Main image: ‘Garry’s Mod’ screenshot courtesy of Garry Newman

This article contains story spoilers for The Beginner’s Guide.

Videos by VICE

A dream reel superimposes the outline of a gangly, suited man over a procession of ephemeral images. The apparition of an Anti-Mass Spectrometer whirrs into being behind him before ebbing into darkness again. The image is replaced by the immense mechanized interior of an unknown building. “Rise and shine, Mr Freeman,” he says, his voice the toll of a bell you never wanted to hear again. “Wake up and smell the ashes.”

For many, this was the first glimpse of Valve Corporation’s Source engine. Developed to succeed their flagship GoldSrc engine—itself a heavily modified version of the Quake engine—Source debuted with Counter-Strike: Source a few weeks before the release of Half-Life 2. It would be the latter game that put the engine in the possession of pretty much every gamer on the planet.

Released in late 2004, Half-Life 2 needs little introduction. Its vast literary pretensions juggled so many balls that it will take a truly inspired team of writers not to drop any should a sequel, a third Half-Life proper, finally emerge. The game also drew a legion of expert modders to Source, says Garry’s Mod developer Garry Newman. “It did a lot of stuff I’d never seen a PC engine do before,” he tells me. “It had refraction, actual working physics, real-time lighting, rope physics.”

At its core, Half-Life 2 was a corridor shooter, but it was one that assailed players with beautiful panoramic vistas to stop for a minute and get lost in. The physics puzzles and the ingenious gravity gun demanded a very deep level of interaction with the environment, in contrast to comparable games released that year. Halo 2 pillaged sci-fi cinema in its cutscenes and designs to hide its narrowness, while Doom 3 used cheap pop-up scares and “no duct tape on Mars” (a reference to how there was no way to attach a flashlight to your weapon) to make the environment a constant threat. Of the three, Half-Life 2 has dated the least.

“One of the things the Source engine does very well is boxy, linear corridors.” — Davey Wreden, The Beginner’s Guide

