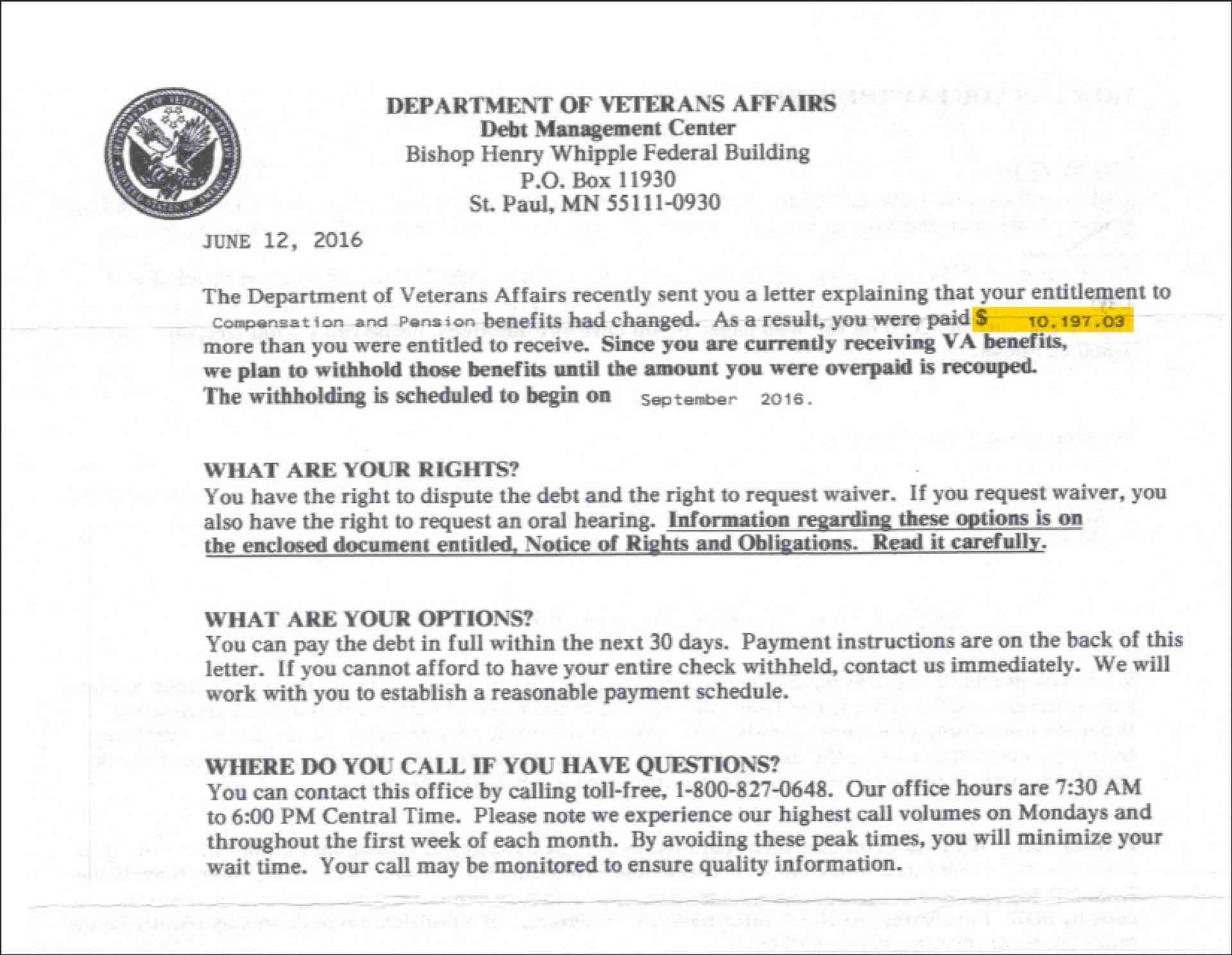

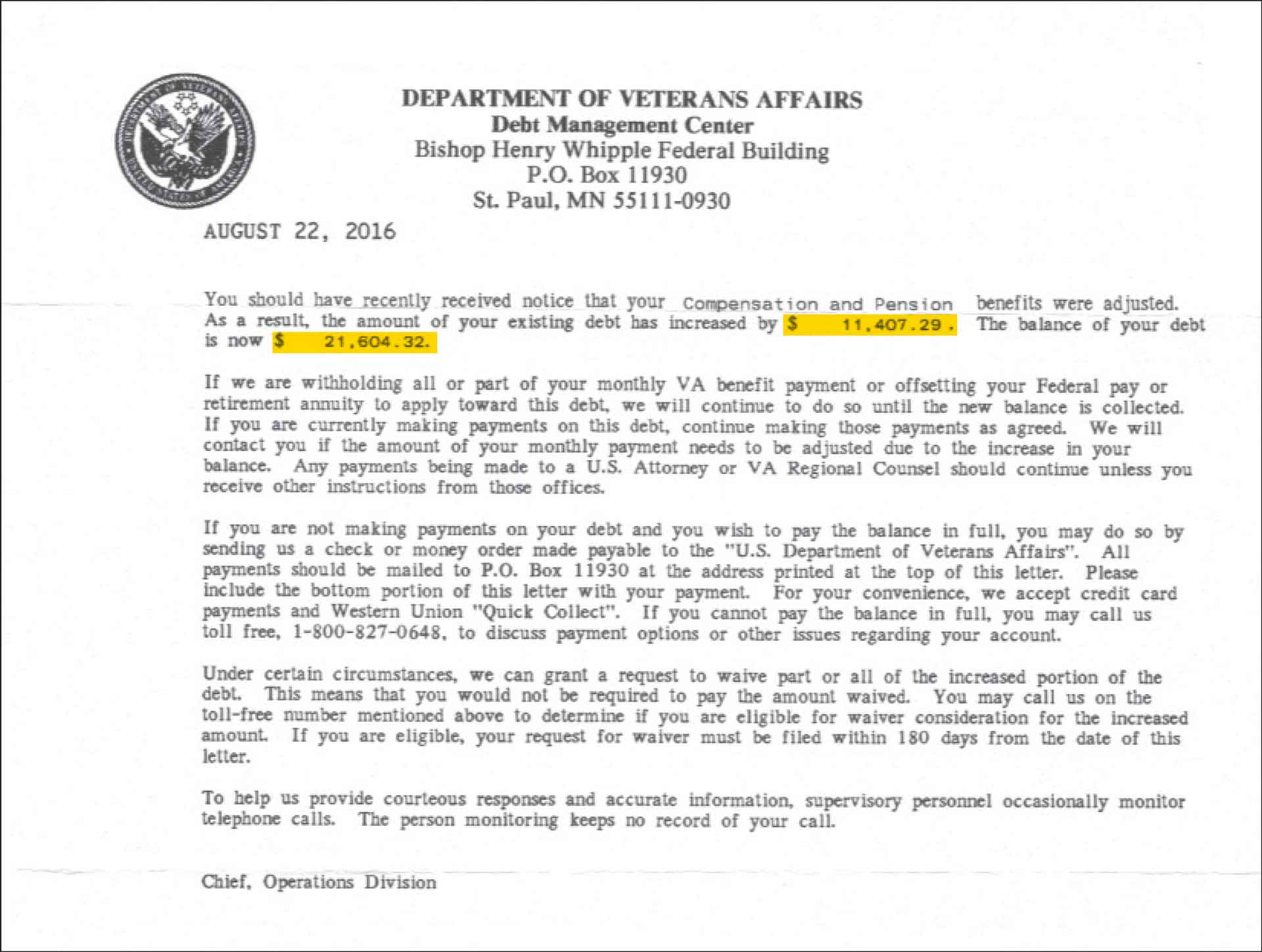

Last June, Steckler’s wife, Robyn Loveland, opened what she thought was just another envelope from the VA. Except this one wasn’t a check — it was a bill for more than $10,000. A letter stated that Steckler had received thousands of dollars in disability compensation in error, and the VA was going to withhold future payment until the debt was paid.

Videos by VICE

A VICE News investigation has revealed that the VA sent nearly 187,000 of these overpayment notices last year. That represents just under 2 percent of those receiving benefits. Other cases we’ve identified show overpayment claims similar in size to Steckler’s, with the potential to send veterans into crippling debt. A former Army combat medic from Idaho who served two tours in Iraq was told he owed the VA $9,831.93. A former Army sniper from Colorado who was shot in the head in the line of duty in Iraq got an overpayment notice for $11,119.41. These veterans were told their benefits would be withheld until they repaid the unexpected bills.

