In 2009, the Los Angeles Conservancy and its Modern Committee examined LA’s unique religious heritage with a one-day tour of five spiritual institutions. The self-driving sojourn was called City of the Seekers: LA’s Unique Spiritual Legacy, and it brought much-needed attention to Southern California’s role in the founding of 20th-century fringe religious institutions. It also helped shed light on the way spiritual freedom in Southern California has enabled artists to make visionary work as part of their creative practice.

Inspired by the Los Angeles Conservancy’s project and a spiritual-themed bus adventure from LA’s own offbeat tour company, Esotouric, “City of the Seekers” is a column about how Southern California has enabled creative people to make art as an expression of their spiritual practices.

Videos by VICE

Saitic Isis by J. Augustus Knapp, 1926 (WikiCommons)

In 1928, mystic, lecturer, and occult book-collector Manly P. Hall published The Secret Teachings of All Ages, a dazzling encyclopedic compendium of ancient texts, esoteric traditions, and musings on metaphysics that became an instant bestseller, in part because of the incredibly detailed and visually striking illustrations by J. Augustus Knapp. Due to the book’s success, Canada-born Hall moved to LA and opened the Philosophical Research Society in the 30s. It has become one of the stops on the “City of the Seekers” tour. Illustrator Knapp also relocated from his home in Kentucky to continue making art in LA, creating a tarot deck with Hall in the meantime. Through the artful marriage of images and words, the seeds for the derided but nevertheless important New Age movement was planted in Southern California.

Secret Teachings of All Ages by Manly P. Hall; illustrated by J. Augustus Knapp (via WikiCommons)

After Hall made his way out West in the 30s, many other broad-minded people did, too. Most of them settled north, as LA was still just known as a frenzied free-for-all feeding off the nascent film industry. Nonetheless, captivating orators such as Charles Webster Leadbeater and Annie Besant—theosophists who espoused groundbreaking notions such as women’s rights—established centers in Hollywood and inspired the likes of Aldous Huxley.

Like Hall, Huxley moved to LA in the 30s and fell in love with the freedom that the rapidly developing area offered. Mirroring Hall’s DIY approach to crafting his own credo, Huxley set out to find his own brave new world in the City of Angels, quoting a line from the late-18th century artist and writer William Blake’s “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” in his slim volume, The Doors of Perception, published in 1954. The book describes Huxley’s experience with mescaline, which would in turn inspire the name of the band, The Doors.

Huxley Over William Blake’s Urizen Praying, by Tanja M. Laden (originals via WikiCommons)

At the same time, between 1941-1960, Huxley penned over a dozen pieces for a periodical published by the Vedanta Society of Southern California. Vedanta is the most visible of the six original branches of Hindu philosophy, and in turn has spawned several of its own offshoots. In the Golden State, it was Advaita Vedanta, as interpreted by Indian mystic and yogi Ramakrishna, that flourished. Ramakrishna’s yoga-infused philosophies continue to define the Vedanta way of life in Southern California, where there are five spiritual centers, and is part of the reason there are so many yoga studios in the Western world today.

Left to right: Vedanta Swamis Ramakrishna, (1836 – 1886); Sarada Devi (1853 – 1920); Vivekananda (1863 – 1902) and Brahmananda (1863 – 1922) (all via WikiCommons)

In the great succession of swamis, it was Prabhavananda who inspired author Christopher Isherwood, philosopher Gerald Heard, and Huxley. Today, the art of portrait photography and painting remain very important to the Vedanta Society. Take, for example, Swami Tadatmananda—born in 1932 in Detroit, Michigan as John Markovich—who joined the Vedanta Society of Southern California in 1959. Until his passing in 2008, he painted portraits and landscapes in a material representation of his religion, carrying on in the tradition of Blake, Knapp, Huxley, and The Doors.

