The bombed out, makeshift “Hotel California” at Baghdad International Airport.

It was October 2003, five months after the invastion, and we were doing the “highway mission” for what seemed like an eternity. Gone were the exciting patrols, snap traffic stops, night raids, and even the dreaded all-day cordon and searches that brought us into the living rooms of everyday Iraqis.

Videos by VICE

This was how it’d play out: our squad, like many other squads, would set up somewhere along one of Baghdad’s busy highways and establish an observation post for about 12 hours before being relieved by another squad. We’d sit, watch, sweat, and leave. Twelve hours on, 24 off. That off time was filled with weapons maintenance, guard duty, “hey you” details, “hey you” missions, chow, rest, and personal time. It was dull. It sucked.

Then, one day our platoon was tasked with sending two infantry squads to Baghdad International Airport (BIAP) for a mystery detail that would last for at least a week. I was a team leader in one of the chosen squads; without knowing exactly what we were doing, we packed our gear and loaded onto a truck while the rest of the platoon looked on with envy. With our departure, their 12 hours on, 24 hours off just became 12 on, 12 off.

After Saddam’s conquered palace in the Green Zone, the airport offered the most luxury available to deployed soldiers in Iraq. BIAP to the airport for a grunt, however short, was a welcome respite from the drudgery of a long war—it had a Burger King, a massive store that was routinely restocked (the PX), and a first-rate dining facility. Soldiers would eagerly volunteer to accompany anyone going to BIAP as extra security just for the chance to be there.

So we were excited as we waved goodbye to the rest of our platoon and rolled out to seek fortune, glory, and a Whopper.

After speeding along Baghdad’s infamous Highway 8, we got to the winged statue that welcomes you to BIAP. Passing through numerous checkpoints manned by nervous American soldiers, our eyes were drawn to a tall sand-colored office building at the center of the airport terminals. On its side was draped a canvas that read, “Welcome to Hotel California.”

Our truck snaked its way to the center of activity near the Hotel California and our platoon leader left to link up with whomever he was supposed to link up with. This left the rest of us with some free time to explore.

The Burger King was the obvious first choice. Earlier in the summer, our platoon sergeant brought back a single chicken sandwich from a trip to BIAP that had to be shared with the entire 36-man unit. Each soldier took a tiny bite and then passed the sandwich to the next guy, this being repeated until it disappeared. As silly as it seems now, that single bite was amazing.

The line at Burger King was always ridiculously long. Wait times of more than three hours were the norm, and by the time you made it to the window, “having it your way” was unlikely since most of their in-demand supplies had likely been exhausted.

Next was the PX, which was housed in an old sheet-metal hangar with an extremely high ceiling. The PX sold a little bit of everything, but the hot items were junk food, magazines, and electronics. These would sell out as soon as they were put on the shelves. Soldiers stationed at BIAP obviously had the best chance of snagging prized goods, which became a point of contention for infantry troops who only got a few minutes to pass through and pick up whatever shit was left.

The dining facility, however, was always amazing. It was named after Bob Hope and a few months later President Bush would fly in and help serve Thanksgiving dinner. For a unit that had subsisted almost exclusively on Meals Ready to Eat (MREs) for months, the sudden availability of normal food instantly raised morale while simultaneously stiffening disdain for the lucky ones who had permanent access to it. You could eat healthy or go to town on French toast, cakes and ice cream. After going there, trips to Burger King happened only for novelty’s sake or if you happened to pass by and noticed the line was short.

After our short tour of the amenities, we were told that our two squads were there to serve as an emergency Quick Reaction Force (QRF) for the Baghdad area. If someone needed a couple infantry squads in a pinch, we would load up on Blackhawks and be inserted wherever we were needed. We passed the guys we were taking over for and the expressions on their faces suggested they were not happy to go.

To us this was an awesome mission template. No guard duty, no nonsense. Just waiting for an emergency call that would whisk us away to a firefight via UH-60s to do the nasty work of infantrymen. In the meantime, we had some of the finest facilities that Iraq had to offer at our fingertips.