Fearing her husband’s reaction to the news and the effect it might have on his mental health, Loveland decided to keep the information to herself until she could take him for a walk-in meeting with the local veteran service office. At the meeting, Steckler twice had to leave the room because he was shaking so badly. The veterans service officer couldn’t provide them with any information about where the debt came from, but she agreed to help them find answers.

The VA said it could not provide any estimates of how much it has overpaid veterans, nor could it provide figures on the average amount of debt veterans who receive overpayment notices may owe. NPR reported the agency overpaid 2,200 incarcerated vets more than $24 million in 2015, but this is likely only a small fraction of the money the VA is trying to collect. The VA told VICE News there is no limit on how much it can ask a vet to repay, and no limit on how far back the agency is willing to go to collect overpayment debts.

Some veterans, including Steckler, are disputing the VA’s overpayment claims. They say the agency has failed to provide a clear accounting of the debts and that the labyrinthine appeals process amounts to a “one-sided conversation” resulting in few answers. One veteran said he received a notice of the hearing date for his appeal more than a month after the meeting had already been held. Without more information, veterans can’t know if they’re really at fault in these cases, or if the overpayment resulted from an error on the VA’s part.

The VA declined to comment on any of the concerns veterans have raised about the debt collection process. A spokesman provided a statement saying the Debt Management Center “hires and trains its contact center counselors to ensure that debts are collected with the special situations veterans face in mind. In fact, 39 percent of DMC employees are veterans. DMC employees provide caring and compassionate service to veterans — even working with them to design repayment plans to reduce financial hardship, while also ensuring that taxpayer interests and dollars are also protected.”

But Steckler’s experience and conversations with other veterans, family members, advocates, and lawmakers suggest the agency is inclined to demand payment first and answer questions much later, if at all.