In Los Angeles, visionary/visual art had officially taken root, but its original purpose was not to hang on the walls of patrons. For much of the first part of the century in LA, art was generally not made to be exhibited, but rather it was created as part of one’s spiritual expression through creativity and vice versa, as well as a way to relay information and illustrate arcane texts and sacred images such as the ones at Manly P. Hall’s Philosophical Research Library.

The Art of Ann Ree Colton and Jonathan Murro, courtesy of the Ann Ree Colton Foundation of Niscience, Inc.

Another stop on the “City of the Seekers” tour was a campus in the bucolic LA suburb of Glendale, where Ann Ree Colton (1898-1984) established the spiritual foundation of Niscience, based on a word she herself coined, which means “knowing.” Inspired by its namesake’s early gifts as a dream analyst, clairvoyant, and healer, the Ann Ree Colton Foundation of Niscience, Inc. takes a highly non-traditional approach to Christian teachings that likely wouldn’t fly anywhere else in the country but Glendale, yet it’s still going strong. Not surprisingly, for Niscience co-founder Jonathan Murro (1927-1991), creating art was a very important aspect of the faith, which also incorporated philosophy and science.

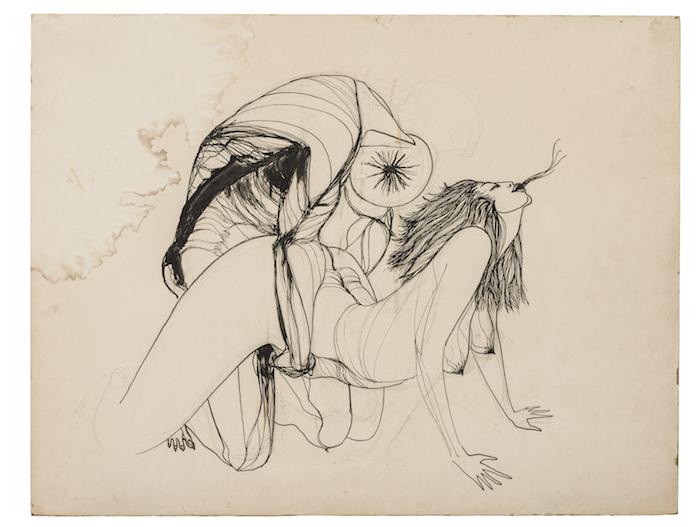

Meanwhile, preeminent 20th century occult artist Marjorie Cameron (1922-1995) opened her own doors of perception through peyote and her associations with another fascinating LA occult figure, Jack Parsons. She had also been attending the aforementioned lectures by Leadbeater, Heard, and Huxley, which she said in interviews influenced her work. But in a 80s interview with art historian Sandra Leonard Starr, Cameron discussed how LA didn’t have much in the way of a visual arts scene in the 40s, despite a flourishing contemporaneous appreciation of jazz, followed by poetry in the 50s. (And, of course, a film industry.) But visual arts, at least in terms of galleries, were a tough sell in LA. Cameron felt its effects firsthand: her drawing, Peyote Vision, shut down the famous Ferus Gallery on its opening night in 1957. It’s now clear that Cameron was among the first to really say it was OK make art for art’s sake in LA, all while staying true to your own personal philosophy.

Peyote Vision (1955) by Cameron, courtesy of the Cameron Parsons Foundation, Santa Monica

Since Cameron, there has been a steady supply of spiritually-inclined Angelenos who are either natives or have come to LA to work as a visionary artist, from designing album covers and rock posters, to making experimental films, to painting in their own backyard while taking mind-expanding drugs to make their visions “real.”

Through the visual arts, this column will examine the tangled threads connecting spirituality and creativity in Los Angeles, which has always enticed magnetic, charismatic leaders and lost souls alike—luring both seers and seekers to its legendary climate of freedom and promises of ultimate enlightenment.

Stay tuned.

Related:

Kaleidoscopic Collages Reveal Real Magical Visions

Painted Bodies and Canvases Elevate the Art of Magic

A Bespoke Occult Glyph for Every Quandry