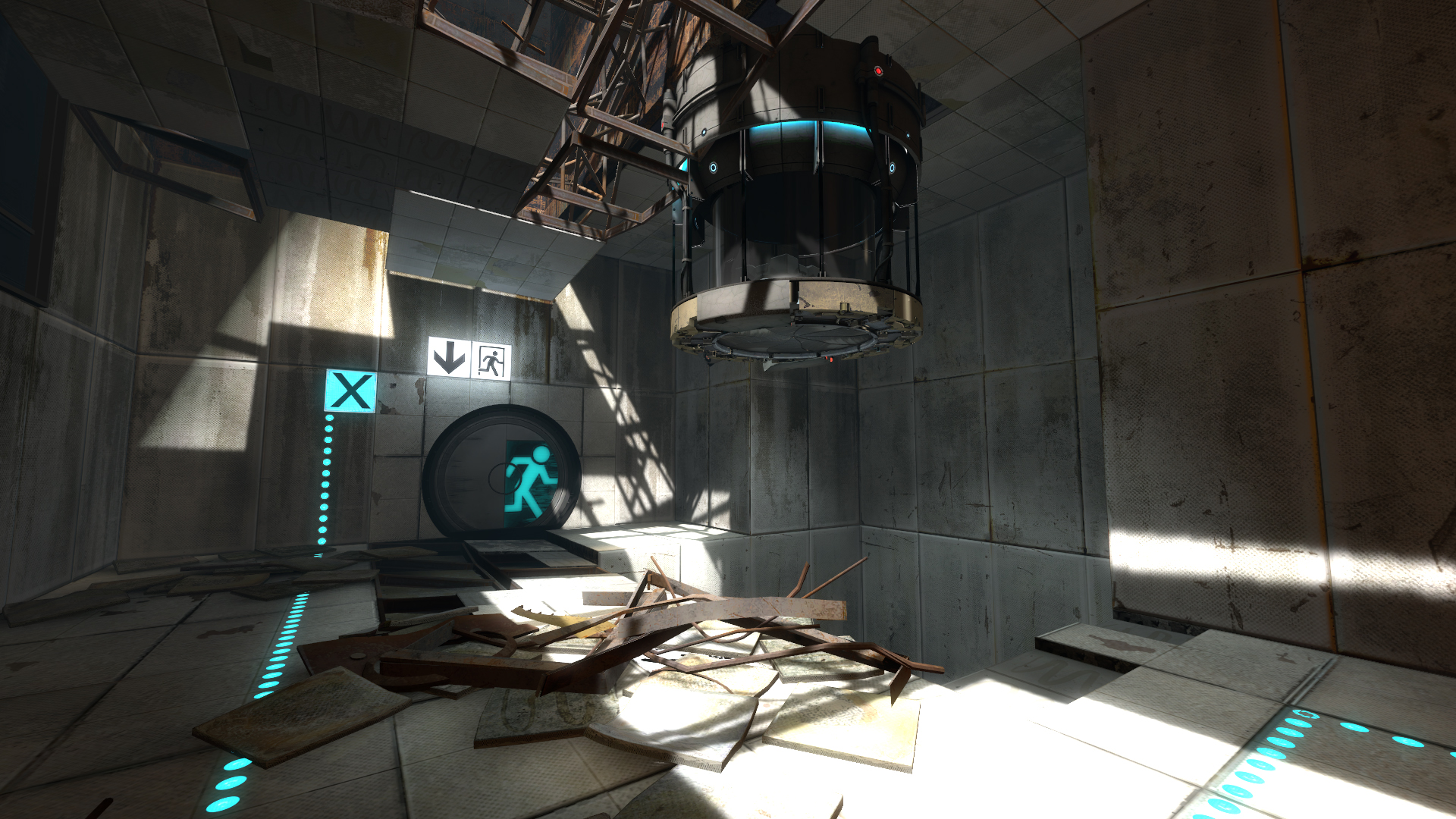

One of Valve’s biggest innovations with the Source engine arrived in 2007’s The Orange Box compilation: the Portal series. The portal gun is one of gaming’s most inspired devices, but it’s driven by limitations surrounding it. As Davey Wreden would point out in his chilling Source-powered 2015 narrative meta-game The Beginner’s Guide: “One of the things [the Source engine] does very well is boxy, linear corridors.”

The Portal games thrive on their own boxiness. As the mute heroine Chell, you’re forced to navigate one boxy test chamber after another, while a barrage of demoralizing vitriolic taunts are hurled at you by a malignant and witty AI.

The original Portal is an archetypal corridor game in the sense that there literally is no other objective. There’s nothing to shoot and no vehicular sequences, quests or mini games. You simply have to find the hidden corridor to get from A to B and into the next room; but that thought never crossed my mind once as I played, so deeply was I immersed in the fabric of the game world around me. The formula would be refined with the addition of a mind bending co-op mode in 2011’s Portal 2.

Spoilers below for The Beginner’s Guide.

