In 1958, in a shitty neighborhood of Lincoln, Nebraska, Charlie Starkweather, a disgruntled teenage tough who was mad at the world, and his 14-year-old girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate, murdered Caril’s disapproving family and hit the road on a murderous two-month odyssey. They killed seven more people along the way (it is unclear just how complicit Caril was in the killings, as she claimed she had been kidnapped by Charlie), before they were captured in Wyoming. The story shocked the nation and became the stuff of myth and legend. The references to it in popular culture are far reaching. One of the most well-known examples is Terrence Malick’s Badlands.

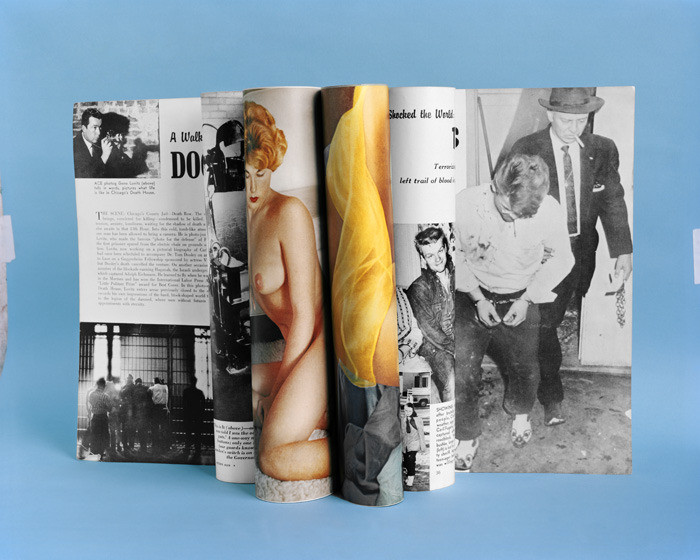

It was via Badlands that photographer Christian Patterson discovered the case. Struck by the story, Christian subsequently made a photo series, entitled Redheaded Peckerwood, which was hailed by many as a shining example of the potential that photography books held. The series and the book are conceptual, highly ambitious, visually striking, and thematically absorbing. It loosely follows the storyline of the spree, using the story as a springboard to creative inspiration, blending fact and fiction, art and artifact, and the boundaries between conceptual and documentary photography. The book’s third edition will be released by MACK this month, so we sat down with Christian to discuss his work and the story.

Videos by VICE

VICE: Congrats on the third printing. I know there were new elements added in the second edition, are there new things in the third one as well?

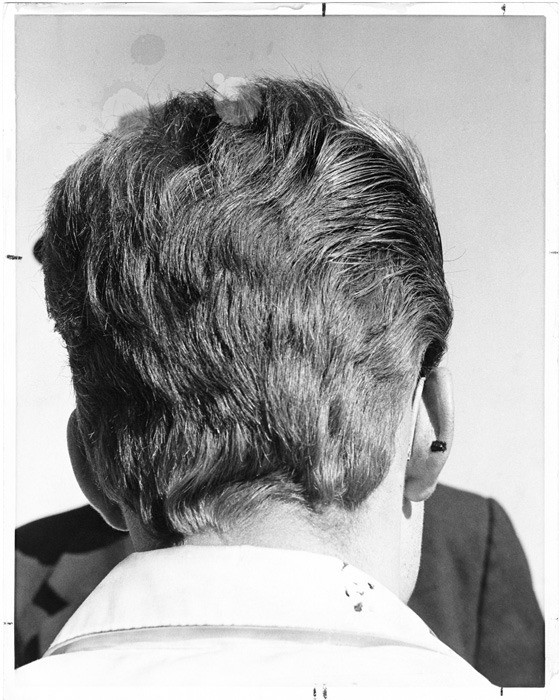

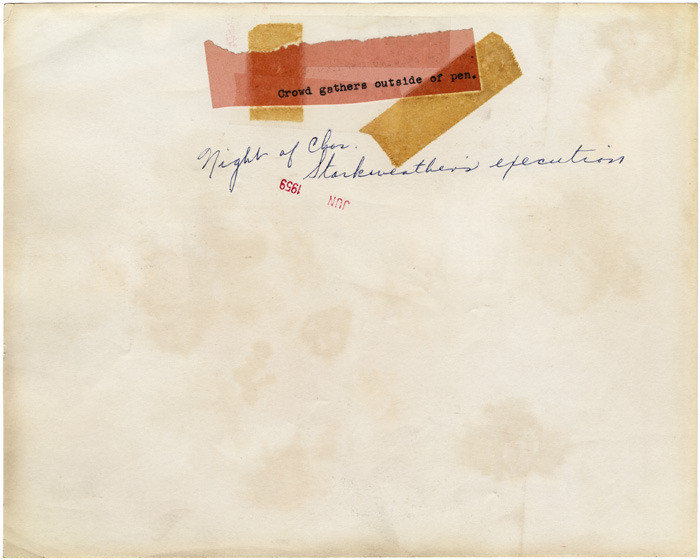

Christian: Yeah. It’s interesting, the story that the work is based on is a fairly well-known story nationwide or even around the world, but in Nebraska especially, it’s one of the biggest news stories in the history of the state. It’s become local folklore there in a way, and as people have become aware of the work that I’ve made, they’ve come to me with stories and discoveries. I found this man who was working on an old house in Lincoln, tearing the house apart and renovating it, and when they tore into one wall, they found a stash of negatives and prints, many of which I’ve never seen before, crime scene photographs and police photographs. Some of them were far too risky for me to include because I’d never wanted to take too sensational of an approach with the work, but there is one crime scene photo that is included in the third printing. You can see the shoe coming out from under the bed and I do think that there probably is a body attached to that.

