By the end of this pride month, my progressive Catholic parish’s LGBTQ ministry will have, among other efforts, held “faith-sharing” events to bolster reflection on biblical readings, served dinner to community members living with HIV, and held mass outside Stonewall Inn, followed by a light reception at a gay bar. As the popular hymn says, “They will know we are Christians by our (same-sex) love.” Oh, my bad—that’s from the dance remix.

Thankfully, New York City affords my church gays and me the opportunity to live and pray as freely as we wish. And while we’re blessed to have a way of expressing our sexuality and spirituality, you’ll find no shortage of queer Catholics nationwide who fear persecution from their clergymen and congregations.

Videos by VICE

It’s still rare to find anyone in the church hierarchy today—especially a Catholic priest—who will speak frankly and favorably about the queer Catholic experience. Jesuit priest and New York Times best-selling author Father James Martin is that rare exception, having spent the past 20 years as an advocate and counselor for LGBTQ Catholics, making it his mission to affirm their right to belong in the church.

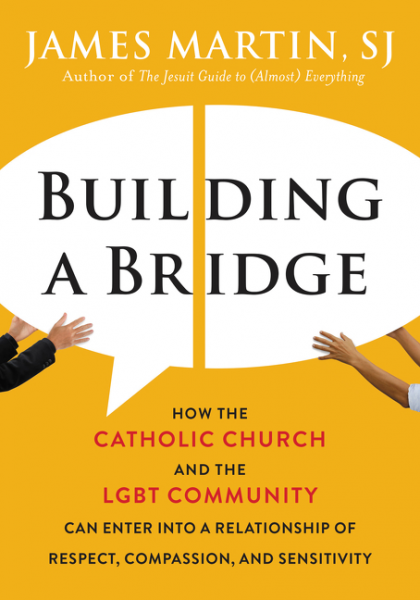

Father Martin is something of a superstar among progressive Catholics. His outspokenness on issues of social justice (you should follow him on Twitter) is refreshing, and he’s not afraid of a challenge, as evinced by his new book, released this week by Harper Collins: Building a Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LGBT Community Can Enter into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity.

In it, he challenges church leaders and queer parishioners alike to find common ground, in the hopes that the church can move forward from its homophobic past. Father Martin (who Pope Francis recently appointed as a consultant to the Vatican’s Secretariat for Communications) and I exchanged emails this week to discuss how he envisions building his bridge, and the inevitable roadblocks he faces in tearing down centuries of anti-queer church orthodoxy.

VICE: The title of the book spells it out: building a bridge. That would imply linking two sides together—in this case the Catholic Church and the LGBTQ community. But in your experience, which side of the bridge is most reluctant to connect?

Father James Martin, SJ: Even talking about “sides” can be exclusive, as if one “side” is in the church and one “side” is not. It’s important to say that LGBTQ Catholics are already in the church, by virtue of their baptism. So maybe we can talk about two “groups” in the church instead. First, there’s the institutional church—that is, the pope, bishops, clergy, and others who work in the church in official capacities—and that includes laypeople in parishes, schools, and the like. Second, there’s the LGBTQ Catholic community. In my experience, it is the institutional church that is more reluctant to reach out. Why? Homophobia, first of all. A lack of familiarity with LGBTQ people. And surely some fear. And fear can kill the desire to listen.

You specifically say in your book that “the first and most essential requirement [to building a bridge] is listening.” But how is that possible when it feels like each group is speaking a different language? The church is thousands of years old, and operates as such; LGBTQ parishioners are proposing radical change.

That’s true sometimes, but at heart, both sides desire to speak the same language: that of Jesus Christ—what he said and did in the gospels. And one thing Jesus said was that people should be loved and made to feel that they are loved. And he would reach out to those who felt that they were on the margins. So that’s a common language that I hope we all understand. The gospels should be our vocabulary.

Your book discusses the need to construct a two-way bridge, where each group needs to show the other respect, compassion, and sensitivity in order to foster a healthy relationship. In your mind, though, are the “lanes” of equal width? Shouldn’t the church do more of the heavy lifting?