Our home would be the seventh floor of the Hotel California, which seemed mostly abandoned except for the ground floor. We slowly climbed the of stairs with all our weapons, ammo, rucksacks, body armor, and personal gear. Legs burning, we finally made it to our floor, which once housed an Iraqi travel agency. Most of the furniture was gone, but there were still some desks and cabinets with travel brochures harking back to a time before the war when Iraqis travelled for leisure. The tall windows were blown out, which let in a welcome cool breeze. The wind whipped past the building, whistling eerily. We could see out over the sprawling airport all the way to where it met the beginning of Baghdad proper. A dark haze sat low in the sky.

The spartan conditions of American life in Iraq in 2003 brought out the latent talents of many soldiers. Amateur electricians became local superstars, and after only a few minutes of messing around ours managed to get some lights on in the former travel agency and jerry-rigged some electrical outlets. With that, the opportunities for what was possible expanded exponentially. Long story short, we bought a TV, an Xbox, four controllers, and a copy of Halo: Combat Evolved.

That evening, under weak amber lights, we gathered around the TV while our electricians put the finishing touches on their setup: connecting wires, taping connections, and double-checking their work. With everything ready, we powered on the TV and then the Xbox.

Before anything appeared on the screen we heard a loud pop. Smoke rose from the Xbox. Our eagerness to start gaming had blinded us to the reality of circuitry outside the United States. The Xbox would only operate on a 110 circuit, and we plugged it into the Iraqi 220 circuit. We were completely bummed, especially the guy who shelled out the cash for the Xbox and TV. It was late and the PX was closed, so we decided that we would go back to the PX first thing in the morning and try to exchange the Xbox under the premise that we plugged it in and it didn’t work (which was true).

The next morning, we again gathered around the setup, plugging our second Xbox into a small orange transformer.

Electricity is a magical thing. It worked.

For about ten seconds, anyway. Then it shut down and burned out—apparently the small orange transformer was only capable of handling minor electronics, not the heavy-duty power needs of a modern gaming machine.

Two Xboxes down, but determined to make this work, we devised a new plan. One of us would try to exchange the second fried Xbox while I scoured BIAP for a transformer powerful enough to handle the Xbox. Strangely, the manager at the PX had no problem accepting a second fried Xbox from the same guy in two days and exchanging it for a third. I guess this happens a lot. In fact, you think they’d just start putting a note in the boxes. Anyway.

I spent the better part of the morning creeping around the airport looking for heavy-duty transformers. After asking around, I learned that there was a hole-in-the-wall store near BIAP run by Iraqis. The store was actually right next to Hotel California, but you wouldn’t know it unless someone had clued you in because it was behind an unmarked door. The shelves were stocked with local food, cheap jewellery, crappy paintings, and other souvenirs—better yet, stowed away in the corner were a bunch of metal boxes of various sizes: the transformers. Although I could have settled for a smaller model, I didn’t want to disappoint the squad. I bought the biggest transformer they had, which weighed at least 30 pounds and was complete overkill for our needs.

Transformer in tow, I made the slow ascent to the seventh floor. When I walked in with the transformer I received loud applause from the men who were gathered around the Xbox, waiting. With more transforming power than we could ever needed we once again set up our system and carefully turned the power on, holding our breath, expecting another sizzle and pop.

This time, we reached the main screen and were greeted with the heroic title music of the Halo series.

