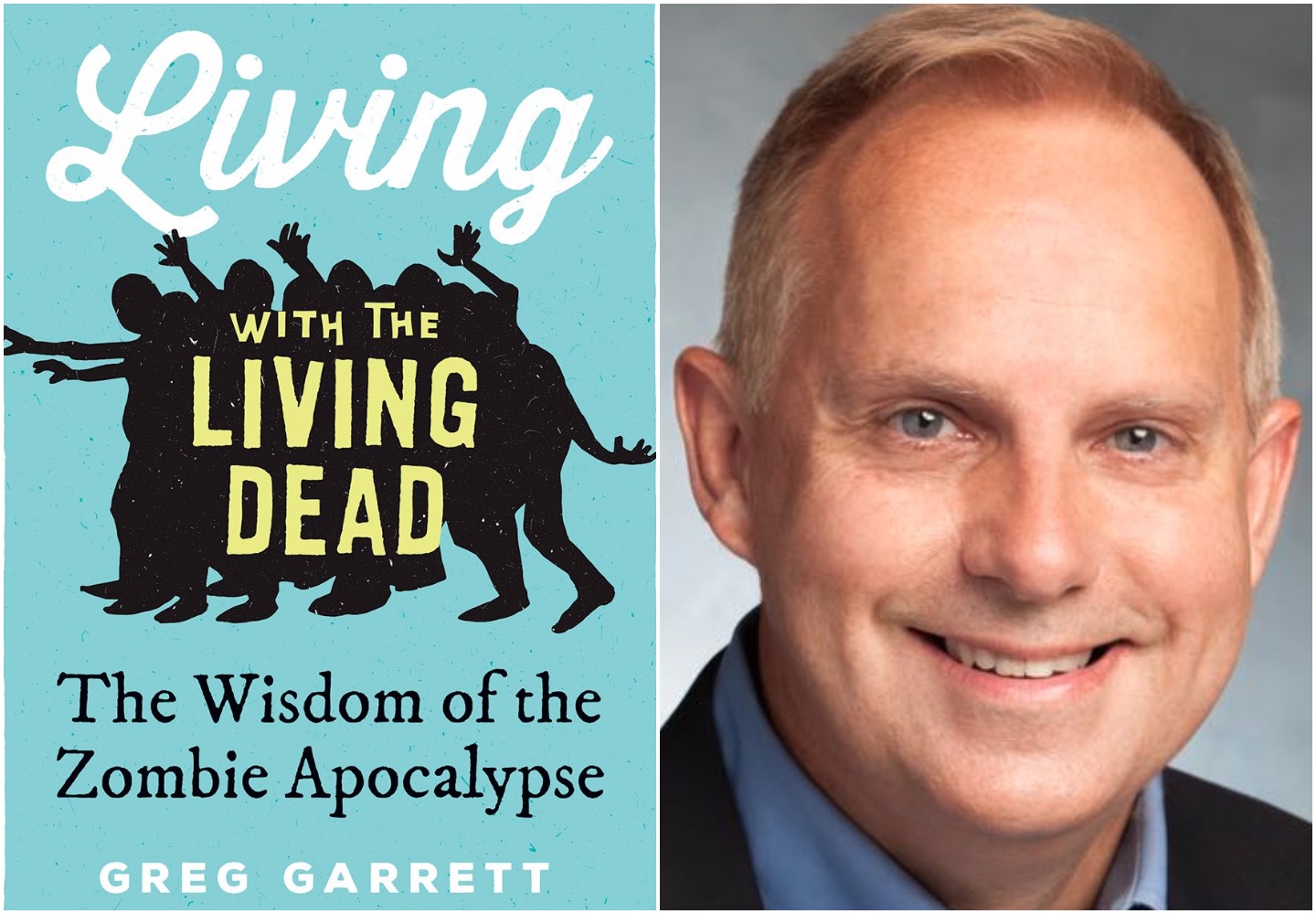

Greg Garrett is one of the last people you would expect to have written a book about zombies. He is a religion and culture writer whose ideal day includes a hike through the mountains and “a good church service that concludes with taking the Eucharist.” Garrett doesn’t go out of his way to be surrounded by gore. But his new book, Living with the Living Dead: The Wisdom of the Zombie Apocalypse, which was published by Oxford University Press earlier this month, is immediately unlike the dozens of manuals on the undead that have flooded the market over the past 20 years. In fact, accounting for that explosion, and reckoning with what it might mean for contemporary American culture, is part of the book’s mission.

In Living with the Living Dead, Garrett dissects such fare as 28 Days Later, The Walking Dead, George Romero’s horror films, Game of Thrones, and Shaun of the Dead as though each is a moral fable—which, according to Garrett, is what they are. “Steal[ing] past ‘watchful dragons’ was how C.S. Lewis described the way fantasy could lay bare certain deeply rooted ethical questions. Living with the Living Dead steals past watchful corpses. Garrett spoke to me over the phone from Paris, where he is currently the theologian-in-residence at the American Cathedral.

Videos by VICE

On Daily VICE: How to Survive a Zombie Apocalypse:

VICE: You write in your book how artistic traditions like the memento mori and the danse macabre existed to process the reality of death.

Greg Garrett: If you look at some of those woodcuts and fresco paintings, what typically happens is that Death reaches out with one bony paw and yanks the living off to their just reward, whether they’re an emperor, the pope, or a farmer in a field. So I was thinking about this in terms of a certain hostility toward death. Death comes to the forefront of art and culture whenever humankind faces some kind of stress point, whether it’s the Black Death or WWI—9/11 is one of those flash points for us.

How did things get so out of whack that we ended up with so many zombies post-9/11?

On one hand, zombies do represent that threat level, the thing that’s keeping us up at night—refugees, terrorists, the Zika virus, the people in the opposing political party. But zombies also give us an agency because it is also a monster with which you have some modicum of success: You can go one on one with a baseball bat and possibly survive. I was also thinking about this anti-immigrant sentiment that we’ve seen in the West and how this fits in with the zombie monster. It can go across a variety of cultural platforms. If my worries are X and my conservative friends are worried about Y, we’re both still worried, and we both still need something that can stand in metaphorically. You can have Republican zombies, Democratic zombies, socialist zombies. Everyone gets something out of that transaction.

And there’s the idea that actual death is less proximate than living death, the drudge we live in where we’ve lost all sense of adjacency to others.

What both Dawn of the Dead and Shaun of the Dead remind us is that it is possible to be locked into a kind of repetitive life where there is not much difference between you and a walking corpse. In Shaun, it is played for laughs as the characters don’t realize they’re dealing with zombies, everything looks so familiar to them: teenagers banging their heads to their Walkman, the girl working at her grocery checkout job, just doing the same repetitive things. One of the spiritual lessons we can carry from the zombie is that they remind us to be mindful of the present moment. If you want to be better than a living corpse, here are some things you might change.

“If my worries are X and my conservative friends are worried about Y, we’re both still worried, and we both still need something that can stand in metaphorically. You can have Republican zombies, Democratic zombies, socialist zombies. Everyone gets something out of that transaction.”

What about zombies and the family unit? In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and its imitators, the test is for the family to endure, which would appear to be kind of a conservative, “Morning in America” kind of reactionary-ism, the idea that traditional family values are the bulwark against disorder.

I’m very drawn to the idea of community as expressed in the idea that we are made for more than pragmatic zombie survival. The family will keep us alive, but what we find in The Walking Dead, for example, is that people become their best selves when they’ve come to think not just of how people can help us survive but help us thrive.

Is it our terror of connecting to other people that partly manifests in these kinds of zombie stories?

We are theoretically connected in so many ways, and yet as we look around and people seem more disconnected and isolated than ever. Zombies reflect that because they are locked out of the world around them, a reminder of the terrible loneliness that can happen to us if we fail to reach out.

As a theologian, you must be interested in the difference between resurrection and reanimation.

And the difference between Jon Snow, who can come back as the person he’s meant to be, and the White Walkers. The Christian faith understands the resurrection of Christ as a kind of cosmic reboot. In this cosmic circle of decay, Jesus offers a new understanding of existence, where death no longer holds sway over everything. But you don’t have to be religious to want to live in a world where hope has more power than despair. We see this in the George Romero films where humankind is on the way out, and we are done for. But in another kind of story, like Game of Thrones, death is a way to new life.

What about the risks of living in an apocalyptic mindset, as we increasingly seem to be doing?

We have to balance that with a healthy awareness that whatever threats we’re facing, we as a species will probably survive them, and the planet is going to go on. And that steps have to be taken to make that possible for people besides ourselves. That’s why I think we have to engage our critical faculties and look at this set of stories we have about how a group of people might do that at the end of the world. How do I live a life that is less acquisitive, a life that screws up the planet less? And what are immediate steps I can take? How can I change my practices? What are some things I can live without? If we are prompted to think of the present by “end of the world” stories, so much the better. Meanwhile, here we are struggling on and trying to do it better.

How do we keep from becoming zombies ourselves—or worse, the militarized survivors who have become monsters in the name of keeping order?

These stories do lend themselves to some progressive readings. One of the things that makes the zombie apocalypse such a powerful post-9/11 narrative is that it asks, “What are you willing to do to survive?” and “What are you willing to do to protect those you love?” Some really heinous things, as it turns out, and that is very much the reality we tripped into, where we decided on the vigilante impulse in protecting our country. The zombie apocalypse asks, “Is it worth surviving in every circumstance? Is it possible that some of the things we do to survive might make our lives no longer worth living, as we discover we’re no longer the ethical and compassionate human beings we thought we were?” I think that one of the things that has made shows like The Walking Dead so pervasive is that it allows us to ask questions that, in the States, we did not have the opportunity or willingness to ask in the early days of our response to the war on terror.

What can zombie stories tell us?

We need to ask hard questions about the ultimate good of cultural assumptions like acquisition and consumption. None of those things equate us becoming better human beings or more loving partners. What these stories allow us to do, in the words of [Walking Dead creator] Robert Kirkman, is imagine how in a world where the dead walk, we might have to learn how to live for the first time. We have to question the things that we thought were important because things have clearly turned out so terribly. If we think about what is truly important in life, we come back to Thoreau and Walden Pond. It turns out that what is necessary is a whole lot less and a whole lot different than what our culture tells us, and those are the things we should be living for. It’s a place where there’s an intersection between faith and the secular and zombies.

Recent work by J.W. McCormack appears in Conjunctions, the Culture Trip, the New York Times, and the New Republic.

Living with the Living Dead: The Wisdom of the Zombie Apocalypse by Greg Garrett is available in bookstores and online.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshots: GSC Game World, Xbox Game Studios -

(Photo by cyano66 / Getty Images) -

Casper -

(Photo by CRAIG TAYLOR / Getty Images)