The most shocking thing about Sarnia, Ontario’s “Chemical Valley” is that people actually live there.

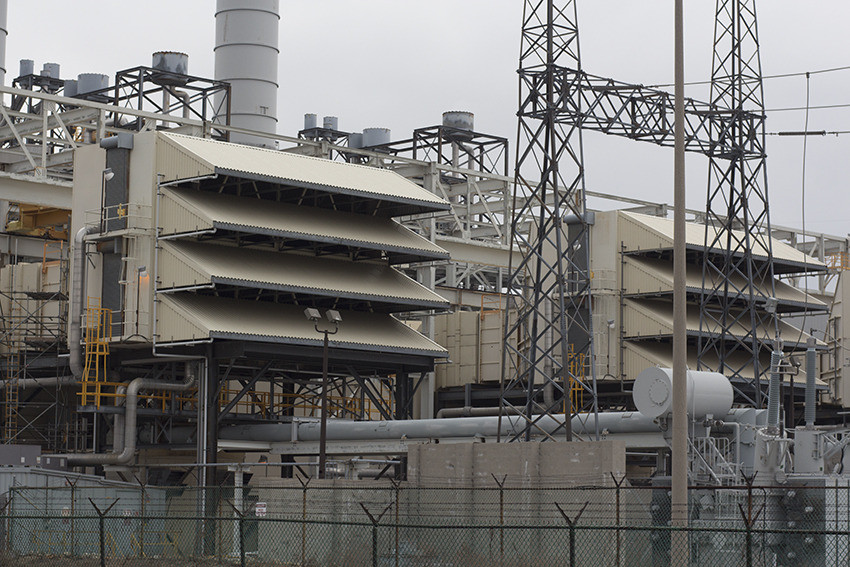

Collectively forming a posthuman landscape, more than 60 oil refineries and petrochemical plants—40 percent of Canada’s total chemical industry—operate within 15 miles of the valley. The air is among the most polluted in North America, carrying with it an unmistakable chemical stench. It is a toxic stew of sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, toluene, benzene, styrene, mercury, lead, nickel, etc. Visitors are advised to wear chemical masks or respirators.

Videos by VICE

The premise of the Toxic Tour, the first-ever walking tour of Chemical Valley, was absurd. Associated with Idle No More, a First Nations’ rights group, the tour brought pedestrians to a place where they are clearly not meant to be—a landscape of massive, toxin-emitting industrial structures. It is the type of place most frequently experienced from within a car with windows rolled up, though the valley’s toxic stench pervades even a closed vehicle. The valley’s main throughway, Vidal Street, is typically congested with cars, trucks, and tankers—though, ironically, this same road contains the only bike lane in South Sarnia. The bike lane is part of a wider, half-assed effort on the part of the city and its chemical giants to pass off the valley as a healthy place: bus shelters line the area with the message “Think Green, Take the Bus,” while a chemical company’s parking-lot sign encourages employees to “Stay Fit, Walk Farther, Live Longer.”

Further along the tour, the polite pretence of green-washing the valley is abandoned completely. Sandwiched between massive Dow Chemical, Suncor, and Shell facilities is Aamjiwnaang, a First Nations reserve with a population of about 850. The reserve is surrounded on all sides by refineries and petroleum facilities, many of which operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Its population has grown accustomed to living inside an industrial nightmare. About half of Chemical Valley’s industrial facilities operate within three miles of the reserve, with some homes and community facilities (a basketball court, a baseball diamond, the band office, and for many years a day-care center) immediately next door to refineries. “I can see Shell from my window,” Ada Lockridge, an Aamjiwnaang resident, told me.

In true apocalyptic fashion, every Monday at noon the chemical plants test their chemical-leak warning sirens—an emergency system rarely used when an actual emergency occurs. According to Vanessa Gray, an Aamjiwnaang band member whose family moved off the reserve because of health concerns, sirens only go off “when a leak is reported. It’s not very often that leaks are actually reported, they happen all the time. People know because of the flares getting really big. They know when the smell is very strong, or very different in the air.”

The Aamjiwnaang First Nations’ burial grounds, physically severed from the reserve by a massive Suncor facility, were initially surrounded by Suncor surveillance cameras that recorded community burials—though some cameras were withdrawn due to community protest. Warning signs mark the buried oil and natural-gas pipelines that run throughout Aamjiwnaang, coming up to vent in peoples’ lawns and near children’s playgrounds. Aamjiwnaang’s waterfront, overtaken by Shell facilities, looks out to refineries and coal burning plants across the US border. In a part of the St. Clair River, where liquid runoff is released by Shell, the water maintains an irregularly high temperature, often releasing steam and a strong gasoline odor.

While Sarnia at large suffers from exposure to airborne toxins, with higher rates of hospitalization than the rest of Ontario, the problems are compounded in Aamjiwnaang. The reserve is a sort of industrial sacrifice zone, continuously exposed to pollutants known to cause cancer, cardiovascular, respiratory, developmental and reproductive disorders. Aamjiwnaang has, for instance, a 39 percent rate of miscarriage and an anomalous-birth ratio of two women for every man born (as opposed to national average of approximately 1:1). Vanessa Gray explained to me that the health of both herself and her siblings improved after leaving the reserve, even though she moved just down the road to Corunna and later to downtown Sarnia. “A white community is not surrounded by this. Stephen Harper doesn’t live next to this,” she said.

Aamjiwnaang’s out-dated welcome sign, which reads “Population: 1,800,” betrays the truth of its endangered population. Many have abandoned the reserve due to health problems, often leaving behind elderly family members. Others stay because they cannot afford to leave. But a community continues to exist in this polluted wasteland—life goes on in toxic air. For the toxic tour, many tourists (myself included) came prepared with opulent respiratory-protection systems, while only a few Aamjiwnaang residents bothered with chemical masks. Vanessa Gray explained, “Seeing those facilities every day, it’s not a big deal and we’re so used to being abused. It’s too hard to think about it every day.” From the perspective of an outsider, it is difficult to imagine seeing a place like this as anything other than an enlivened tragedy. Yet, when looking at my photos of the reserve, Ada Lockridge criticized, “I wish you took photos of some of the nice houses too.”

Follow Michael on Tumblr.

More from Canada:

Why Canada Needs Sasquatch

What Exactly is Idle No More?

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano

Michael Toledano