“What the hell is you doing?”

I looked up from my enormous Tupperware of crawfish to find my friend, a 9th Ward native, gawking at the manner in which I had just peeled my first mudbug. I held its severed head, with beady black eyes full of judgment, in one hand, and tried to suck the meat out of the tail. Its fiery cayenne-lemon boil water was stinging my lips and simultaneously inducing a feverish hunger that was growing by the second. I couldn’t figure out how to extract the meat.

Videos by VICE

“Girl, give me that,” he said, grabbing the tail from my hand, cracking it straight down the middle, the long way, between his thumb and middle index finger, extracting the meat—a tiny lobster tail with less pretension, if you will. He then ate it and flicked the shell into a plastic Winn Dixie bag. I took another swig of beer and started over.

New Orleans was a club of which I desperately wanted to be a member. I’d moved to the city a few weeks before said crawfish incident. And while I’d enjoyed the crustaceans during my previous visits, in regional staples such as dip, sausage, beignets, and balls, they’d always been peeled, prepped, and battered up into something decadent but unidentifiable compared to its original form. In order to even appeal to the sorority, I needed to know my way around a crawfish. This was made clear to me early in the game, from everyone to my friends who snickered at me to the Vietnamese seafood shop owners in my neighborhood of Mid City who watched, bemused, as I struggled through the ordering process.

I also needed to conquer the crawdaddies because I was hyperaware of what was happening in this city. Outsiders like myself were moving in from all over the place, not just subletting homes, but hijacking customs and injecting them with unneeded hipster sauce. And frankly, this city is doused in seasoning already. No need for more sauce.

I was determined to not be that outsider. And it took me years to figure out how to peel and eat crawfish (though if you ask certain people, they’ll tell you I’m still terrible at it). I took and continue to take an effort to support black business in a city sturdily built on black culture, so I generally avoided the new places that cropped up and opted for the eateries recommended to me by my students at the community college I taught writing at—places their families had gone to since they were in diapers. Through the étouffées and gumbos, doberge cake and bread pudding, char-grilled and fried oysters, I’d always return to the crawfish as a lighthouse of sorts. I couldn’t shake the idea that they were some type of mascot for the city: I’d sometimes be sitting at Katie’s, or some other venerable New Orleans restaurant, with a napkin on my lap, merking a crab cake flatbread but thinking about my antler-adorned mistress, the orangey-red crawfish waiting for me, perched atop a pile of her friends at one of the shops on Claiborne.

And the ritual is not just about cracking claws, it’s about where you eat them and who with. I’d sometimes go the Pontchartrain lakefront with my friend Dez and her husband and their several kids on Sunday afternoons where families would come with aluminum baking pans of boiled crawfish, shrimp, sometimes crab, potatoes, boudin, and corn. When my friends from home visited, we’d crack shells out by the pool in my building and I’d chide them about how slow they and inept they were at it.

It’s about your etiquette, too. I once got in real trouble with my ex because I ate crawfish on his porch, got the juice everywhere, dumped the shells in the garbage can in 90-degree weather, and then happily sprawled onto his bed and started scrolling through my IG feed without washing my hands and face. It is mandatory to clean the hell up after you indulge, even if you’re outside, which is where most people eat boiled seafood. You have to spray down surfaces, use some kind of solvent, and then dispose of all the evidence. If you don’t, there are dire consequences for you and those within a mile’s radius. When you’re in a city shaped like a bowl, these consequences include roaches, ants, maggots—all the magnificent creatures that emerge from the earth, driven by their love for anything fishy. The ex was supremely offended by my nonchalant post-crawfish behavior, as if I had violated some kind of seafood samurai code. Indeed, I’d brought shame upon the family.

