Although three decades have passed, “the 90s” has maintained a firm grip on the collective consciousness. The revered decade has become shorthand for “cool”.

And maybe everything was cooler back then. It must have been, because the world refuses to relinquish 90s nostalgia.

Videos by VICE

Buried under the weight of memories from my own distinctly 2000s childhood are fuzzy glimpses of “typical 90s” signifiers, the kind where you’re not sure if the memory was real or magicked into consciousness from a photograph. Spice Girls on the radio. Tiny jelly sandals. A 1999 rave in a Footscray warehouse with mum, where my three-and-a-half year-old self wore glitter eyeshadow to match my sparkly halter top.

My parents were in their early 20s in the 90s – dad a photographer/bike courier and mum a fashion designer, who made rave wear under her WRONG label.

They were part of a wave of young creatives invigorated by the coming millennium and immersed in Melbourne’s growing fashion, art and music scene. But most importantly, the evolving party scene, too.

For those of us who weren’t there, or are too young to remember, the idea of “the 90s” has been imbibed in our consciousness through three decades of reverent media. It’s often America-centric: scenes from underground warehouse raves from New York, Chicago, LA. Elsewhere: London, Tokyo and Paris.

It was all happening out there. But Melbourne was also the birthplace of a distinct culture, the tendrils of which have stretched across three decades, weaving the fabric of community, innovation and creative dynamism that backgrounds the music scene to this day.

How did it start?

NASCENT PHASE

The 90s rave movement was global.

In the late 1980s, acid house washed out of the queer Chicago club scene and across the globe. It was a new, exciting sound that would inspire an entire generation. The evolving music genres coincided with the rise of new technology – and new designer drugs. It was the birth of a new culture. Tech, drugs and art propelled each other, intrinsically linked.

This music pushed people to gather outside of the clubs, in warehouses, where they could hear the new stuff they loved, find community, wear whatever they liked, pop a pill, and dance.

As referenced in Graham St John’s tome, FreeNRG: Notes from the dancefloor, “The utopic-transcendent rave arena is commonly understood to have been an escape from the heterosexualist, macho and aggressive predatory sexuality prevalent in rock, disco or nightclub settings.”

It was escape. It was community.

When the rave movement would finally reach Melbourne in 1989, it was imported, similarly to Sydney, by British immigrants.

Pioneers of the scene were Richard and Heidi John, who migrated to Melbourne that year.

“The party scene in London was alive,” Heidi told VICE. “It was kicking, it was pumping, but that wasn’t happening in Melbourne. What was happening was little clubs, which were fine, but not playing rave music. We weren’t interested in house, we weren’t involved with jazz. None of the house music was really that deep.”

Melbourne’s nightclubs were home to a thriving gay scene. They were ahead of the curve, Richard said, in terms of the music. But the Johns wanted to build something similar to what they’d been involved with in London. It happened organically.

“We’d see what we want to see, and we’d go for it,” Heidi said.

“We were strangers from another country,” Richard told VICE. “I was 35 years-old when we arrived, and so the people we were meeting were like 18, 20. We were older. And it was funny because it just happened. It was inevitable, it was a natural process, we didn’t have to go looking.”

“People came to us,” Heidi said. “It was the right moment, the right time.”

Richard and Heidi are accredited with throwing Melbourne’s first underground rave, Biology, along with Mark James, a prolific DJ and promoter, whose Pure parties, held at the back of the Palace Theatre, were some of the first to bring international rave DJs to the city.

If it took Australia a few years to catch up, it took Melbourne even longer. International acts, immigrants and backpackers would rarely stray down south of Sydney. Meanwhile, new music could take months to reach Australian shores.

“The music was really hard to get,” Mark told VICE. “I guess I was fortunate. I went on a trip to the UK, because I was always watching what was happening overseas. So I thought I’d go check it out, and I went over there and came back with tons of music. It was all this really, really new stuff that had just hit the UK market.”

But the clubs weren’t quite ready to hear it.

“It was a bit of a catch 22,” said Mark. “Because techno music wasn’t really very popular, but also not many people had heard it. I started playing it in the clubs and the owners and all that didn’t really like it.”