Yes, I agree 100 percent. The onus is squarely on the institutional church. Over the past few years, I’ve heard the most appalling stories from LGBTQ Catholics, who have told me about priests saying ignorant, hateful, and downright cruel things either in person or from the pulpit. And public comments from bishops also make their way to people in the pews. In other words, it’s church leaders who have made LGBTQ Catholics feel marginalized, not the other way around.

So it’s important to say that it’s the responsibility of the institutional church to take the first step in this dialogue. For example, if a bishop wants to arrange a listening session with LGBTQ members of his diocese, that’s up to him. If he wants to meet one-on-one with LGBTQ Catholics, that’s up to him. If he wants to celebrate a welcoming mass, that’s up to him. The LGBTQ community most likely won’t be able to make these kinds of things happen. They can work in other ways, of course, but the opportunity for more formal dialogue and “encounter” will have to come from the hierarchy.

But how can LGBTQ Catholics begin to trust and respect the church when there continues to be a sense of exclusion and erasure from its leaders?

That’s a real challenge, and it will be hard for many LGBTQ people to hear that. But I would suggest that respecting the institutional church, and treating bishops with dignity is part of what it means to be Christian. Even if some LGBTQ people feel that a particular bishop or priest is an “enemy,” we need to remember that Jesus asked us to love our enemies. What’s the alternative? Demonizing them? That seems to just perpetuate the cycle of hatred and mistrust.

You essentially say that prophetic speech shouldn’t be combative. But wouldn’t you agree that being somewhat confrontational in the past has helped advance LGBTQ equality?

Yes, confrontational speech and actions have enabled advances for all sorts of groups. And sometimes that has a place in the church. But I’m speaking from a practical point of view. My sense is that with bishops, respectful conversation simply works better.

I’ve been in touch with the father of a gay son who meets once a month with his local bishop, who’s not particularly open to these issues. Over time, though, the bishop has come to understand things in a new way. So I ask: What’s more influential in the long term? Protests at his cathedral or this? It’s an open question, but in my experience, the gentler approach gets more results.

You ask the LGBTQ community to give the church the “gift of time.” Do you think full inclusion is possible in our lifetime?

Yes, I do. Look at the changes that have happened in just the last few years, since the election of Pope Francis. You have him saying “Who am I to judge?” which addressed not only gay priests, but gay people in general. You have him speaking in his apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia about reminding LGBTQ people “before all else” of their dignity. You have Cardinal Blase Cupich, archbishop of Chicago, reaching out specifically to LGBTQ people after the Orlando shootings. You have Cardinal Joseph Tobin, archbishop of Newark, [New Jersey], welcoming an LGBTQ group to his cathedral. And you also have Cardinal Tobin and Cardinal Kevin Farrell, a Vatican official, as well as Bishop Robert McElroy of San Diego, endorsing my book. That would be absolutely unheard of just a few years ago. So full inclusion is possible, and, as for time, I think it’s speeding up.

How far along do you think we are, realistically, in terms of building that bridge?

We’re still taking our first tentative steps. Before, you had to use coded words like “spectrum” or “welcome” when it came to LGBTQ outreach groups in parishes. Of course, in some dioceses and parishes, you can barely use terms like “gay” or “LGBTQ.” And others are pretty far along on the bridge already. The better question may be, “Who keeps the bridge from collapsing?” The answer is the Holy Spirit, who desires unity, welcome, and love. We have to do our part, especially listening to the experiences of our LGBTQ friends.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

Follow Xorje Olivares on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Jesus, Mary Magdalene, Judas Iscariot, and some fourth wheel at the Last Supper (All photos by Paige Taylor White) -

Screenshot: Electronic Arts -

Protestors against Italy's surrogacy ban. (Photo by Simona Granati – Corbis/Corbis via Getty Images) -

Sancta at Stuttgart's State Opera