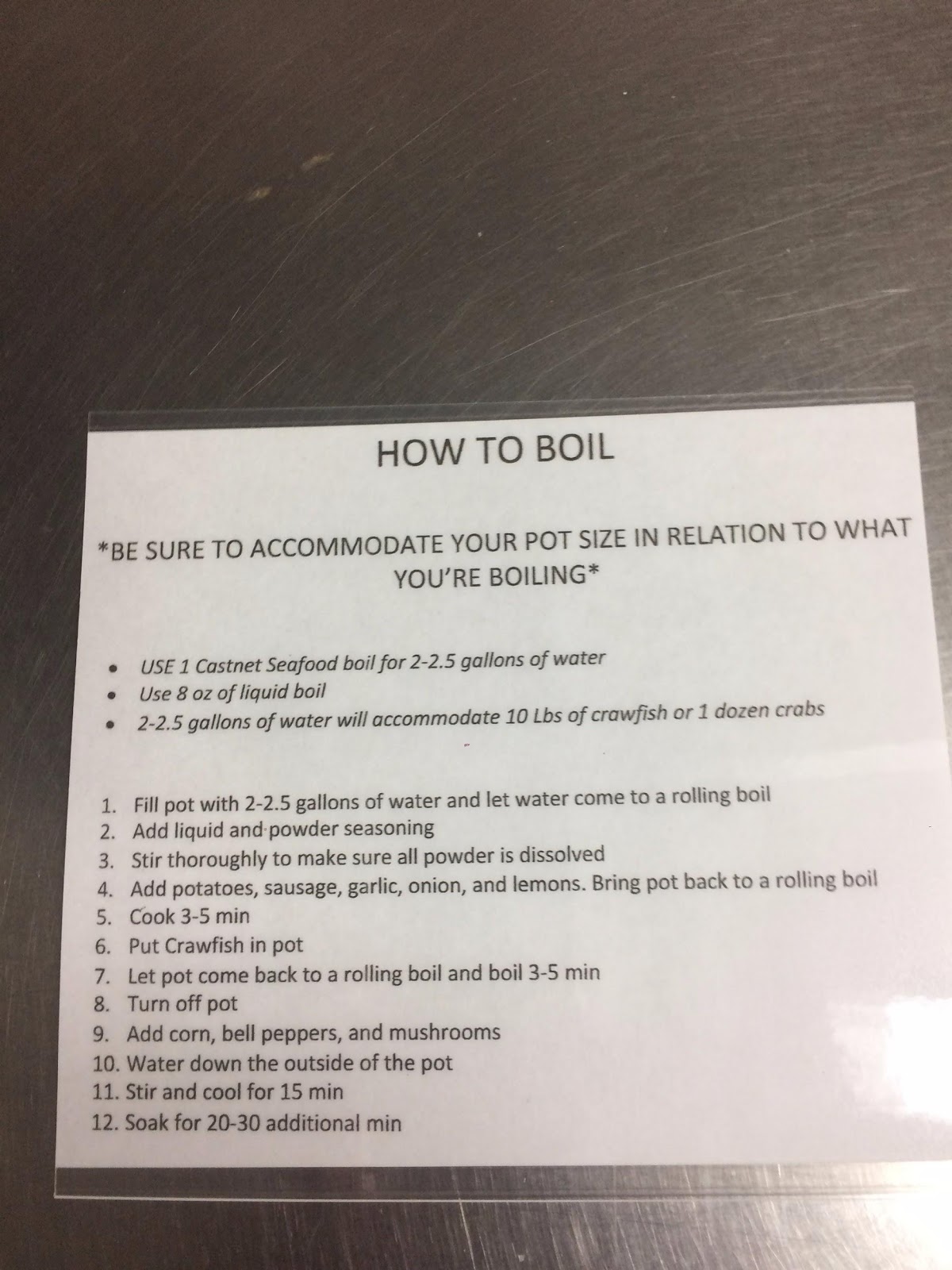

But see, it’s hard to mind your etiquette when you dive into a boil as an outsider. New Yorkers like myself generally don’t know shit about this life. I get sprung off the flavors every time, even now that I’m fully acquainted with experienced the melange of essence profiles in a typical boil. Kent Bondi, the owner of Castnet, my favorite seafood spot in New Orleans, broke down the entire process of how to do a boil for me (and even sent a picture of their recipe, which I included so you can try it for yourself if you don’t live in a tiny studio like I do.)

The most important part of this process, he tells me, is getting the water—or boil juice, as I affectionately call it—right before you drop the mudbugs in. This involves combining a dry spice mixture and a liquid seasoning, both of which can be bought prepackaged, but shops like Bondi’s tend to make their own. “We season water; we don’t season crawfish,” he tells me in his deep drawl. Regardless of what’s in the boil, though, that cayenne presence is heavy, glorious, and an energizing, searing reminder of where the hell you are.

And then there are the veggies, the “holy trinity” of New Orleans seasoning: onions, celery, and bell peppers, plus garlic and lemon. Bondi’s is a version of the classic blend historically attributed to the Cajuns of southern Louisiana, who are, let’s be real, culinary royalty. Bondi isn’t a Cajun, but he was born into the seafood game; as a kid, he worked for the small neighborhood shop, Joyce’s, learned the ropes, and eventually bought the place when he was 19.

Nearly 30 years later, Castnet is a highly respected mudbug institution, teeming with fresh scaly and shelled creatures—both raw and cooked—available for takeout. The shop was a little out of my way when I lived in New Orleans, but I’d make the trip anyway. Even my pedestrian tongue could tell the difference between mass-produced, careless boils and ones stirred with intention.

Back in New York and staring down at this recipe, I was sure Bondi would keep from me, I was tempted to try it at home. I’d have to get the little guys shipped and I’d need to borrow a kitchen significantly bigger and better ventilated than my own (a converted closet, thanks Manhattan). I quickly ousted this idea and instead opened my flight app to book my next trip to the Boot.

See, I promised myself, when I lived down there, to never turn into one of those d-bags who gets a fleur-de-lis tattoo, pretends that they can twerk like Big Freedia, and stir a roux like somebody’s grandma. I still grin—I can’t help it—every time my friend Crissy’s mom says I look like I’m from the 7th Ward until I open my mouth and talk that northern talk.

I am an outsider. And that’s okay. That city fully embraces a loyal groupie who knows how to crack a shell.