“In those days, you weren’t even allowed to wear trainers in clubs. I remember I’d come back from the UK with a pair of Pumas and the security’d say ‘you can’t come in’. I’d be like ‘I’m the DJ!’. But you couldn’t dress like that. So, it all sort of started from there, there was this anti-rave type thing throughout the clubs. I thought, well, you know, I’m gonna keep pursuing this. So I started my own night up. That was Pure.”

Andrew Till, a prolific DJ, producer and record label boss, had been playing in clubs for years before the raves began.

“The beginning of this was like the death of club culture,” he told VICE, “From the 80s to the 90s, Melbourne had the most nightclubs per capita in the world. But the rave culture didn’t generate any money because people weren’t drinking.”

Mark, Heidi and Richard threw Biology at a venue in Albert Park, in 1990.

“And that was great,” Richard said, “But that wasn’t what we were excited about. We were excited about warehouses. Different spaces. To transform an entire area.”

“And bring it alive,” Heidi chimed in.

“They were called dance parties in those days,” Mark said. “Not raves, though that terminology was starting to come from the UK. But it was like, ‘we’re putting on an underground dance party’.”

In 1991, Emmy Boudry immigrated from London to Australia, with her partner, Mark Hogan, a DJ. They were in their early 20s.

“We’d come from witnessing the birth of the rave scene in London in 1988 and 1989,” Emmy told VICE.

“We got to Melbourne and there was just this tiny little club scene developing with a few ravers, y’know? You’d go to a club, a kind of grungy club, and there’d be maybe 50 ravers. It was small, tiny.”

“We just thought, wow, this is a really fresh scene here. There’s not many people but there’s a lot of energy and enthusiasm to start something.”

Emmy and Mark formed a production crew, Right On One, and threw their first party just a few months after they arrived. It was called Quadrant, held at a communist warehouse in the CBD.

“It was on two levels. It was very underground,” Emmy told VICE.

Richie McNeill, or DJ Richie Rich, was one of the prolific scene DJs who played at Quadrant.

“There were communist flags hanging and the venue was illegally selling alcohol,” Richie told VICE.

“The cops came and shut it down and Mark was locked in the toilet. They were trying to pin him for organising it and for dealing drugs and he wasn’t, but he was locked in the toilet for half an hour and Emmy was banging on the door trying to get him out. I was dealing with the police with [fellow DJ] Ollie Olsen. They wanted to arrest us because we were playing this music.”

UNDERGROUND

The scene was small, and tight knit, Emmy described, with only five or six DJs playing at a rave.

“Depending on which production crew you were in, and there were only three or four of us, you had your little handful of DJs. And they would go from one production crew to the other. We would always make sure that we held our rave on a date that nobody else was organising a rave on.”

“All of a sudden, within a space of twelve months, these little things were popping up everywhere,” Richie told VICE. “Photocopied flyers, and the first Biology. It was like six or 700 people and we all thought, wow, this is massive. It was literally like 700 people and it felt like thousands because it was a real tight knit community.”

Richie, who later formed his own production company, Hardware Group – to this day responsible for some of Australia’s biggest events – said he played at about 20 of Emmy and Mark’s parties. He called the duo “unsung heroes of Melbourne”.

“I always looked forward to Emmy and Mark’s gigs because they were always in different venues. Mark just had this uncanny ability to find weird spaces. I remember playing Floatation on the Polly Woodside, and after that, one in a tunnel just underneath Flinders Street Station where the Banana Alley vaults are.”

“You held raves in warehouses where people lived,” Emmy said.

“We were living in Fitzroy at the time, and we would find out about a group of people living in a great warehouse. And we’d go in, maybe it was a friend of a friend who knew them, like, ‘hey, we want to put a rave on in here, we’ll give you $1,000. What do you reckon?’.”

Presale was rare at the time. Raves would be advertised on flyers placed in rave wear stores, including my mum’s on Chapel Street. Central Station Records – a key player in Melbourne’s music scene – was another hotspot, but word of mouth was strong enough. Flyers were plastered around town and in car windscreens.