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

In addition to that story, there have been other things that have come to me over time and so I’ve had a few additional appropriated images from various official archives that I’ve found since I first made the book. Those are contained in the section at the back of the book where the book begins to return to the archives. With some exceptions; there are photographs in the book that may appear to be old but are not.

One of the most important parts about the book seems to be the blending of what is evidence and artifact with what is influenced by those artifacts. You might call it poetic license in a sense. I’m interested to know how dedicated you are to the idea of keeping those a secret. Are you attempting to create your own mystery out of an older one?

Yeah, that was my intention with the making of the book, to add some mystery and have the book serve as a visual crime scene, a collection of clues that someone could look at and maybe find their own way. It’s a tricky balancing act, presenting the work in that way, but I also included the booklet that helps to explain what’s going on. [Editor’s note: a separate small, stapled book accompanies the hardbound book that contains both background on the killings as well as an essay on Christian’s artwork.] But by having it be its own separate piece that can be removed from the booklet, the reader can decide whether or not to read it.

I do, at times, share some of the different stories involved in the book or the making of the work, mainly when I am asked to give a talk. I usually share selected stories along the way. Again, it’s a tricky balancing act because some of these stories are interesting and quite fascinating and once you get started sharing some of those stories, it can be difficult to stop.

I love how the original story is already so enigmatic, but learning about your mixture of fact and fiction, and subsequently wondering which is which, when looking through the book, adds another layer of mystery on top. For example, I was drawn to the image of the storm cellar (in the gallery above). You don’t have to tell me if it was or wasn’t the actual spot where Charlie and Caril Ann hid, I won’t ask.

Yeah, earlier today, I ran across a review of the book and they were under the impression that a certain image in the book—this image of the bottle of Oregon Trail Black Cherry Soda—was an appropriated image, but this is actually an example of an image that appears to be old but that is in fact something I made to look old. I painted around the bottle in the same way that a photojournalist or someone that was retouching the photograph or a newspaper would have done. I want to confuse the viewer or open the door to let there be that blending, that mixing, that blurring of the lines between fact and fiction, past and present.

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

In the moment that I ran across that again and reread that, I initially had this impulse to reach out to the guy and say, “No, that’s not really the case,” but in the end, it’s actually better. It’s fun to know that there is this confusion out there. It’s a little tough, because it’s an image that I created myself and I feel like I’m not necessarily getting credit for that, but in a way I am.

Another thing that is so striking about the work is how many different styles of imagery and material you use. There’s the photographs, archived documents, the sculptural stuff like the tire or the painted signs, and then you introduce elements that force you to interact with the book, things that you have to move and lift. It’s a book you clearly have to spend time with and revisit to understand. How much of that did you think about when you were creating the book? Were you setting out to make a piece that was confounding, that challenged the viewer and made them work to understand it?

When I initially started the project, that’s definitely not what I had in mind. I began by making much more straight work, more heartfelt documentary photography. I initially set out to do something similar with Redheaded Peckerwood in that I thought that I knew the story and knew that it involved the element of travel and it included this trail that I could follow. I thought that I would just follow that path and make photographs along the way, document this landscape that was charged by the story. I could’ve made good images, and that for some people or some projects, could have been enough.

When I first began working on all of this, it was nearly 50 years after the fact. Early on, I quickly realized that there was only so much stuff that actually remained out there in the real world that I could simply revisit and document. I hit a brick wall and was confronted with a real challenge. I had to make the decision whether or not to try to continue making this work or to abandon it. If I was going to continue, I would have to find new ways of making the work, or illustrating the various facts that I knew of, or the ideas that I had that were influenced by the facts. And that’s what slowly began to open the door and force me to find new ways to illustrate new ideas, to structure work with different materials.

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

At the end of my first trip, I already had this feeling of reaching a dead end, but my entire process always begins with concept and is usually followed by research. So, I decided to return to the research, and at the end of that first trip I went to a few of the local archives like the Nebraska State Historical Society and the Lincoln Journal and Lincoln Star, two local newspapers. As soon as I went into those archives, I began to see some of these materials and just how strong they were visually, how visceral they were, and how they felt close to the story. That excited me. I immediately felt that I needed to include some of this material in some form, but I also knew I had to do it in an artistic way. I had to incorporate these things and make something new or something on my own from it. I didn’t take it in one specific well-defined direction, there were all these other different pathways that began to emerge and I followed them all to a certain extent.

