Drug addicts seem to be the go-to subjects for raw-emotion-seeking photographers looking to try their hand at documentary photography. The problem is that most photo series featuring drug addicts shooting heroin into their eyeballs don’t offer insight into the psyches of the individuals being portrayed. Canadian photographer Tony Fouhse’s latest book, Live Through This, is different. Tony spent four years photographing addicts in downtown Ottawa. This book is a collection of intimate portraits depicting the struggle to get clean of one addict named Stephanie Macdonald. The photos challenge the conventions and ethics of photojournalism, while offering up a powerful portrayal of her addiction.

Tony met Stephanie while working on another photo series about drug addicts. He took pictures of her on various occasions, and eventually asked her if she needed help with anything. They worked out a deal—Stephanie wanted help getting into rehab and Tony wanted to take pictures of her. Tony’s intentions were never to act as a savior to the addicts he was photographing, but in Stephanie’s case he felt compelled to do something.

Videos by VICE

Over the course of six months, the two became extremely close and due to a series of events, Stephanie eventually moved in with Tony and his wife. As you would expect, a lot of chaos and struggle came out of their relationship.

Live Through This is a collaboration and conversation between Stephanie and Tony. His presence and their relationship is understood in the photographs, without being blatantly spelled out.

I called Tony at his home in Ottawa to discuss the nature of his work, his relationship with Stephanie, and the ethical dilemmas that surface when your connection to your subject gets out of hand.

VICE: You took pictures of addicts in Ottawa for a few years before meeting Stephanie. What was special about her that made you want to get involved?

Tony Fouhse: The thing about Stephanie that I thought was exceptional was her ability to get in touch with her emotions and show them to me. She kinda sparkles. It could also be that, I knew this was gonna be the last year I was going to be photographing down there and I wanted to actually make a mark on someone.

So, can you tell me about how Stephanie ended up moving in with you and your wife?

About five days before she was about to start rehab, she phoned me up and she felt like her brain was exploding. It was an emergency. They found an abscess in her brain and transferred her into the neurology ward. She was supposed to stay in the hospital for six weeks, but three days after her surgery she phoned me up and she said, “Come and get me. I wanna go home.” I said, “Where is home?” And she said, “Your house.”

What was it like to have a heroin addict living under your roof?

It was very difficult. Back in June, when I asked her if i could help her, I didn’t know that she was going to have brain surgery. Everything was kind of spinning out of control. After she got out of the hospital, she was like a child who was raised by wolves. She was really frenetic, happy to be out and happy to be alive. She was wondering what the future was gonna hold for her, but still falling back on her old habits. She was upstairs and trying to last as long as she could without waking me up and asking me to give her some money for dope. That lasted for about seven days. On the eighth day, she got up and she was a different person. It was like she had come through it all. She was way more aware. She had recovered from her brain surgery and she had mostly withdrawn from being a heroin fiend.

Did you ever think you’d get so close to her?

No, that was very surprising. I’m kind of a naive guy. I’m street smart; I can go to Los Angeles and photograph gangbangers and survive. But when it comes to certain things, I’m a very slow learner. Part of the way I like to work is that I don’t like to think about things too much. I just like to do stuff and let the chips fall. What certainly surprised me is the intensity of our relationship. There are so many things that happened that I didn’t photograph. A lot of the times when all this crazy shit was happening, I would just put my camera in my pocket and just deal with the drama. I had to decide whether I wanted to be her friend or a photographer.

Would you say you were more of a photographer or a friend to her?

At this point in time I’m more of a friend to her. When the project was happening, I had to make those decisions all the time. I had to question my morals and my ethics. She’s a smart girl and we had tons of conversations about that. I would say to her, “I don’t know what I’m doing. I don’t know if I’m helping you or hurting you.” Part of what a lot of my work is to go up to moral and ethical boundaries and explore how a person might react. In this case, I guess the person is me.

What was the hardest thing for you as a photographer, when that relationship started to evolve and you guys became closer as friends?

I think the hardest thing was being put into situations where I was given a tough choice. Here’s an example. Occasionally, I would go and pick up Stephanie in the morning and she’d be dope sick. She didn’t have any dope or any money and she’d say “lend me $30.” I had a choice, I could give her $30 and then we could get in the car and get some heroin or I could say no. If I said no, she wouldn’t not become a heroin addict. What she would do is she would go outside, stand on the corner until someone needed their dick sucked. She’d suck their dick, get the money, and then she’d go buy heroin. Those are the kind of morally fucked up situations that I would find myself in over and over again. I never did a project where the morals and the ethics were painting me into a corner in such an extreme way.