“The flyers – you just hand drew them or did them up on a Mac and then photocopied them at the Student Union,” Emmy said. She recalled being arrested and sent to court for aggravated littering, after being caught flyering in a parking lot.

“The judge said to me, he was laughing because it was so ridiculous, ‘Was it a good party then?’ I went ‘Yes, your Honour, actually, it was’, and he chuckled. And then they gave me a $50 fine and a twelve month good behaviour bond. I had no priors, I was a sweet little 20-something English girl. Aggravated littering. It was ridiculous.”

In 1991, Richard and Heidi teamed up with Phil Woodman, a Melbourne DJ, to form M.U.D., Melbourne Underground Dance collective, a crew which became famous for their Every Picture Tells A Story warehouse rave series. For their first Every Picture, they joined with ALSO, one of Australia’s oldest gay rights charities, to run the party, a move which synergised the queer and rave scenes.

“We asked them if we could go back-to-back, because they already had a big following, and we had nothing, we didn’t know how it was going to go,” Richard said.

But the first Every Picture was a success.

M.U.D. would go on to throw raves throughout the 90s, each at a different warehouse. Their mission was to provide a unique experience, one that brought people together from across the city to unite art, design and music, and showcase the talent of Melbourne’s youth.

A CONVERGENCE OF THE ARTS

For Andrew, the movement was more than just “rave”.

“I don’t even like to use the terminology ‘rave scene’ because for me, the rave thing was more of a youth movement,” he said.

“It was a global movement. The rave movement was a whole thing of unity as well. We were very naive, innocent.”

“I feel it was the last musical movement that we’ve had. We had gone through the 70s rock, rock and roll, from those days, to punk rock to new wave, then acid house was the beginning of it. And when it went to the rave movement, I consider it the last mass movement.”

Australia had ushered in the new decade in the grip of a recession. Melbourne had always been a working class city. Unable to rely on the looks and attractions that so many other cities had, Melbourne’s draw was in its art, fashion, music and nightlife communities, a phenomenon which distinguishes it to this day.

In the cracks between the universities, warehouses and townhouses, small cultures flourished, and a do-it-yourself culture blossomed.

“It was a new, fresh frontier,” Andrew said.

“We were given a blank canvas to do what we wanted to do, really, from being a musician to being a party organiser to being a DJ to being anything. It was a really fresh and interesting time.”

Electronic music was slowly reaching more ears, and the subculture was becoming delineated through community radio, community television, and the street press.

“There were things that aren’t here anymore,” Richie told VICE.

“There was street press. Beat Magazine, and several magazines that you’d pick up at Central Station or the WRONG Shop or Custard or Renegade. There was a whole supporting culture behind this. You had record stores where you had DJs behind the counter that would educate people about what’s cool and hip and happening. So you had curation going that way.”

“And then you had independent radio like Triple R and PBS. So there was a culture that was supported not just by a community, but also by an industry that was behind it, that was a bit more tangible.”

Kate Bathgate’s radio show on 3RRR, Beat in the Street, was highly influential in showcasing rave music and promoting the raves themselves. She’d have notable guests from the scene on, and would frequently give away tickets to the raves.

“She was phenomenal, she really pushed the music,” Andrew said. “She would have anyone who was into electronic music, from the rave DJs to myself, and everyone who was a little bit different.”

“At that stage the scene was like, each DJ had their own style. There were people into Detroit music, people into heavy hard acid, people into banging techno, people into hardstyle.”

“There was a community behind it all. And there was a place for people to go listen to that, on the radio. She was a big thing. She helped a lot of DJs.”

“That was massive,” Richie said. “That really brought everything together and really took the whole culture from, y’know, 1000 people, 1500 people, 800 people, raves all over Melbourne to all of a sudden, 5000 people at Hardware and 4000 people at Every Picture. And it just grew and grew and grew from there.”

“Basically, Kate was probably one of the most influential people in Melbourne at the time, with that radio show.”

“Melbourne was just very open to anything in those days,” Mark told VICE.

“And the music was really good. It was all about the music, at the end of the day. What was coming out one week, we were pushing the week after, brand new. We were importing records and all that sort of stuff. The people just really latched on to it and Melbourne was always a big entertainment, nightclub, fun type of city… so one thing led to another.”

