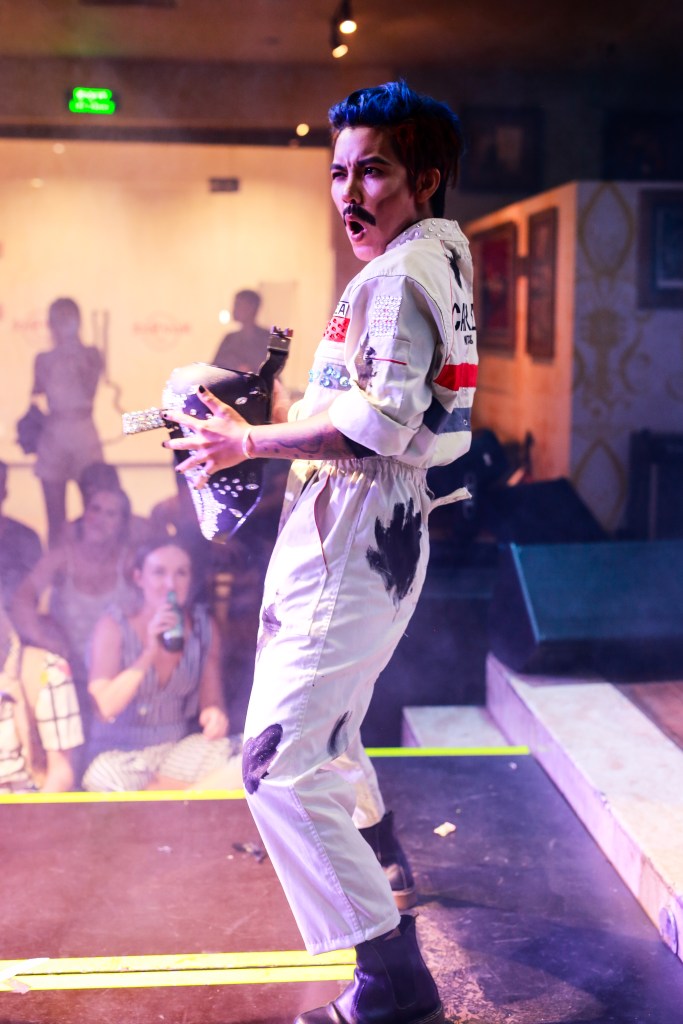

Lil’ Daddee struts onto the stage wearing a fake mustache and a boiler suit covered in grease stains. The performer picks up a large bicycle pump and carries out a suggestive routine for several minutes, pulling the long rubber hose back and forth between their legs as emphatic cheers rise above the music.

Lil’ Daddee is one of five drag kings battling it out in a test of “hyper-masculinity” at GenderFunk’s regular drag competition in Ho Chi Minh City. Nights like these have become a popular fixture in Saigon’s social scene—created in 2018, it provides “safe spaces for queer artists and all humans to express their sexuality, their gender and their own style of creativity,” according to organizers.

Videos by VICE

While most of the performers are from the LGBTQ community, the event has gained mainstream appeal, as its recent move to the Hard Rock Cafe in Ho Chi Minh City’s arterial Hai Ba Tung district indicates. Audience members are an eclectic mix of drag artists, queer folk, and couples looking for a fun night out.

Vietnam’s position on LGBTQ rights defies simplistic categorizations. Compared to its Southeast Asian neighbors, it is neither as progressive as Taiwan nor as punitive as Malaysia, where engaging in sodomy carries a penalty of up to 20 years imprisonment.

A history of suppression

After the country’s reunification in 1975, the deeply-embedded Chinese philosophy of Confucianism, with its traditional gender roles, was rejected by the newly installed Communist government—which required the collective effort of all Vietnamese people to rebuild the country. The effort coincided with a clampdown on sexual freedoms, with individual expressions of identity suppressed for the “collective good.”

By not mentioning people who did not conform to heteronormative standards of sexuality and gender, the legal system effectively ignored their existence.

While same-sex weddings conducted privately were tolerated, the first public gay wedding, attended by more than 100 guests was held in a Ho Chi Minh City restaurant in 1997, while the first public lesbian wedding was held the following year. The outcry that ensued forced the authorities to intervene and the marriage was promptly annulled.

In 2000, following confusion caused by the legal vacuum, same-sex marriages were officially outlawed. However, a quirk of the Vietnamese legal system allowed wedding ceremonies to continue, despite the prohibition on same-sex marriage.

As recently as 2002, homosexuality was described as a “social evil” by state-run media, on a par with drugs, prostitution and gambling. Any sexual deviation was seen as a foreign imprint, the lingering, toxic effects of colonial history and Western decadence.

In the early 2000s, the government called on organizations to “tighten state management to prevent the exploitation and the circulation of bad and poisonous information on the Internet.” Cyber cafés were regularly targeted to ensure adherence.

A recent paradigm shift

There have been “many changes in the nation’s physiognomy” over the last two decades, as Vietnam noted in its Socio-Economic Development Strategy 2011-2020 paper.