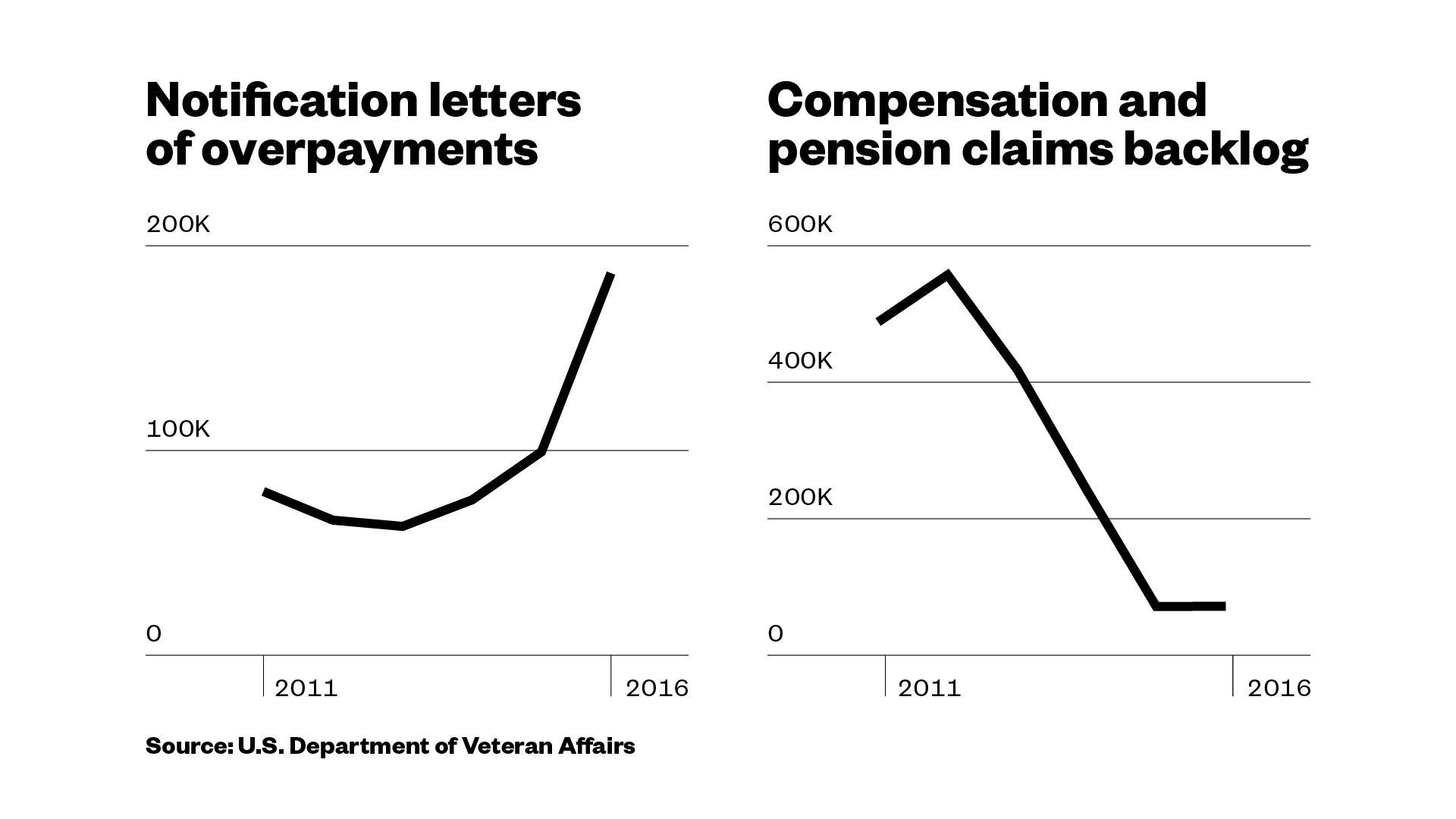

Overpayment letters from the VA’s Debt Management Center have been on the rise every year since 2013, nearly tripling in that timeframe, a spokeswoman said. They appear, in part, to be an unfortunate consequence of an agency working to respond more efficiently to its constituents after falling under heavy criticism for a seemingly endless backlog of claims.

With an influx of soldiers returning from foreign wars over the past decade, the VA has been log-jammed with disability and pension claims, hitting a peak in September 2013, when a disability compensation claim took an average of 348 days to process. The backlog received bipartisan criticism from members of Congress, and the chairman of the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee called for the VA’s top benefits official to resign.

The Obama administration made eliminating the backlog a priority, and the agency transformed its claims process, hiring and training thousands of additional employees. The backlog of disability and pension claims has been reduced to 100,000 cases and a veteran’s wait period for the VA to process a disability compensation claim is now about 116 days. But at the same time, the appeals-claims backlog has grown — an indication that the agency’s claims process is still struggling to keep up with veterans’ demands.

The effort to reduce the backlog isn’t the only reason behind the increase in overpayment notices, but it has been a significant factor, the agency said. When the VA processes claims, it sorts through data on veterans from government agencies and other sources. In some cases, this information can show that a veteran has been overpaid, usually because of a failure to account for a change in eligibility for herself or her dependents. Maybe she got a new job, or was incarcerated. She may have dropped out of school or gotten divorced. After the VA began automating its process of drill pay adjustments for National Guard and Reserve members last year, for example, it discovered some veterans had improperly been paid twice and sent 70,000 overpayment notices in September alone.

The VA provided about $80 billion in compensation and pension benefits to more than 5.1 million veterans and their spouses and dependents last year, a 23 percent increase since 2013. Single veterans with disabilities can receive up to about $2,900 per month in disability payments from the VA. The amount depends on a veteran’s disability rating — essentially a measure of how much the government thinks it owes her for her injuries. Veterans who are married, or who have kids or dependent parents, can get more, about $160 for a spouse and $100 for each child. Steckler has a 100 percent disability rating, meaning the VA considered his injuries so severe that he wouldn’t be able to work. Because he also covered his wife and two other dependents, he got $3,268.12 a month.

Over 22 years and three wars, Steckler earned that money. He had specialized in finding bombs. In Iraq, he and his team would clear the way forward for ground troops of upcoming hazards, and the IEDs would go off only a few feet away from him. The constant blasts took a toll on his body, riddling his flesh with shrapnel and damaging his brain with concussions. Steckler would jump out of helicopters, sometimes colliding and entangling with other soldiers during the fall, and he developed traumatic brain and back injuries. There was a mental toll as well: His best friend died in Afghanistan, prompting a yearslong struggle with PTSD.

Losing his monthly VA check would be a heavy blow to Steckler’s family of four, who otherwise depended on his Army retirement and Social Security disability benefits, which amounted to about $3,500 a month. “You get all of these promises that, ‘Hey, you do 20 years and you’ll get this,’” Steckler said. “And when it comes down to the end, it’s like, damn. You really can’t support your family when they are taking your whole check away.”