For the young creatives inspired by the rapid acceleration of digital technology, anything seemed possible.

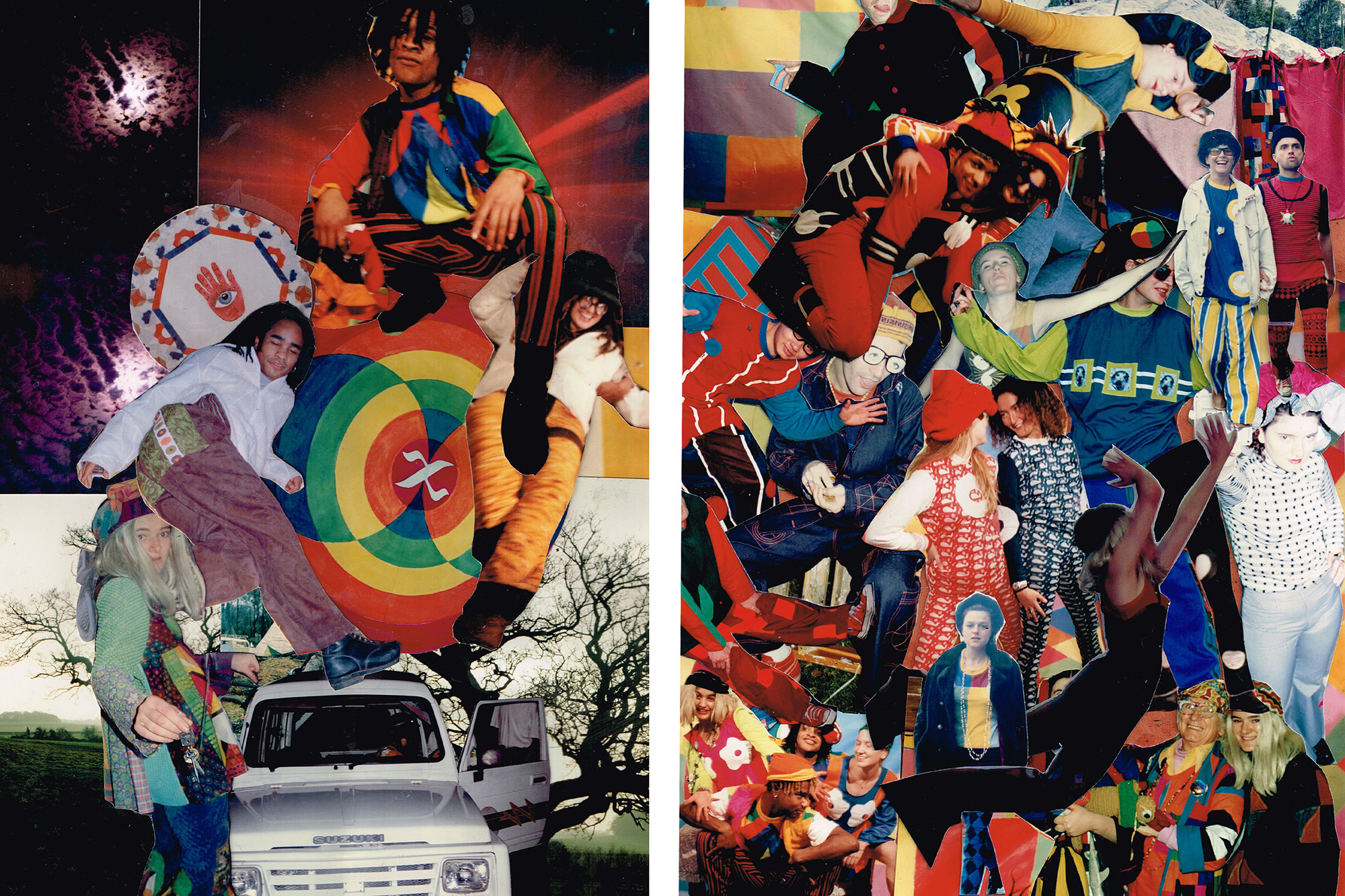

“Everything was bright, loud and colourful,” Andrew said.

