ABXY gallery was buzzing the day I met up with Zeehan Wazed for our interview. Other artists represented by the Lower East Side space—Vernon O’Meally, Grave Guzman, Corey Wash, Malik Roberts—breezed through sipping rosé and Coronas. Music played over speakers. ABXY founder Allison Barker’s dog grumbled at me for trying to steal a chair near his bed. The vibe was decidedly more lively than most Manhattan art galleries on a weekday afternoon.

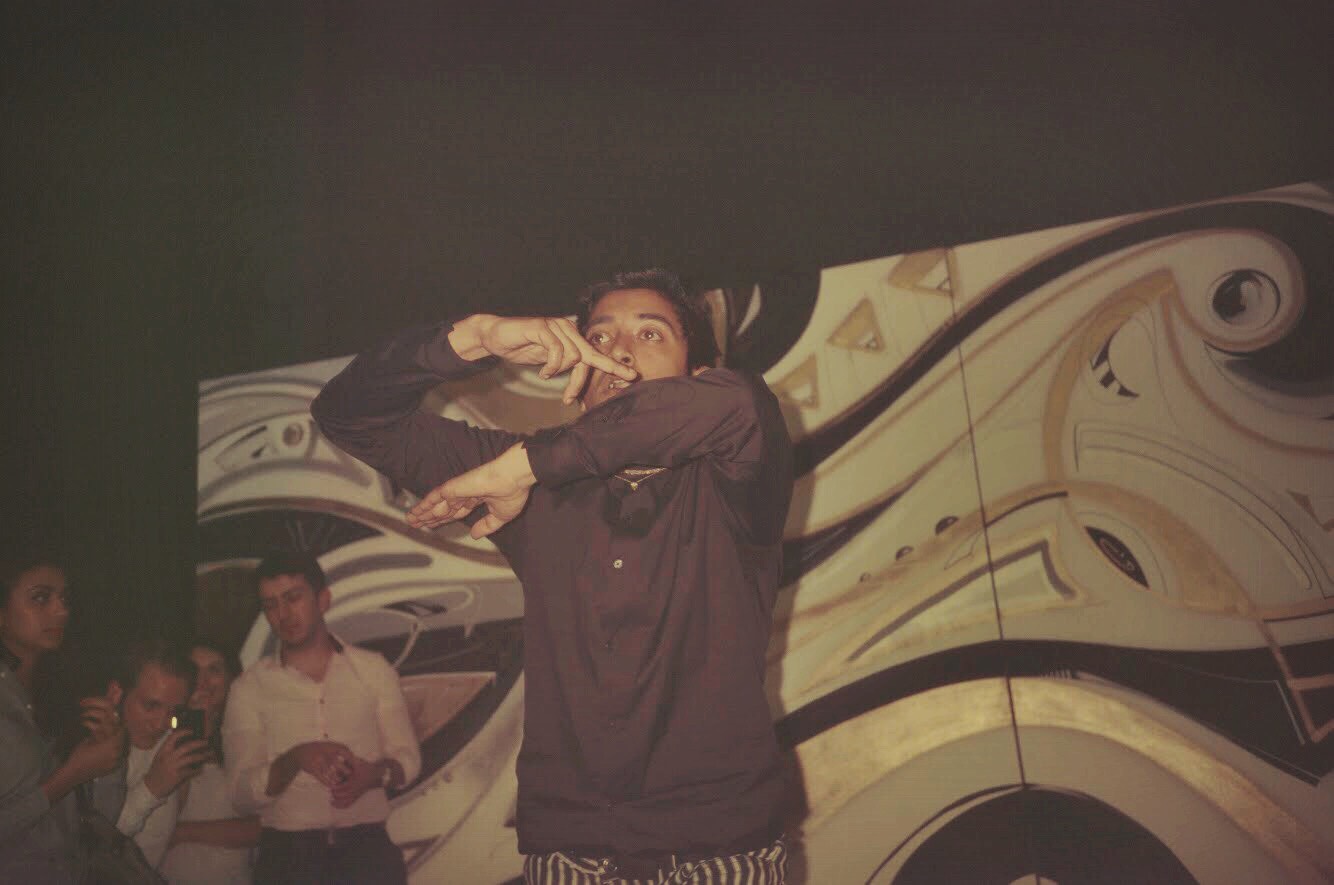

Wazed’s artwork, on view in the gallery until July 29, is dominated by street art-inspired black, gold, and white abstract paintings. They’re frenetic and mesmerizing, a little like the energetic young man who created them. After the artist and I settled into an alcove near a 3D-printed gold pendant suspended from a chain—also part of 26-year-old Wazed’s first solo show, Momentum—our conversation wandered, but with the freewheeling, excitable energy that seems to flow naturally at ABXY.

Videos by VICE

A few times, Wazed interrupted himself to apologize for rambling. “I’m all over the place. I’m the epitome of a millennial, in certain senses,” he said. “Some people might call it ADD or whatever, but I went off on many different tangents in my life, I guess.”