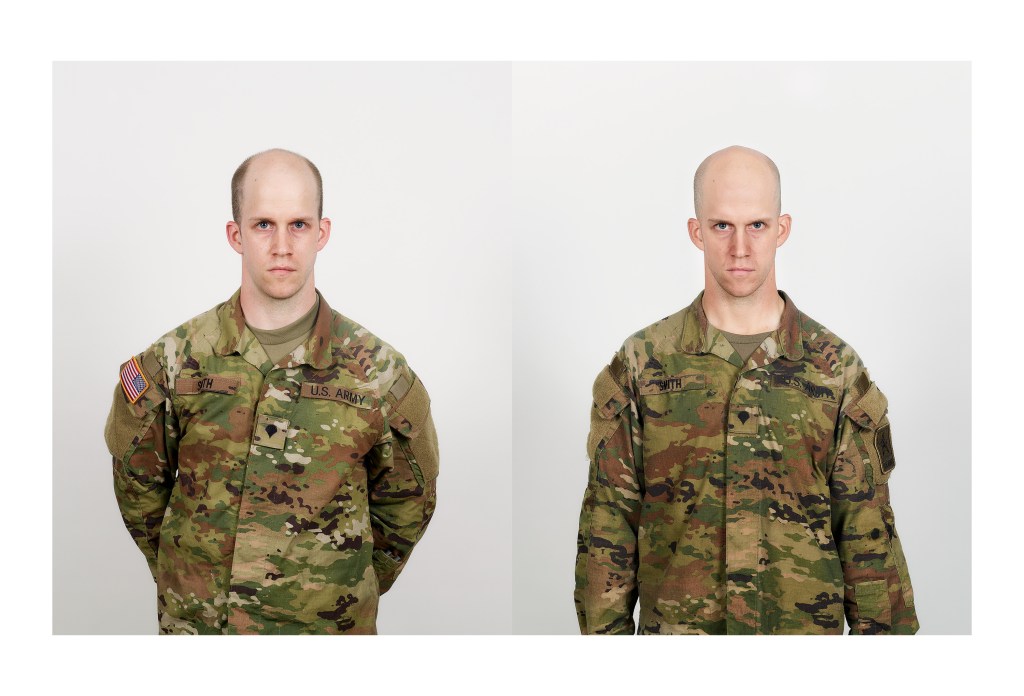

Our squad posing by a Blackhawk helicopter (I’m second from the right).

The next two weeks became an in-country orgy of gaming madness. We were never called for a QRF mission. We never did any actual work at all. We spent our days bringing styrofoam plates piled with greasy food up to the seventh floor and playing four-way Halo tournaments all day long. We gave each other mean nicknames like “Fat Elvis.” If someone got on a hot streak, we changed the game to something we called “The One” (a nod to The Matrix, which we were all a little too obsessed with at the time) and played three-on-one until we all killed the unlucky winner.

We played straight through mortar attacks, glancing briefly out the window to make sure the rounds weren’t exploding too near to our seventh floor retreat. “Eh, it’s not really close,” I’d say without really ever looking away from Master Chief.

Those two weeks seemed to last forever as we settled into our new norm of hot showers, good food, video games all day, and the only threat of work being a sexy mission that would take us directly to the ultra-elusive enemy, where we would close with and destroy him.

When our platoon leader and platoon sergeant showed up to pick us up, we reluctantly packed up our gear and wore the same sad faces of the guys we relieved two weeks earlier. It was like leaving summer camp. Our leadership could sense that we had been getting over, especially as we loaded a couple of big-screen TVs into our dusty truck to be brought back to our humble firebase where they’d be useless without electricity.

Arriving back at the old base, the rest of the soldiers glared angrily as we settled back into our old spots in the platoon bay. Our gifts of Red Hot Cheetos were accepted, but it didn’t change one of our most basic rules: if you got out of the firebase, you were getting over. This was especially true in our case because while we were gone the platoon had to accomplish the same amount of work with half the manpower. And word had spread quickly that we were living the high life at BIAP, despite our assurances that it wasn’t that great.

We would only spend a few more weeks at our shitty firebase before moving to a larger consolidated forward operating base, complete with a dining facility of its own and four-man rooms. There, all of us would get to enjoy the high life a little bit.

But nothing will beat those two weeks at Hotel California.

Follow Don on Twitter: @dongomezjr

Read his blog here.

More on military matters:

I Was David Petraeus’s Bitch in the 90s and I Hated Every Second of It

We Asked a Military Expert if All the World’s Armies Could Shut Down the US

Army Girls Can Be Girly Girls in Afghanistan

How The 2003 Anti-Iraq War March Changed British Democracy Forever