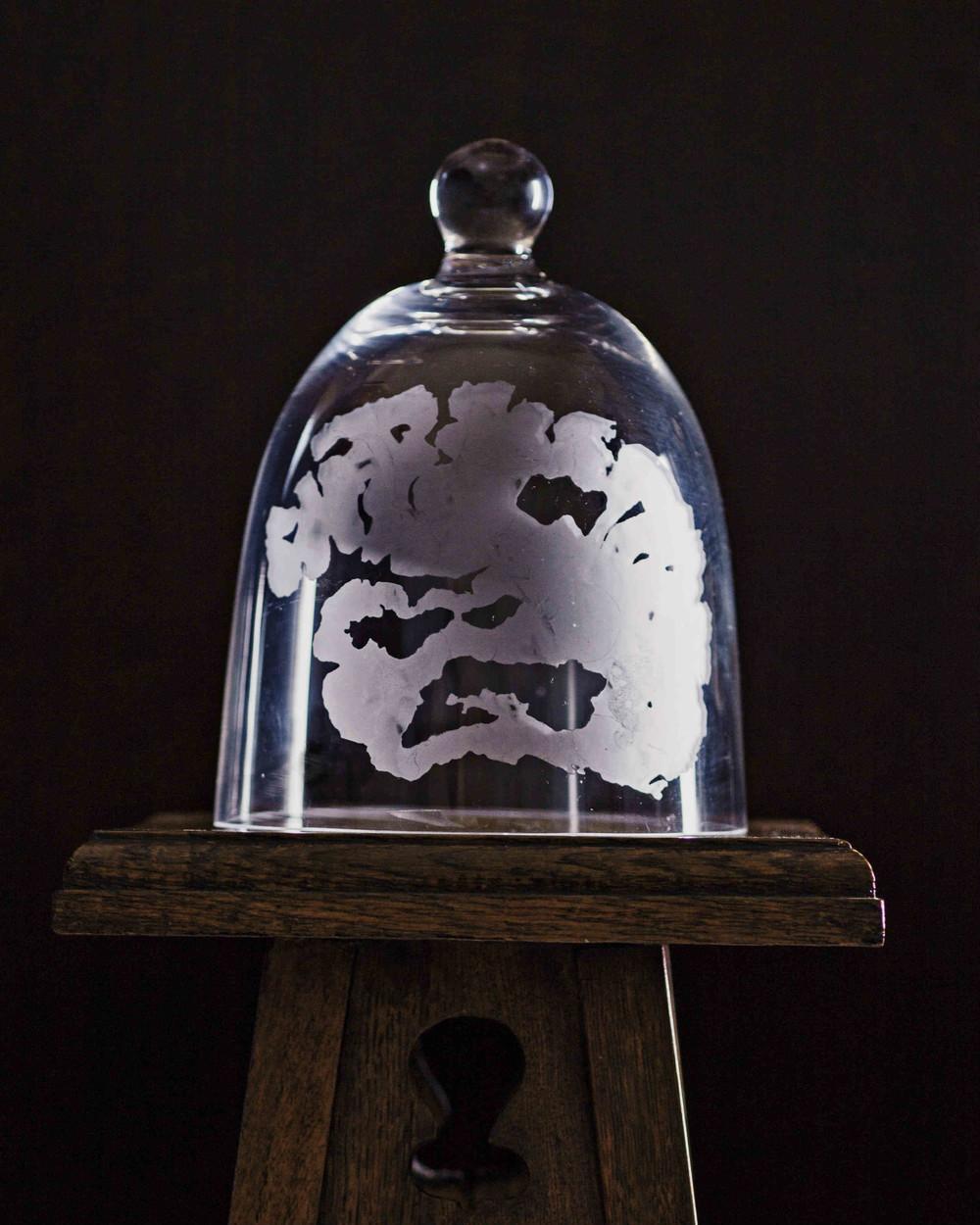

‘Charcot’ by Kirsty Stevens. MRI scan etched onto a bell jar

Multiple sclerosis, or MS, is increasingly common in the UK, with over 100,000 reported cases and a growth rate of 2.4 percent every year. Worldwide, there are reportedly 2.3 million sufferers—though most diagnosed are given a “wait and see” policy of no drug therapy, which can often lead to the disease getting worse or relapsing. In September of this year, a leading charity called this out. Earlier this month, the MS Trust published a report expressing the vital importance of expert support staff, which sits shakily alongside the continuing crisis within the NHS.

“The first relapse was by far the scariest one I’ve had to date,” says artist Kirsty Stevens. “I had optic neuritis in my left eye, which eventually caused me to lose sight in that eye for a short period, which was terrifying. My balance was off, I could barely walk in a straight line, which I tried to ignore at first and I remember being unbelievably tired and not really fully aware of what was going on. This all happened so quickly that, after an appointment with my GP and then an ophthalmologist, I was taken in to hospital. My time there was very hazy; I was in a kind of dream-like state of mind. Friends came to visit and I didn’t even recognize them.”

Videos by VICE

MS is a hidden disease—one that attacks the myelin coating of nerves around the spinal chord with unpredictable and damaging effect. Despite the diagnosis, it remains an enigma: symptoms shift undetected beneath the surface like water molecules held in an opaque balloon. No two people have the same experience and an individual’s symptoms can alter daily. It’s a world of uncertainty—one that can often be misunderstood by those who have no reference to understand it. In Earlier this month an Australian woman was abused for her condition.