“It was hopeful. And it was really positive, including the clothing. The clothing made a big part of it – it helped identify what part of the tribe you were from; that you listen to this music.”

“It was the beginning of computer culture as well. So we all got hooked into that, from people having their home studios to being able to produce music to artwork, digital animation to VJ-ing.”

Andrew described how, during 1991-92, VJs would do hours-long broadcasts on the community television station, Channel 31.

“They did things called Cyberthons, where they did 24-hour broadcasts, with computer graphics and DJs and interviews… It could never happen today. I can’t believe we got away with it,” he told VICE.

“No one knew what we were doing, it was all brand new. Especially with the new computer arts, we were very focused on that, a bit on the cutting edge. We were pushing the culture, pushing the art.”

The accelerating computer culture produced a momentous excitement about the future, later dubbed “y2k”. And the fascination with new advancements in technology, from virtual reality to digital animation, made its way into rave culture. As Emmy told VICE, rave organisers would touch on these themes in the visual and spatial design of their parties.

“We’d try to do different things. For Quadrant Two, I went to the Hoyts cinema where they were showing Nightmare on Elm Street in 3D. And I said, ‘Oh, have you got any 3D glasses?’ and they said ‘yeah, the movie’s finished!’ and they gave me hundreds of 3D glasses. Then I had a friend named Tao Weis who did all of these projections, and when you put on the glasses they were 3D. It was Quadrant Two in 3D. And this was in 1992.”

“Another time, in 1993, Virtual Reality machines were coming into play. Still very new. So we started getting a few of those into our raves, we’d have VR machines in the chill out room. We just tried to be a little bit left of centre. Something a little bit different.”

It wasn’t long before the defining trait of Melbourne’s underground raves had become their provision of an experience. They were full-scale productions, with crews striving to create environments that transcended the dancefloor. Alongside the speakers, lighting, and DJs would be performances, art installations and experimental venue design that embraced the innovative spirit coursing through the 90s.

After the first Every Picture Tells a Story, people would come to Richard and Heidi with ideas.

“People would come to us and say, ‘can I do something, can I do this?’,” Richard said. “And we’d say ‘we’d love for you to do that’. People came with their own ideas, for decorations, for performances, people wanting to create visuals. So we allowed all these people from different areas to come and do what they were best at.”

They acquired a lease at Global Village, a warehouse in suburban Footscray, where they held raves from 1993 to 1997. The M.U.D. raves would have various rooms, each decorated by different creatives who had approached Richard and Heidi with ideas. The raves served as a platform: a vehicle for creativity, connection and celebration.

“What we were trying to do as well was to create an environment where you didn’t have to take any drugs, or anything like that, to be stimulated and excited,” Richard said. “That was the whole idea of it.”

“What we were creating over here wasn’t even happening in London.”

For Amos, a partygoer who attended raves throughout the 90s, dressing up was the norm.

“It used to be all about dressing up and having fun. Anything colourful or furry. You’d even just make something yourself, throw together some bits of material. It didn’t have to be amazing. Just for fun, and to last for one night.”

To keep the cops and the neighbours from shutting it down, organisers resorted to crafty measures.

“We did Meaning of Life in 1993,” Emmy said. “We didn’t advertise it was at the Fun Factory, in South Yarra, which was a roller skating rink. We just had a 0055 number. Sometimes you’d put a 0055 number and people would have to call up to find out.”

“We went to Captain Snooze, and we just got vans full of mattresses. And I remember just plastering the windows of the Fun Factory with mattresses, to block out the sound.”

“There were no mobile phones, there was no social media, there was nothing, it was just a group of people. And there was so much love, so much energy, and life on that dance floor and everyone connecting and knowing that we’re all part of something special.”

As happens today, the cops would shut down raves purely on the basis of noise complaints.

“I would go to the local police station at about 8 o’clock at night, well before the rave had started, and had my sweet little English accent and I’d flutter my eyelashes,” Emmy said. “I’d say, ‘Oh, just letting you know that we’re having a 21st birthday party at such-and-such-address, and there’s going to be a few people, we hope it’s not too loud, but I just thought I’d come down and let you know.’”