In a second letter to Steckler, the VA gave a broad accounting of the debt and told him the overpayment had resulted from a change in his marital status. Steckler had gone through a divorce in 2010. Before that, his wife and her two kids qualified as his dependents, and he got additional funds in his disability check to cover them. He informed the U.S. Department of Defense of the divorce when it was finalized and the department took his ex-wife and her children off TRICARE, a healthcare program for service members and their families, that spring. But Steckler didn’t know that he was also supposed to tell the VA about his divorce. He thought he had already done his due diligence. Plus, he had only recently retired from the Army and wasn’t yet fully integrated into the VA’s system.

That same year, Steckler reconnected with Loveland, his high school girlfriend, on Facebook, after more than 20 years. They began chatting regularly while he was in Afghanistan working as a contractor and she was living in Omaha. At the time, Loveland, a former lawyer, was writing a book and one of the characters was in the military. She used Steckler as a source of information for her research.

Steckler continued his contracting work, taking jobs around Africa, and they began dating long-distance, seeing each other when they could. He stopped his work as a contractor in 2014 because his injuries made work too challenging. In February 2016, he and Loveland were married in a small ceremony at sunset, down by the river near their home.

After the wedding, Steckler filed a new dependency claim with the VA to add Loveland and two of her children to his monthly disability compensation allotment. Now the couple wonders whether the new claim caused the agency to look into Steckler’s file and uncover the alleged overpayments.

After the initial meeting at their local office, Steckler and Loveland sent letter after letter to the VA and met in person with at least six different agency reps and veteran service officers to try to get a full accounting of the debt and how to remedy it. Some of these people were helpful, but they kept running into dead ends. Loveland even reached out to members of Congress for help.

As the summer wore on, Loveland observed Steckler’s mental state decline. He would make disturbing comments, telling her, “You would be better off if I weren’t here.” She worried about leaving him unsupervised.

“In a few days I will have to start driving the girls to and from school again, and I dread it. I know we will worry that he is home alone during those times. We cannot take him with us because with the added stress of this huge debt, his PTS symptoms have increased and he is back to being unable to handle traffic, noise, and becomes disoriented,” Loveland wrote in a letter to the VA in August.

Earlier that month, they had gone to the VA’s regional benefits office in Lincoln to dispute the debt. At the meeting, one of the three VA representatives there told them the debt had been miscalculated; Steckler actually owed the agency $21,604.32, more than double the figure he’d been quoted in June.

Steckler recalls looking them in the eye and saying, “Fuck it. How are you going to get the money if I’m dead?” Loveland said she started crying and ran to the bathroom.

They wanted to know if this was the end of it. Could the family be surprised again with an even higher debt? Nobody at the meeting could say whether the bill wouldn’t rise again. On their way out the door, one of the VA representatives told Steckler to take care of himself.

Worried their home would be foreclosed on, Loveland filed a request for waiver of the debt that month. She was told the VA wouldn’t take action on the debt until a decision on the appeal was made. But in September, the agency withheld Steckler’s entire disability check.

In these cases, the burden of proof is on the veteran to show she wasn’t overpaid. And when the VA decides to collect, a veteran who depends on her monthly disability check can see that check suddenly disappear. The VA may withhold benefits, as it did in Steckler’s case, even when the veteran disputes the debt.

Daniel C. Willman, a lawyer representing National Guard soldiers in California who were asked to repay their enlistment bonuses in a separate case, said veterans don’t have the same rights as private citizens in debt-collection scenarios. “If Blue Cross Blue Shield gave you too much of a benefit, they would have to sue you first; they couldn’t go straight into collections,” Willman explained. “But because it’s the federal government, it can go straight into collections.”

Some veterans argue it’s hard to prove they were paid what they deserved when dealing with the bureaucratic processes at the VA and their inability to get clear information from the agency. “VA is so fragmented that it is almost impossible to correct an error in the underlying facts before VA turns the case over for collection,” said Douglas Rosinski, a lawyer who represents veterans. “If the underlying facts are incorrect, which they are in many instances, it is nearly impossible to jump through all the legal hoops to appeal the determination before VA executes its recovery action.”

Steckler began noticing problems with his dependency status a year before he received the overpayment notice. His ex-wife’s children were still listed as his child dependents in 2015, long after the divorce, instead of his two biological children from his first marriage. (Loveland is his third wife and they do not have kids together.) When he found out, he asked to have his ex-wife’s children removed and his own children added, but the VA didn’t resolve the problem.