With the threat of ignorance toward those suffering, artists like Hannah Laycock and Kirsty Stevens can make a real difference. Their work tackles the knowledge gap by creating art that is tangible and accessible. As MS sufferers, they have been using their craft to try and make the invisible visible. MS may be a difficult chameleon of a disease, but it is not the end: they’re “trying to make it a universal thing,” as Hannah says, to bring to life that “feeling of being consumed” and, ultimately, to find hope.

“I don’t think, hmm, this is what I feel from multiple sclerosis, so I’m going to try and turn that into an image,” says Hannah. “MS always changes. It never stays the same. I’m not trying to document. It’s impossible to do that with MS. I have to engage with what I’m feeling.”

A photo from Hannah Laycock’s ‘Awakenings’ series

Hannah’s work is visceral and immediate—her photos mix naturalism with artifice, the soft with the hard. There’s a feeling, looking at her work, of confusion and submersion—as if the entire world was being viewed from behind a diluted bottle of milk. One of Hannah’s photos is a portrait of her submerged in a bath.

“There’s a haziness to the water that I’m submerged in,” Hannah says. “It’s representing the cognitive issues you get and the memory problems. It’s a fogginess, a fatigue. Then there’s the intangible nature of the future: whether you’ve got MS or not, you don’t really know how your future is going to unfold. But MS adds another uncertainty; because you don’t know what journey your MS will take.”

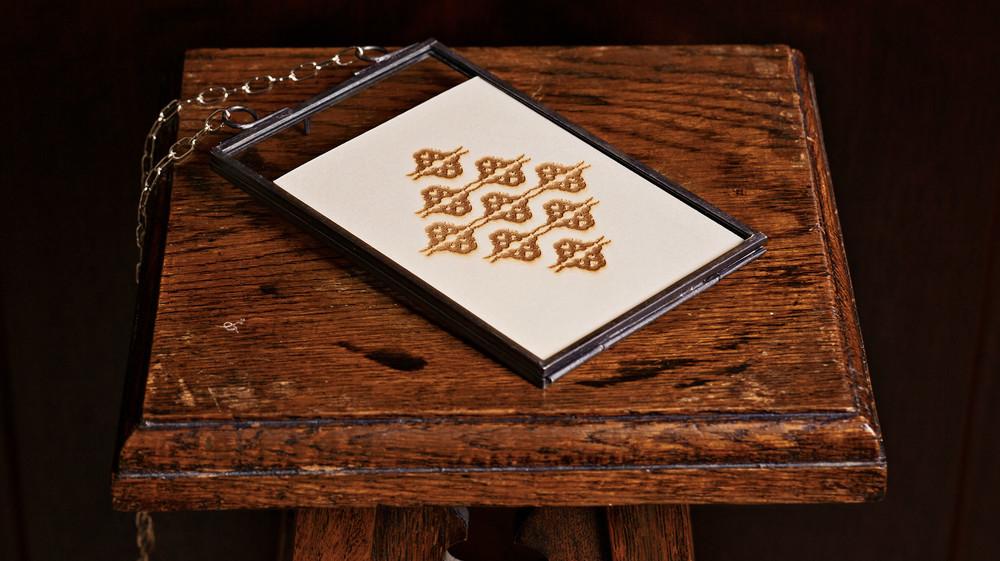

Stevens’s laser etched lesion print

One of the great misunderstandings of MS is that all those suffering from the disease are wheelchair bound or that, if they’re not, then their disease is somehow less difficult. “Sometimes it’s how people interact with you and react to you when you tell them you have MS,” says Hannah, “A lot of people say ‘Oh, but you look really well!’ and that’s very frustrating. Yeah, I probably do look well, but all the symptoms I’m actually dealing with you’re not going to see, because they’re all beneath the surface.”

Kirsty Stevens agrees. When she was diagnosed with MS in 2007, she was “devastated” and “somewhat embarrassed.” “One of the main fears and thoughts I had,” she explains, “was that I would instantly end up in a wheelchair. Looking back I realize how silly I had been and how uneducated I was about MS.”

Photo by Hannah Laycock

Kirsty’s work, Charcot, uses her brain scans for inspiration. She found “damaging lesion shapes” visible on her MRI scans, which she played about with to create intricate patterns. Named after Jean Martin Charcot, who discovered MS in 1868, her work aims to “bring the hidden effects of MS to people’s attention [and] to help empower those affected by MS.”

“People need to know what actually goes on inside the body and what that damage can result in,” Kirsty adds. “I have medication that I need to inject three times a week in order to slow down the degenerative effect of my condition and I am affected by fatigue and cognitive issues from time to time, but it’s also changed my life in a positive way. At first I was embarrassed and I would worry about the people I was telling because I didn’t want to make them feel awkward, but now I am proud to be part of the strong MS community. I really wanted to show people that such an adverse situation can have a positive outcome.”

Photo by Hannah Laycock

It’s obvious that Kirsty and Hannah have found a real purpose in their work. While their disease causes real uncertainty in their daily lives, the work that they create provides purity and focus.

“I kept telling myself: whatever happens you must finish your work,” says Hannah. “That it will all be worth it in the end. The image of the fabric covering my head illustrates suffocation. I feel that’s a universal theme. But it’s also a colorful image—there is hope and light at the end of the tunnel. I might be having a tough time, but there’s always an end, something else to look forward to that’s better.”

Follow David Whelan on Twitter.