Aside from including Stephanie’s letters in the book, how did you involve her in the creative process?

What I decided to choose the pictures that showed her mostly isolated from her surroundings. Most of the context of her life was sort of gone. There are pictures of her taking dope and stuff like that, but mostly in the book, it’s what I would call portrait photography. Most of that, except when she was in the hospital, was shot in collaboration with Stephanie. We would be in a situation and I’d say, “Stand here, look this way, don’t look at me, don’t smile.” There was an artificiality to it. There’s an artificiality in all of my work because I don’t believe in objectivity. I think that if the photographer shows some of the means of creation, it is more honest.

Even though the pictures from the book are staged, you still get a true sense of loneliness.

I wanted the loneliness to come out, the isolation. Part of the reason why they’re staged but still look real is because the situations we were in were real. I was staging photographs in a very real, very charged, and very dramatic situation. The curator of the show that we put together said that the photographs are extraordinary and banal, just like the life of a drug addict. I wanted to encompass that also by eliminating all the context. I wanted to point to the fact that it was Stephanie and me in this together. My visibility in the photographs was meant to be understood rather than pointed out.

At the beginning of the book, you tell this story where you said to Stephanie that she should’ve died, because it would have been a better ending. What did you mean by that?

It’s like Stephanie and I had been to war together and at that point, we were both stripped emotionally bare and had nothing to hide. Plus, there’s a kind of black humor you need to apply when you’re in that kind of situation. It was all life and death. But when you’re in the life and death situation, one of the ways you survive is by making fun of it. Again, there are a lot of reasons why that’s in the book. It also points to my philosophy. I don’t believe in happy endings. In the end, I’m still not sure if this is a happy ending or not because Stephanie is still struggling. She’s alive and 100 times better than when I first met her, but every day for her is a struggle. Yes it was a happy ending, but it was only as happy as any of us can expect. We survive to fight another day. What could be happier than that?

Follow Stephanie (the writer, not Tony’s subject) on Twitter: @smvoyer

More photo essays:

Moscow’s Real-Life Fight Club Looks Insane

Artist Abdul Vas Loves AC/DC More Than Anyone On Earth

20 Years in War Zones With Jack Picone

Steph, Summer 2010

Tony Fouhse

Steph sleeping, November 2010

Tony Fouhse

Steph at my house, November, 2010

Tony Fouhse

Steph injecting heroin, December, 2010

Tony Fouhse

Steph’s room

Tony Fouhse

Nelson Street, December, 2010

Tony Fouhse

Steph with material, December, 2010

Tony Fouhse

Cooking heroin, Jan, 2011

Tony Fouhse

After hitting heroin, Jan, 2011

Tony Fouhse

At home, Feb, 2011

Tony Fouhse

Detail, Steph’s room, March, 2011

Tony Fouhse

Steph in emergency, March, 2011

Tony Fouhse

In the Neurology Unit, March, 2011

Tony Fouhse

Steph at my house, three days after brain surgery, March, 2011

Tony Fouhse

At my house, with Gus and Lily, March, 2011

Tony Fouhse

The site of the operation, April, 2011

Tony Fouhse

At my house, April, 2011

Tony Fouhse

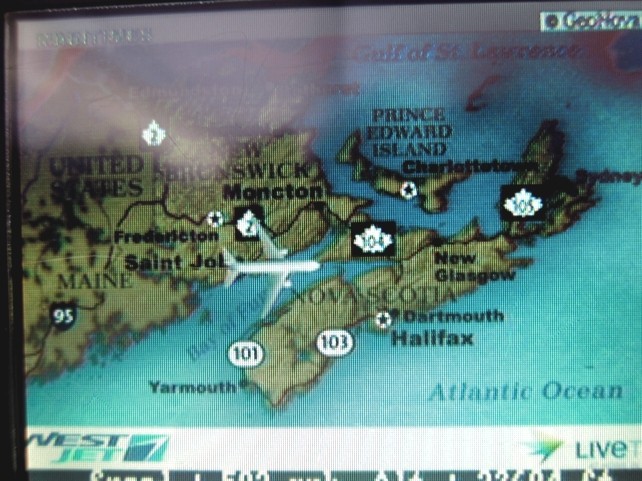

Three months later, going to Nova Scotia to visit Steph, June, 2011

Tony Fouhse

Steph at Westray Coal Mine, New Glasgow, June, 2011

Tony Fouhse

Steph at her mother’s house, New Glasgow, June, 2011

Tony Fouhse

Steph in her room, New Glasgow, June, 2011

Tony Fouhse

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images -

WWE -

Screenshot: AEW -

Photo: Frank Hoensch/Redferns via Getty Images