In a letter the agency sent him in July, the VA said it had calculated the debt by retroactively removing his ex-wife’s children as dependents dating to when he started receiving disability compensation in 2009 — meaning he’d been overpaid by about $130 per month. But Steckler said this accounting doesn’t make sense; the kids were still his dependents until May 2010, when his divorce was finalized. And if his ex-wife’s kids weren’t covered, his own children should have been added and his benefits should have effectively stayed the same.

It’s possible the entire $21,000 debt is the result of a clerical error; someone at the VA at some point could have put Steckler’s ex-wife’s children’s Social Security numbers into the system instead of his own kids’. But the couple has no way of knowing, and they can’t get a clear answer from the VA. “It’s a full-time job,” Steckler said of trying to navigate the VA’s bureaucracy. “You are talking three, four entities that you are supposed to be dealing with.”

Loveland checked her husband’s dependency status online again that month. She said the VA showed Steckler as having eight dependents — including two wives — despite their efforts to alert the VA to these errors. They have requested a month-by-month and child-by-child accounting of his payments more than four times since June but haven’t received one.

“If we owe, then we owe. We get it. But can you show me what I owe and how? I don’t know any businesses that would get away with something like this,” Steckler said.

Veteran advocacy organizations are providing support to some veterans seeking answers about the VA’s overpayment claims. Veteran Warriors said it is working with a veteran’s widow in California who owes $390,000 and another veteran in Virginia who owes $40,000 to gather evidence to dispute these debts. The Wounded Warrior Project said it is working with a veteran who owes more than $8,000 to negotiate a repayment plan.

Republican Rep. Phil Roe of Tennessee, the new chairman of the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, said that a focus of his chairmanship will be working with the VA to streamline its appeals process. “The simplest way to address this issue is for VA to get these benefit payments right in the first place,” he said. “It is unacceptable to me that VA would make veterans pay for [its] errors.”

How the VA will handle its goal of eliminating the claims backlog — and dealing with the uptick in appeals — moving forward is unclear. A Government Accountability Office report last week warned that without a “hiring surge,” the appeals backlog could grow to 1 million cases within a decade.

The VA denied Steckler’s waiver request in September, saying he was responsible for the debt because he failed to update his dependency status after his divorce. Loveland filed a request for reconsideration and a notice of dispute of the debt in October. They received no acknowledgement of these filings from the agency, but online it still says Steckler’s appeal is “pending.”

Unable to get clear answers, and unable to wipe away the debt, Steckler settled with the VA in September on a five-year plan for about $360 per month. The deduction comes out of his disability compensation check.

“They basically blackmail you with the option of losing your house and filing bankruptcy or [to] go on a payment plan for some enigmatic, elusive, ever-changing debt,” Loveland said.

A spokesperson for the VA said the agency “wants to ensure that all veterans, family members, and dependents receive the benefits to which they are entitled under the law. We regret any frustrations the Steckler family may have had during this process. We are glad that we were able to work through their various issues and come to a mutually beneficial resolution.”

But Steckler doesn’t consider paying off a debt he doesn’t understand a beneficial outcome — even at a lower monthly rate. It wasn’t what he signed up for. “You go to war and you defend all these rights for people, but then when it comes down to it, you don’t have any. I can’t tell you how much it aggravates me,” he said.

A few months before he received the first letter, Steckler and Loveland had finally purchased the home they’d been living in for five years. But with the debt hanging over their heads, they decided to downsize. In December, they sold that home and moved into a less expensive one in town. They took the funds from the sale and put them into savings so that they could be protected against any future blows to their finances. Loveland is returning to work as a lawyer, rather than finishing writing her book.

Steckler’s mental health has stabilized, and he credits his wife for her persistence in helping him to navigate the VA bureaucracy and providing the support many veterans don’t get. “If it wouldn’t have been for Robyn, because you know at least I had some support, I would probably be homeless, under a bridge, or dead,” he said. “Honestly, that’s the mood I was in. I see easily how these guys end up on the street.”

The payment plan with the VA has lessened the monthly burden of paying off the debt, and the couple’s decision to move means they no longer worry about foreclosure. But Steckler and Loveland still haven’t gotten confirmation from the VA that the debt won’t rise again. They worry another letter will appear in their mailbox.

Have you or a loved one received an overpayment notice from the Department of Veterans Affairs? Get in touch with VICE News to share your story: sara.jerving@vice.com.