“And they’d be really grateful, like ‘Ooooh, thank you for letting us know that. That’s okay’. And some old granny would complain and we’d get them knocking up at the door and saying to security, ‘Oh, can we speak to Emmy, please?’. And then I’d come and they’d be like, ‘Oh, Emmy, we’re really sorry. We’ve had a sound complaint’, and I’d be like ‘Oh no! So sorry, I’ll get them to turn it down’. Meanwhile I have a full on heaving rave going on behind me.”

THE HIGH PEAK BEFORE THE FALL

Melbourne’s warehouse rave movement was little more than a blip on the timeline. The community expanded and diversified. As the music became more popular, more promoters began importing DJs from overseas. The parties got bigger and bigger, and rave became a popular, more mainstream movement.

For Richard and Heidi, the commercialisation of the rave scene had made it about the money. It was no longer just for the love of the party.

“When it started to get commercial, when the music got more and more popular, every man and his dog wanted to be a DJ,” Richard said. “So where there were only six DJs in Melbourne, now you’d have 60. And there was nowhere for them to play, there were only so many venues, so they started holding parties to promote themselves.”

“Boom, boom, boom, big money, it became commercial, and it changed,” he said.

“Our parties were for the love of the party, they were complete and utter productions. The other parties were just DJs putting them on to promote themselves, and the latest technologies – anyone could have gone and hired them.”

As raves got bigger, it became harder to keep them under wraps.

Richie, whose Hardware parties down at Shed 14 on the docks attracted crowds in the thousands, said it wasn’t until the mid-90s that the clubs inevitably caught on to what was happening.

“It wasn’t until around 1993, maybe later, ‘94-‘95, when the Nightclub Owners’ Association got wind of it. All these big raves going down on a Saturday night for five, six thousand people. It was hurting their clubs, having an impact on their Saturday nights, so they all got up to rally the police for them to start clamping down on our events.”

“There was even a paper drawn up, a submission they made to the liquor commission. And it was like, we’ve got these clubs, we put all this money into our smoke alarms, and sprinkler systems etc. And these guys go into makeshift warehouses, and basically get a temporary licence and a temporary occupancy permit, and bring all these temporary toilets and stuff. And it’s costing them fuck all. And it’s costing us millions of dollars between our businesses, and we just don’t think it’s fair and you should clamp down on them,” he said.

“So all of a sudden, we started having the council come down, inspecting our events.”

Linked to the rave scene but something else completely was the outdoor party scene. Andrew described it as the “birth of a very special development” in electronic music culture.

“The other side where I got involved happened from ‘91, I consider it the birth of a very special development: the birth of the outdoor culture. The little parties and the raves. The first one happened on a friend’s farm for a birthday,” Andrew told VICE.

“Then another friend did one called Shiva Rati, which was probably the first proper outdoor party. We weren’t too much into warehouses. And we wanted to do outdoor parties. The sound was different. We were inspired by the music, and the music we played was predominantly for outside parties.”

By 1993, the bush raves had taken off. Earthcore was the first large-scale outdoor party, pioneering a culture that persists today. Heavily influenced by the outdoor trance raves happening in Goa, India at the time, the mid-90s became characterised by the doof scene.

As the music fractured, so did the community.

“The rave culture stayed up until ‘93, ‘94, before it fractured off into little subdivisions,” Andrew said. “People got to like certain styles of music, from drum and bass to jungle, or psytrance or Goa trance. Then there were the fractions of techno – Detroit techno, hard techno, Berlin techno.”

After 1995, the commercialisation of the rave scene was in full swing. Promoters were trying to one-up one another, raising the stakes, billing bigger acts, throwing increasingly larger parties. As raving became less underground, it became more profitable. The bush doof culture had been steadily erupting in Melbourne for years, with parties like Earthcore getting larger each year. It was the death of the underground, but the beginning of something else – a fracturing of the culture.

“In ‘95, trance kind of really started to take hold – psychedelic trance,” Emmy told VICE.