I began to disregard some of my earlier feelings about photography, the way that photography worked and notions of documenting truth and representation, and having to take a new position of not caring so much about what was what and where it came from.

Was that difficult for you or was it more of a feeling of freedom?

It was freeing. It didn’t take long for me. Again, I was faced with the decision to either stop now, or do this and enable the continuation of the work. Once I opened that door, it was very freeing not only for this project, but for my practice in general. I think that this is a way of working that I’m interested in continuing. I’ll keep on making photographs or even making more series that consist solely of photographs. But I think I’ll continue to work in this more multifaceted way.

I also read that you made this work over a five-year period. How does working on and living with a project for that amount of time influence the work?

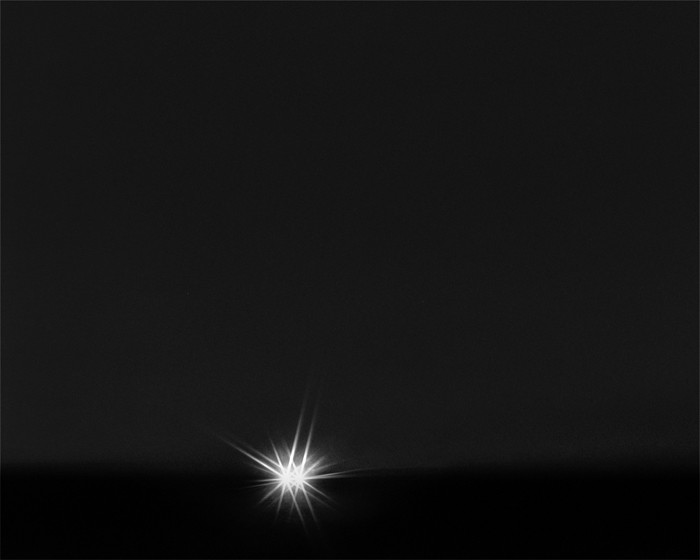

That was a reflection of the logistical situation, first and foremost. I was living in Memphis at the time and Nebraska was pretty far enough away. I had decided early on that to remain true to some extent to the story, to maintain some connection to the story or have some underlying veracity to the project, I needed to make the work in the same place, at the same time of year like Charlie and Caril Ann did. I wanted to visit these places and things that were part of the story were possible, but I wanted to do it the same time of year and to be in the same landscape and have the same feeling myself and have the same look in the work. That was probably the primary thing that influenced how long it took me to make this.

In addition to that, the difficulty of making the work and the time that it required, the research, the tracking down of various people and things, it allowed me time to spend with the work and continually reassess the direction that it was taking. I would spend between seven and ten days in Nebraska once each year and I would have the whole rest of the year to sit and analyze and ruminate on what I’d made.

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

My interests and influences as an artist changed dramatically during that time period. I began the work when I was living in Memphis and working with William Eggleston. It was a big early influence for me and he’s still one of my favorite photographic artists, but I also began to become interested in other photographers’ work and other types of art. I became much more interested in more conceptual and challenging work, things that weren’t as documentary in nature, and artists who were often working photographically and telling stories in much more indirect and even vague ways. I feel that Redheaded Peckerwood is work that walks the line between those two different ways of thinking and working.

You mentioned tracking people. In my own research, I discovered that Caril Ann is still alive. Have you ever thought about tracking her down and possibly taking a picture of her?

Yes, I was aware of that, and while I can’t say that the thought never crossed my mind, I never seriously pursued that. For one thing, I know that she’s actively avoided contact with people or public appearances.

She changed her name, didn’t she?

The rumor is that she changed her name or that she married someone and maybe changed her name in that way. I think she’s resurfaced once or twice in what is now roughly 45 years since she’s been out of jail, and one of those times she went on an early reality-type game show called Lie Detector [Editor’s Note: hosted by F. Lee Bailey]. The whole premise of the show is that people were invited to come on and take a polygraph exam. She was on the show, and they asked her some questions. They tried to ask her whether or not she was in fact guilty or whether Charlie kidnapped her, and she passed. The test showed that she was innocent.

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

There is still a lot of speculation, and I’m not sure what to think myself. I guess that’s one of the interesting things about the story for me, and the book. I tried to allude to that and there are a lot of pictures of her and things that are related to her, but I make no effort to point the finger or take a side. I didn’t think that meeting her would add anything to the work for me. A little mystery goes a long way, and I don’t want to destroy that. I have a feeling no one will ever hear anything about her again until she dies. Even then, I don’t think there’s going to be a great revelation.

Seems like one person’s word versus another’s.

Yeah, there are only a few people who know what happened. I guess they’re the two kids, the killers, and the victims. The victims, they’re all gone, and Charlie is long gone, too. I think that story is just going to die with Caril.

Hopefully, your work will help it live on.

Pick up a copy of the third pressing of Redheaded Peckerwood here.

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk

©Christian Patterson, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk