“On this piece is an artwork of Mark ‘Mudman’ Modderman capturing Pig Ler with obviously excessive force.” Obviously. I hung on the editorializing. I was reading the description of a sculpture that one of my settlement’s colonists had made. “Pig is injured and seems to be in pain. There is a badger near the edge of the image, while the work suggests the concept of seclusion. This portrayal tells the story of the capturing of Pig on 6th of winter, 5499.”

When I first read these words, I was startled. I remembered that fight. Apparently, so did RimWorld, the space colony management simulator.

Videos by VICE

I’m used to being forgotten. If you play games, you probably are too. It’s one of those compromises that’s built into the foundations of so many digital worlds: I can experience this fiction, but I can’t impact it. It unfolds as it was programmed to and I’m tugged along after it like a cart behind a horse. Sometimes games will try to obscure this inflexibility behind smoke or mirrors. Characters will speak my name or pretend to have heard of something that I’ve done. They’ll call me the “hero of Kvatch,” or loudly thank me as I jostle by them in the street. If the world never really changes, these games can at least pretend that they remember me.

But over the past few years, games like Dwarf Fortress, Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor, RimWorld, and Darkest Dungeon have been finding novel ways to more substantially integrate players into their worlds. They write histories about the time that I spend in their worlds, and as these games do remember me, the compromise that I’ve become so accustomed to begins to fray. Shadow of Mordor‘s upcoming sequel— Shadow of War—promises in its tag line that “Nothing Will Be Forgotten;” it’s such a testament to this recent crop of games that I almost believe it.

These games are frequently celebrated for their complexity and depth, and for how lively their worlds feel. But in celebrations of these reactive histories, large questions tend to be elided: How does the game decide what’s worth recording as history and what isn’t? And what happens to players when their memories are at odds with the game’s?

Shadow of Mordor has been a touchstone in conversations about storytelling in games since its 2014 release. In it, the player controls Talion, a human ranger who loses everything and responds by killing many Orcs. But while its use of procedural storytelling is flashy, it is also incredibly limited.

The game’s twist is its Nemesis system. Mordor is controlled by Orc captains and warchiefs who also have memories which develop over the course of gameplay: If Talion kills a warchief with an arrow, he might pop up later in the game with a plate over his eye and an immunity to ranged attacks. When Ugakuga Sawbones returned from the dead with a scar and a shouted challenge, I felt—as advertised—surprised, and a little panicked.

In this, the Nemesis system is a success. Its world of indistinguishable mudpits becomes much more intricate and engaging in the presence of simulated rivalries, resentments, obsessions, and affections.

What I do with my sword is remembered; what I do with my time is not.

But once I’d put a little time into the game, I was increasingly aware of how selective the Nemesis system’s memory was. Shdow of Mordor’s seams started to split open as the system’s limitations became clearer.

There are certain events that warchiefs are coded to remember and respond to: routs, deaths, betrayals, beasts, and fires, to name a few—single, isolated events that take place during combat. But this net failed to capture or even acknowledge so many of the moments that I cared most about: My slow, patient pursuit of a particular warchief, looking for the best time to strike. My exploration of the game’s depiction of Mordor, piecing together the relationship between the warchiefs’ hierarchy and Mordor’s spaces.

And gradually, this feedback from the game—its decisions about what was worth remembering—began to seep into and determine my own experience of the game. As I came to understand which of my actions would be ignored, the pleasure drained out of the ways I’d made fun for myself outside of killing Orcs.

I became achingly aware that I was the only person in this world with a memory, despite the game’s constant insistence that it could recall our past. It didn’t feel like collaboration, it felt like a trick that I wouldn’t quite fall for—and the more apparent this became, the less substantial its world felt.

These are familiar trends in games that try to give their players a lasting place in their worlds. A complicated friction results, asking players to selectively toggle their own suspension of disbelief—to invest their time and care into the collaborative storytelling that the game promises, while turning a blind eye toward the places where these stories fall apart. This friction makes it difficult to put faith in a game’s world.

But as this faith is lost, something else steps in to take its place. The player is able to better see the series of cogs and gears moving in rhythm to animate another world. It becomes possible to understand how the game is writing its history and the decisions it’s making about how to communicate the player’s actions as a series of stories. And while being exposed to this picking and choosing might damage a fictive world’s plausibility, it can also be an occasion to reflect on where stories come from, and how we might fit into them.

Mordor depicts some of the dangers of this exposure: In a world that only acknowledges the player’s violence, a nonviolent player will be alienated and ignored. The game willfully editorializes the player’s action, implicitly judging which events are notable enough to be worth recording and which are insignificant according to the developers’ invisible yardstick. These value judgments permeate the game’s world and the experience of playing in it. Is it possible to remember players without these in-built evaluations of what comprises an “event”? Or is any game that historicizes the player’s actions necessarily going to trap that player in a rigid definition of history?

These questions take tidy shapes in Shadows of Mordor, in part because the line between the remembered and the forgotten is drawn so clearly. What I do with my sword is remembered; what I do with my time is not. Other games, like Darkest Dungeon, make these questions a little harder to look at head on. They hide their standards for stories, and blur the line between the imagined and the actual.

Questions of reality and fantasy lie at the heart of Darkest Dungeon. In this Lovecraftian roguelike, hired heroes explore dungeons, battle enemies, and become stronger—until their bodies or minds are pushed too far by the otherworldly horrors they face. Darkest Dungeon encourages players to treat their heroes with an unusual, complicated blend of care and exploitation. You need them, but you also need to use them.

Darkest Dungeon make its heroes unique by giving them positive and negative traits, called “Quirks.” There are multiple ways to acquire Quirks—most of them fairly random—but only one that feels narratively substantial: When exploring dungeons, heroes come across “Curios.” These are stationary objects which can be used or bypassed. If a player commands a hero to use that Curio, that hero might get gold, or information, or a disease. He can also get a negative Quirk, and sometimes that Quirk is very directly linked to the Curio. He is rattled by a Sarcophagus and develops Claustrophobia, or is distressed by a Beast Carcass and becomes Zoophobic. A moment of perturbation provokes a lasting terror.

The game itself doesn’t treat Quirks differently based on whether a player caused them. The Claustrophobia that one hero develops from being trapped in an Iron Maiden is identical to that which another hero spawns out of thin air at the end of a dungeon dive. All the same, Quirks that come from Curios are hooked into decisions that I made. I could have bypassed the Curio, but I made a call. I chose which hero would chance it. When I walk past the next Iron Maiden without investigating it, I’m referencing that decision. And when my hero’s Claustrophobia acts up during a tense battle in a narrow hallway, and he suffers a mental break, a subtle shift of momentum signaling the moment when I no longer have the upper hand—my distraught hero is referencing that decision too.

This is just a small part of the game. The main action of Darkest Dungeon concerns raiding dungeons, killing monsters, and getting treasure. Its setting and atmosphere are relentlessly troubling, haunted by aberrant forms and oppressive backdrops. Yet when I think back to the stories that I experienced in Darkest Dungeon, they don’t center around these overarching elements. They center around Quirks, these small points in the constitution of a hero where my intentions met with that of the game.

In this, the small scale of the Quirks system is its strength. Mordor‘s Nemesis system was defined and limited by its ambition. It demanded the player’s attention with a cymbal crash, and as a result its constraints and redundancies were all the more glaring. Quirks, on the other hand, are quiet—a subtle, slippery feature of Darkest Dungeon that is considerably harder to excise from the context it appears in. As a result, it lends depth to the other, more traditional elements of the game, complementing them by tying the player’s decisions to the game’s world.

When the Nemesis system succeeds, it does so at the expense of everything in Shadow of Mordor that falls outside its purview; when the Quirk system succeeds, its strengths dignify the struggle of the game’s heroes, the horrors of its dungeons, and the thrill of succeeding or failing.

Yet for all this nuance, Darkest Dungeon‘s memories are still fairly deterministic: The Quirks are hard-coded, as are their causes. Most games work this way—but there are some that seem to promise organic, novel stories, custom-tailored for each player.

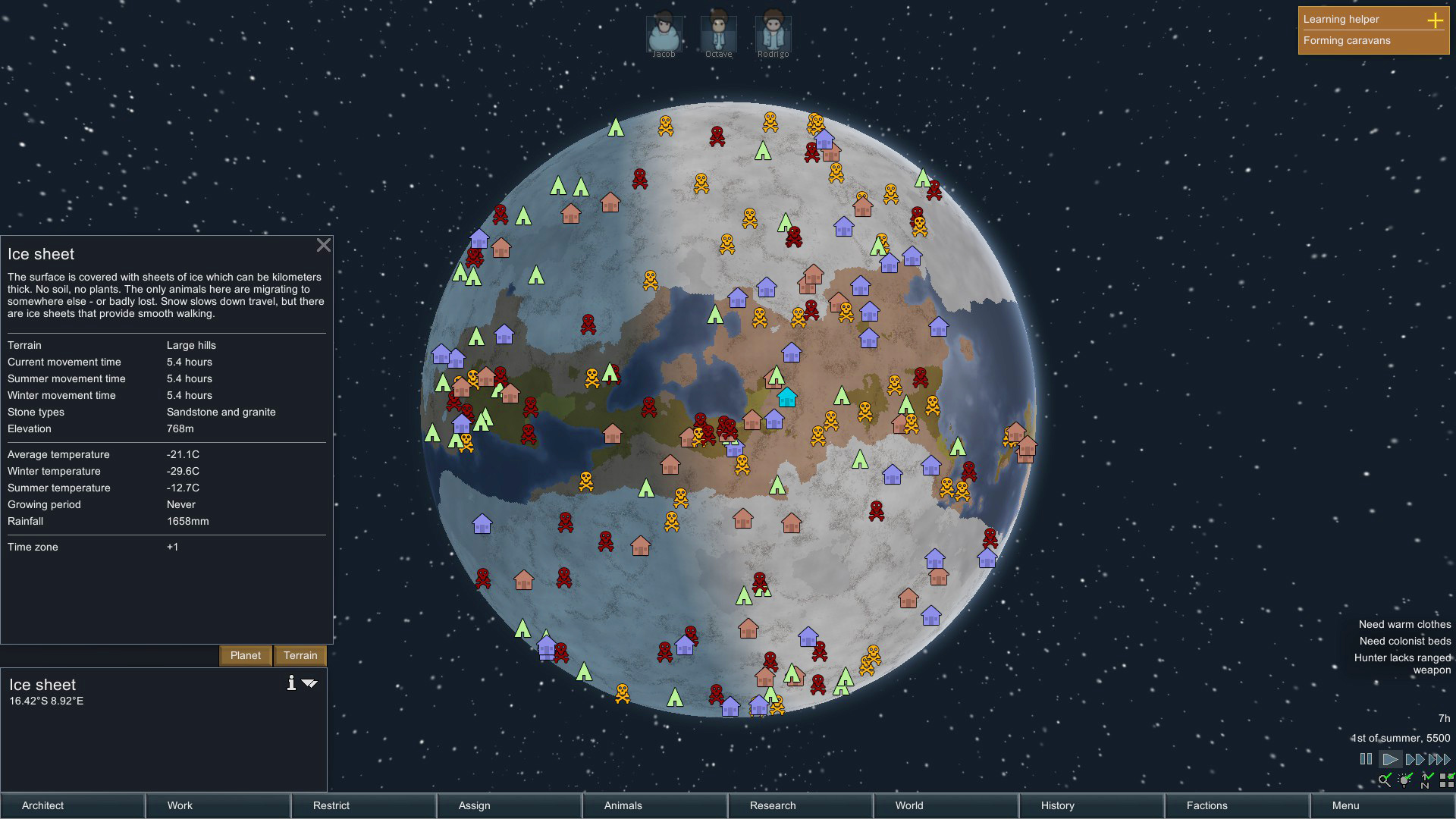

At the end of last summer, a few friends and I got very into RimWorld. One of us picked it up, then another, then two more. It naturally encourages this kind of viral spread: It’s really fun to talk about. Its depictions of space colonists (“pawns”) trying to eke a life out for themselves on a hostile planet—beset upon by invasions, plagued by extreme weather, and torn apart by their own procedurally-generated psyches—make for compelling micro-narratives ready for the telling. Specifically, I remember the stories that others told me about their RimWorld, and the stories that RimWorld told me about my own.

Rimworld screenshot courtesy Ludeon Studios

Among RimWorld’s many craftable objects are sculptures. Bad sculptors make trash; good sculptors make beautiful works that pawns like to be around. In addition to boosting the moods of pawns, these sculptures depict events in the colony’s history. Build enough sculptures, and you might have a complete history on your hands.

“On this piece is an artwork of Mark ‘Mudman’ Modderman capturing Pig Ler with obviously excessive force. Pig is injured and seems to be in pain. There is a badger near the edge of the image, while the work suggests the concept of seclusion. This portrayal tells the story of the capturing of Pig on 6th of winter, 5499.”

One of my settlers had made a sculpture, and this was the description. When I first read it, I was startled. I remembered that fight.I also remembered my thoughts during that fight. My colony needed people. If I nursed Pig Ler back to health, he could join us. On the other hand, this would require first aid, food, and space. Resources were at a premium, but Pig Ler represented a potential profit. He wasn’t a person, he was a bundle of pros and cons. We eventually convinced Pig Ler to join our colony. Mudman died of the flu a month later.

But it wasn’t until one of my colonists made this sculpture long after these events that I actually recalled the fight, and in so doing began to think of it differently. At the time, it had been merely one decision tree among many others. The sculpture reframed it as an actual event in both the context of the game’s fiction and in my experience of the game. That was the moment when Pig Ler had come aboard; it was also the moment when I’d made a decision that had used our food and first aid, and possibly inadvertently caused Mudman’s death. It felt like coming to the top of a mountain, turning, and finally seeing the forest instead of just decision trees.

RimWorld makes no attempt to actually understand its stories: They don’t have any mechanical effect on the sculptures they appear on, and the clumsy sentences that they’re written in bear clear evidence of the programming that handles their transformations from events into text. Yet even this slight, sidelong aspect of the game represented a new way of historicizing what I made my pawns do.

The more of these sculptures I read, the more my time with the game cohered into a continuous narrative bearing the mark of individual choices I’d made. It was a story that I was invited to look back on, something that I’d experienced but could still be surprised by. And after my pawns had made a few of these sculptures, they’d begun to affect how I looked forward, too. My experience of RimWorld became suffused with possibility: I felt that I was free to play the game in the way that felt most natural to me, and that the game would dutifully record my time with the game, no matter how I spent it.

What shattered those feelings of freedom and potential was Claudia Lo’s piece on RimWorld from the end of last year. Lo was curious about the game’s portrayal of romantic relationships, so she went through the game’s source code and discovered some peculiarities in how it handled gender and sexuality. To name a few: RimWorld had no completely straight women, that women were overwhelmingly less likely to start romantic relationships, that there were no bisexual men, that individuals with disabilities were universally less attractive, and that physical beauty was solely responsible for determining attractiveness.

No matter how inclusive or attentive a game might be in recording the player’s actions, the player themself is necessarily limited to what the game’s world allows for. And this, too, is subject to editorialization. In building these digital worlds rife with possibility, the developers are necessarily making decisions about the horizon of the possible and what rules run these worlds. Whether this limitation is apparent (as in Mordor) or concealed (as in RimWorld), these constraints are always present—the games that seem to have lifted them have only naturalized them, rendering them invisible through a “preemptive and violent circumscription of reality” (as Judith Butler writes in Gender Trouble).

RimWorld‘s sexual politics are a particularly brazen example of this, but, in truth, this circumscription is at the heart of any game that tries to simulate reality’s messy complexity. Making a sim requires making decisions about what systems are necessary for players to feel like the game is a sophisticated and responsive system that rigorously models the real world, and what systems can be left out without damaging the fabric of the fiction.

These judgments about inclusion or exclusion are frequently going to seem intuitive to us, the players—that’s the point. Of course RimWorld has a detailed system for appetite and satiation; survival games always have starvation mechanics. Of course it doesn’t claim to accurately model the ways people fall in love; they’re ambiguous, and confusing, and not very relevant to building a space colony anyway. But even when these choices make sense to us, when they seem organic or natural, they are still choices. They are still the product of a person deciding what matters and what does not. There’s no such thing as a history without these decisions—there’s no history that isn’t an expression of belief.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Screenshot: WhisperGames -

Screenshot: TrampolineTales -