“And then drum and bass was one of the first genres that diversified out of the rave culture. You had rave and then you had drum and bass. And then you had trance. And then you had psy-trance and hard trance. You had different types of trance. And you also have the gay community as well, in the early 90s, which was quite big in itself.”

Hundreds of Australians went off to India to join the Goa trance parties in the mid-90s. Rave was transmogrified.

“By 1995 globally, people were saying techno was dead,” Australian artist and musician Gary Shepherd wrote in a 2007 blog post.

“A little over dramatic, but true in the sense that the old school generation had partied themselves out. The music was stagnating with safe (boring) tunes being played to cater for massive crowds as well as the new mainstream music TV/radio markets. So yes, to the old school underground, this era was over by 1995.”

By 1996, the queer rave scene had also become enormous. Amos described attending huge raves held at the Docklands, where the largest warehouse, Shed 14, was leased by the ALSO foundation.

“They used it for the big gay parties, Red Raw and Winterdaze.”

“[It] was a giant warehouse on a pier at the docks. You would go there and it would be full of a thousand ravers going off, it would take forever to try and get from one end of the dancefloor to the other,” he said.

“It was great because it was right next to the city but also kind of isolated from it. No neighbours. No noise worries. And cops were never around. You could rock up out the front and find people selling whatever you needed.”

“During the night you could sit along the sides of the pier over the water and enjoy some fresh air and smoke. In the morning when the sun was coming up over the city, they would slide open the side walls and the light would come in from the sunrise.”

POST-METAMORPHOSIS

Born out of a global movement and pioneered by a few young, inspired creatives willing to have a go, rave took hold in Melbourne. It left a legacy that persists today. If you look closely, or spend time in the right circles, you can still see the whispers of that energy, defined by a commitment to create spaces and places where people can come together in celebration, to find something new.

“The thing is that we all know how lucky we were to be around at that time,” Emmy said.

“And how special that time was, it was the birth of something. It was the beginning of a culture that’s continued on, that will never be the same because we were there right at the beginning. It was so new and exciting and fresh.”

“There were no mobile phones, there was no social media, there was nothing, it was just a group of people. And there was so much love, so much energy, and life on that dance floor and everyone connecting and knowing that we’re all part of something special. And it was very underground. And we knew how underground it was.”

“You were doing what you did,” Mark said. “In those days you didn’t sit back and go ‘oh, wow this is fantastic, this is great’. You’d just plod along, next one, next rave, get up on the ladder, get the deck back… it was just the job and the love of the music. You didn’t even really sit back and think about what you were creating in those days. It just happened. But looking back on it, we obviously did create something special.”

On what that era meant, Amos was resolute.

“Fun. Freedom,” he said.

“Melbourne was a party town. You could go out every night of the weekend and there’d be parties. Every night had so many great club nights, of all different styles.”

“You don’t have to be in a flashy, shiny venue that you’ve spent $4 million on with glowing bars and UV toilets and special carpets and tiles on the wall,” Richie said.

“The people just want cracking music, lasers, lights, good sound and a good time. And they’re happy to be in a dirty shed that drips dusty sweat from the roof – dust that’s been up there for 40 years – that lands in their eye and they have to get an eye flush because they’ve got pinkeye.”

“It’s funny, I drive around and see apartments and see offices and buildings and think: fuck, I remember playing a gig there, and I played under those wheat silos over in North Melbourne or DJ’d in that warehouse under there, to like 1000 people, and played in that place in Richmond where the Myer offices are…”

“There were all these great little locations and the police had no idea what was going on,” Richie said. “They had no idea.”

For Andrew, who still curates jungle, drum and bass and techno nights at Melbourne’s My Aeon, while so much has changed, there is still hope for the underground.

“Things did change in the 2000s,” he told VICE, “Rave culture moved on to lots of different facets. You hear it on the radio now. And there is no underground to a degree, with social media.”

“It’s been done, nothing is fresh.”

“But I’m waiting for it, I’m always waiting for it. I don’t know what, but I’d love to see what happens.”

Follow Arielle on Instagram and Twitter.

Read more from VICE Australia and subscribe to our weekly newsletter, This Week Online.