‘Portal 2’ screenshot courtesy of Valve Corporation

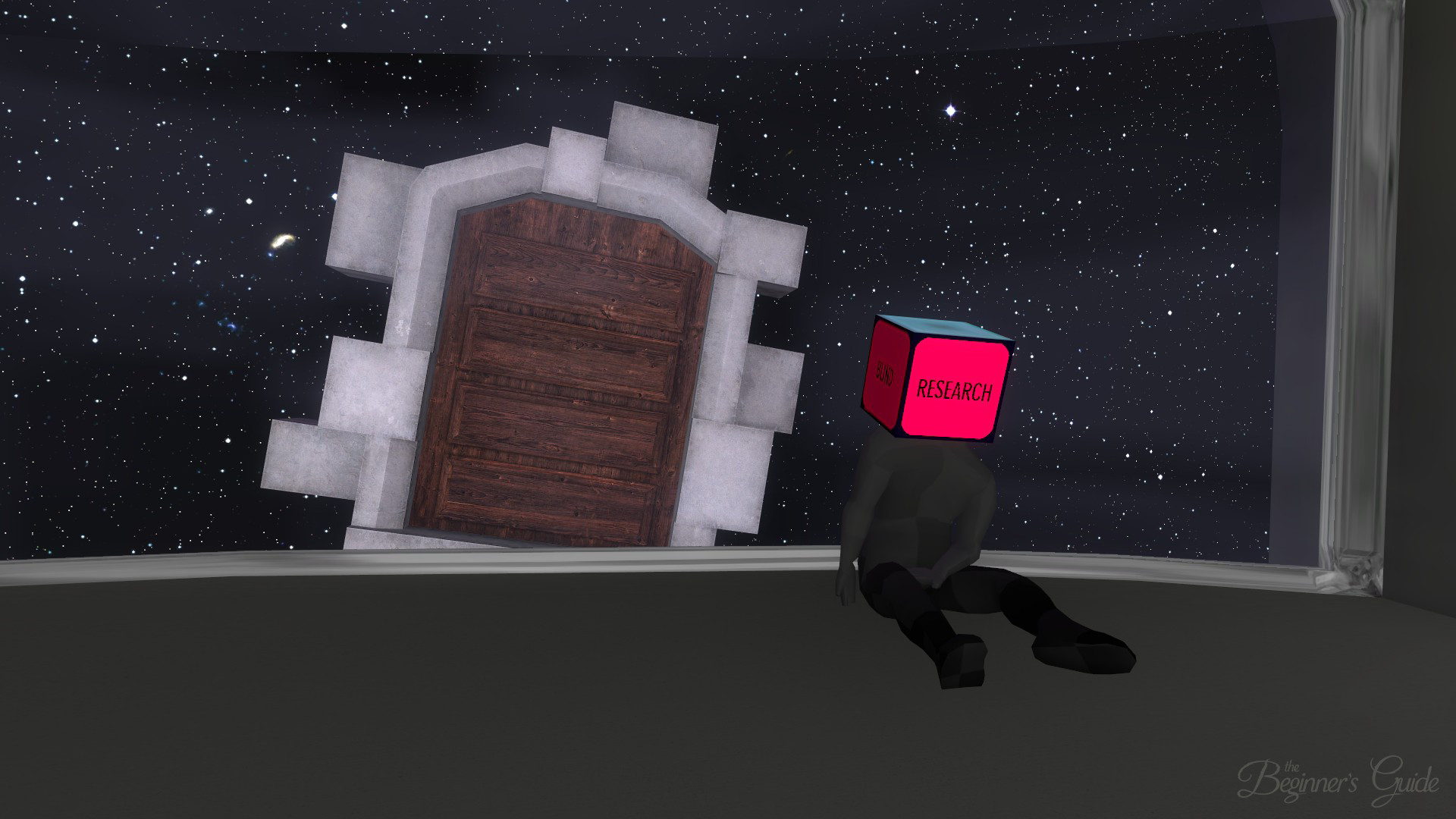

It isn’t just Valve titles that highlighted the manifold possibilities of Source. The aforementioned Wreden rose to prominence as an indie developer after the success of his narrative game The Stanley Parable, originally a Half-Life 2 mod, in 2011. His next title, The Beginner’s Guide, is his finest. Narrated by Wreden himself, it’s a metafictional masterpiece that sees you exploring the hard drive of a game developer named Coda, whose (“playable”) unfinished ideas on the Source engine each comment in some way upon the objective-based nature of gaming. Some of the games are less than a minute long and have no discernible objectives; others are completely unsolvable, unless Wreden delves deep into their coding for you.