As a socialist-oriented economy with aspirations to become self-sufficient in the context of an increasingly globalized world, Vietnamese lawmakers see people as “the main resource and objective” whereby its development goals can be achieved. To this end, the paper stipulates a need to “guarantee human rights, civil rights and other conditions for people to develop comprehensively.”

Relaxed internet laws have helped provide answers and a sense of belonging to queer and transgender people, leading to the creation of online communities that have mobilized LGBTQ advocacy. With a commitment to human rights often made as a condition of foreign investment (take for instance this year’s newly-ratified EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement, EVFTA), several LGBTQ rights groups emerged—funded in large part by Western organizations and staffed, in many cases, by Vietnam’s elite youth, often returning to the country after an overseas education.

The first official Viet Pride celebration took place in 2012, with public events held in both Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, and annually thereafter. The climax of LGBTQ activism came in 2014, when same-sex unions were removed from a list of forbidden relationships in an update to the country’s Marriage and Family law. This was swiftly followed, in 2015, by the National Assembly voting to allow trans people the right to change their identities.

In 2016, while serving on the United Nations Human Rights Council, Vietnam voted to establish a mandate protecting against violence and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

The current scene is thriving

Nowhere else better demonstrates the country’s advancement towards LGBTQ rights than Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam’s largest city and the nation’s economic lifeblood.

Where traditional notions of sex and gender still persist elsewhere, in Saigon (as the locals still refer to it), queer and trans culture have become ubiquitous. Publicly-acceptable spaces for trans people used to be limited to performative roles, such as at funerals, where trans women could make a living as entertainers tasked with lifting the spirits of mourners, as well as the spirits of the recently departed.

Today, many trans and queer folk are part of the social fabric of urban life, and how people identify is no longer a matter of public concern. The apparent normalization and visibility of non-binary people in urban areas are perhaps one of Vietnam’s most underrated LGBTQ achievements.

This normalization has also taken place on television screens and newspapers. In recent years, programs like Come Out and Just Love have also helped to promote diversity and understanding of the LGBTQ community. Picking up a state-controlled newspaper, it is not uncommon to read a story about the trans experience.

There is still progress to be made

Despite these advancements, prejudices linger. Vietnam’s traditional family values remain deeply rooted in Confucianism, which puts the needs of family and society ahead of individual desires. Multi-generational households, with people conforming to prescribed gender roles and patriarchal views of man as head of the family, are still common.

In a country where families are considered to be the bedrock of society, for LGBTQ people shunned by their parents, wider social acceptance offers only some consolation.

Unsurprisingly, there is a generational gap, with the elderly most likely to resist change. One doctor recounted the tale of a 16-year-old that was assigned female at birth, though they identified as male. While the parents were understanding, the grandmother was not, and a man was paid to “fix” the teen—a disturbing euphemism for “corrective rape.”

While the country’s recent pro-LGBTQ actions have been welcomed as a step in the right direction, they fall short of providing a legal regulatory framework enabling implementation. With regards to trans people, a transparent and accessible procedure for changing one’s legal gender is still outstanding and hormone therapy and gender reassignment surgeries remain unregulated. While same-sex unions are no longer banned, they are also not legally recognized.

A draft law protecting the legal status and rights of trans people was due to be reviewed by the National Assembly this year. But several setbacks at the Ministry of Health, the department tasked with presenting the new law, have stalled progress. November 2019 saw the retirement of then-Minister of Health Dr. Nguyen Thi Kim Tien. With the arrival of a Covid-19 outbreak, these amendments have fallen down the national agenda.

The legislative delay is further compounded by next year’s May elections. Voters will choose deputies to represent their interests at the National Assembly and People’s Councils for the 2021-2026 tenure, as part of Vietnam’s one-party system.

Psychological consultant and relationship expert Mia Nguyen regularly writes about gender, relationships and sexual behavior in her weekly Love, Marriage and Family column in the Phu Nu TPHCM (Ho Chi Minh City Women) newspaper. Nguyen, who was assigned male at birth, has been engaged to her Australian fiancé, Austin Rennie, since 2017. She longs for the day they can marry and enjoy the same rights and protections as other married couples.

As it stands, if something were to happen to one of them, the other would have no legal claim over any property—much less over Mia’s adopted daughter. With Nguyen’s female identity not officially recognized by the state, she was legally obligated to sign papers as the child’s “father,” while Rennie has no official role.

“Legally recognized unions open to everyone would promote family life and stability, without affecting marriage,” she told VICE News.

In a 2014 survey of over 5,000 people, nearly 53% said they did not want same-sex marriage to be legalized, while just 33% supported it.

“The calculation is that Vietnamese society is not yet ready for same-sex marriage,” Nguyen said.

According to Nguyen, there is an obvious alternative. “If we really want to protect all couples and families, irrespective of gender and sexuality, then we should at least support civil partnerships.”

“Now that would be progress.”