He really didn’t need to excuse himself. Wazed is clearly fueled by his free-ranging curiosity. His art is inspired by everything from perceptual psychology to hip-hop. He’s a dancer, painter, graffiti artist, 3D-sculptor, designer, and coder. And he’s entirely self-taught.

Wazed grew up in Jamaica, Queens, the son of immigrants, and thought life was supposed to be linear: you study hard, you get a degree in math or science, and you become a doctor or whatever. Documentation issues made it hard to apply for jobs, though, and as a teen, Wazed started dancing and entering art contests for cash.

“Taking the train over [to Manhattan] during high school, I saw people street performing, and I gravitated towards it, because I was this really quiet, Asian kid. I had a hard time talking to people, so I really liked dancing. It was a means of making money, too, because I couldn’t apply for things without a social security number,” he said.

“There was a sort of momentum to that: making money when I was young and having control over it. Being able to keep up with the other kids, or having the money to buy nicer shoes even, by doing something you love,” he added. “I kept doing it until I got, like, arrested a bunch of times. Just, you know, because they don’t want you performing on trains that much.”

The parks at Union Square and Washington Square became his dance studios. “I kind of want to tell every dancer to street perform for a minute, because you get so much reception from people,” Wazed told me. “If you can stop people at fucking Union Square, in the train station at rush hour? Then you’re doing something right.”

Around the same time, he got interested in graffiti. “I was gravitating towards hip-hop [culture], I guess,” he explained. “I was really fixated on graffiti and breakdancing, because with hip-hop, you get your own creative license. It originated from poor kids making up their own shit. […] I couldn’t afford dance classes, but I could at least enter a hip-hop contest with my own stuff.”

When it came time for college, Wazed ended up studying finance at Baruch College. “It was right next to the School of Visual Arts (SVA), which was such a tease,” he said. But he was mostly interested in dancing by then, competing a lot and making significant money. Eventually, he veered away from banking and “defaulted,” in his own words, to perceptual psychology. It wasn’t an art degree, but it impacted his art in ways he didn’t anticipate.

“I think about the body as a canvas, at least when I’m moving, and [I think about] where I allocate people’s attention. So [my movement] has this central configuration—this spiraling twist—to it, because i find a lot of power in this shape,” Wazed said. “That’s something I picked up from perceptual psychology: how you allocate attention and movement. And I really like to play with that in my art.”

Wazed planned his show, Momentum, meticulously. Swaths of similar vinyl shapes on the floor echo the paintings on the wall and draw the eye around a corner, where the delicate gold pendant hangs encased by a wooden frame. There’s also more to the show than meets the eye. When visitors hold up an iPad to four of the paintings, tiny silhouettes of Wazed dance amidst the spiraling lines.

“A lot of my dexterity in painting comes from dancing. The lines, muscle memory, and coordination converts onto canvas for me, like dancing with a can of spray paint,” he wrote in an artist’s statement. “That’s what I’m trying to show with the augmented reality component of this show.”

Beyond the connection between dance, graffiti, and technology, Wazed’s work is layered with deeper meaning, much of it stemming from his time performing on the streets of New York. “You start to notice the flow of people in the city,” he told me. “And that’s what also inspires my work. Not just dance movement, but the textures of movement in the city. I don’t think it’s just patterns, I think it’s also fate. I’m curious about how people’s feet have led them here, the trajectory of people’s lives, and I started to think about lines in that sense. How they intersect, and how people are meant to meet or even grow apart.”

“I thought my life was supposed to be a straight path, but I took off on many different tangents. All these things I’m doing, at some point I thought they were just completely arbitrary. And people were like, ‘Focus on one thing.’ But when you step back, you get to see how all those different tangents in life intersect to create a bigger, more beautiful picture.”

The machinations of fate also led Wazed to his place amongst the other ABXY artists. He met O’Meally in Union Square during his street performing days nearly a decade ago, and Wazed’s career blossomed from there. But while sharing a gallery and studio space with your best friends is dreamy, it’s not exactly the norm in New York’s largely white and privileged fine art scene. “People know we’re diverse, and I’ve been called an outsider artist, or even minority artist, and it’s pretty offensive, because I just see myself as an artist in general,” Wazed said.

He’s used to figuring things out for himself, and in a lot of ways Wazed thinks that’s more valuable than a fancy art degree. “I’m kind of glad I didn’t go to art school. Maybe this sounds full of myself, but I was never competing against my peers, you know? Just what I saw in books. And I knew I had to hold myself to those standards if I was ever going to make money doing art,” he said.

“I guess having a lack of resources made me become really resourceful,” Wazed added. “Honestly, once I did get my paperwork and my social security card, I was just so used to being independent and not working for anyone. I was able to do all this stuff for myself and do it within my own style.

“A lot of times you just have to push a little harder than everyone else does. That’s my momentum.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

More

From VICE

-

-

-

Buckshot on set of the "Hey" Music Video. Credit: Duck Down Music -

Screenshot: Marvel