Throughout the game, a fictionalized Wreden acts the smitten fan, constantly trying to interpret the meaning of Coda’s abstract creations while considering him to be a great, unknown genius. The short game’s profound beauty lies in its storytelling and a troubling twist.

‘The Beginner’s Guide’ screenshot courtesy of Everything Unlimited Ltd

Its story of a developer lost in his own unfinished creations, told from beneath puzzles, is one that can only be told through the medium of games, and one wonders how much of its impact would be lost if the game was built on a more detail-heavy engine, like Unreal 3 or 4. The Beginner’s Guide was made to feel game-y, and the employment of the Source engine made it all the more powerful in its visual simplicity. It may have been one big, corridor-driven narrative, but it got gamers thinking deeply about what lies beneath when you play. It got you questioning why you expect what you do from games in the first place.

Beyond the form-redefining indie and blockbuster titles, Source leaves behind it a modding legacy richer than any other engine. Like GoldSrc before it, Source proved to the industry once again that fans could make titles to compete with corporate developers. A fan-made reboot of the original Half-Life called Black Mesa provoked a wave of nostalgia amongst zealous fans. But Source’s crowning achievement in the modding community is Garry Newman’s Half-Life 2 mod, Garry’s Mod.

“Why would the developer let you create new missions, weapons, characters and tools when they can spend a couple of weeks doing that and sell it as DLC?” — Garry Newman, Garry’s Mod

A sandbox in the truest sense, Garry’s Mod has now sold over ten million copies. It’s a powerful statement in gaming’s ongoing historical narrative that a game with no objectives other than what the players create themselves can outsell classics like Tomb Raider 2.

“I’ve always thought my job is to give players the tools and to get out of the way and let them do what they want,” Garry explains. “[I wanted] to make them not reliant on me as a developer, to give them new things to play with, to entertain each other with new games and ideas.”

Garry’s Mod wasn’t the first sandbox mod for Half-Life 2. That honor goes to JBMod, which Newman freely admitted in a Reddit AMA was the reason for Garry’s Mod‘s existence. Vying to outdo JBMod led Newman to feverishly code new updates and improve his product. GMod soon took on a life of its own propped by a community who relished the infinite possibilities the game offered.

‘Titanfall 2’ screenshot courtesy of Respawn Entertainment/Electronic Arts

When asked whether sandbox gaming is something that can be refined further by developers, Garry says: “I don’t have high hopes. I feel like game designers are incentivized against that nowadays. Why would the developer let you create new missions, weapons, characters and tools when they can spend a couple of weeks doing that and sell it as DLC? It hurts my brain to think what my life would be like now, if Valve had the same attitude towards modding.”

With 2016’s Titanfall 2 running on a heavily modified version of Source, it’s clear that there’s mileage left in the aging engine. Valve will no doubt refine its successor, Source 2, for their future flagship titles, but the original Source will always be a snapshot of a truly progressive time in gaming. Today, Source games are generally starting to look curiously retro, but that’s something that can be expected of an engine which still retains parts of the Quake engine deep in its coding.

Related, on Waypoint: One Man’s Quest to Let People Play Games on Their Crappy Computers

“The boxiness of Quake and Source engine games is a weird thing,” Newman says. “You think as a player you want more detail, you don’t want rubbish everywhere, broken surfaces. But the truth is that a lot of the time this extra detail can confuse the eye and be detrimental to gameplay. You can see this in the popular Counter-Strike maps. They’re not all ruined buildings with rubble everywhere. They’re boxy, predictable corridors.”

Perhaps his success, and the success of Source titles in general, is down to the engine’s archetypal game-y-ness, reminding us at every turn that there are certain things that gaming communicates better than other visual and technological arts. As graphics get better, the demand for games to be interactive movies has never been greater. What Source titles achieved is still hard for a lot of contemporary games to pull off: they often made us forget that the rich worlds we were traversing were really just gigantic corridors.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: SNEG -

-

-