David Lynch making a video game feels incongruous.

Over the years, Lynch has produced a disproportionate diversity of work: collaborative dream-pop; crude, lighted sculptures, the odd rectilinear furnishing; enough phantasmagorical mixed-media to swallow you in perpetual night terrors; and, once, the interior designs for a Parisian nightclub.

Videos by VICE

Now try picturing him hunched over a laptop, as if the spirit of Francis Bacon were tinkering away at a little Unreal Engine world building. It doesn’t quite fit. In theory, computer code seems too rigid a medium for the free-flow Lynch, who has claimed on countless occasions that he’s not entirely sure how or if he is in full control of his ideas. Few developers have tried to shine a light on what is “Lynchian,” either, with clear echoes toward his creative trinity—dread, the abstract, and the absurd—few and far between in interactive media.

Still, one fleshy piece of Lynch has burrowed its way deep into video games, and that is the essence of Twin Peaks. There’s no shortage of archetypal appeal here: an eclectic cast of miscreants and weirdos, creeping, shapeless fear (often punctuated by lingering synth), or just the tawdry thrill of a one-horse town where everyone has something to hide. Depending on the audience, they all have their charms.

And as deliriously vertiginous as the series’ improbable third season revival has been, it’s just as fun to imagine the twisted interactive forms its inspirational appendages might take down the road. Television as brazen as 2017’s Twin Peaks deserves a good complement.

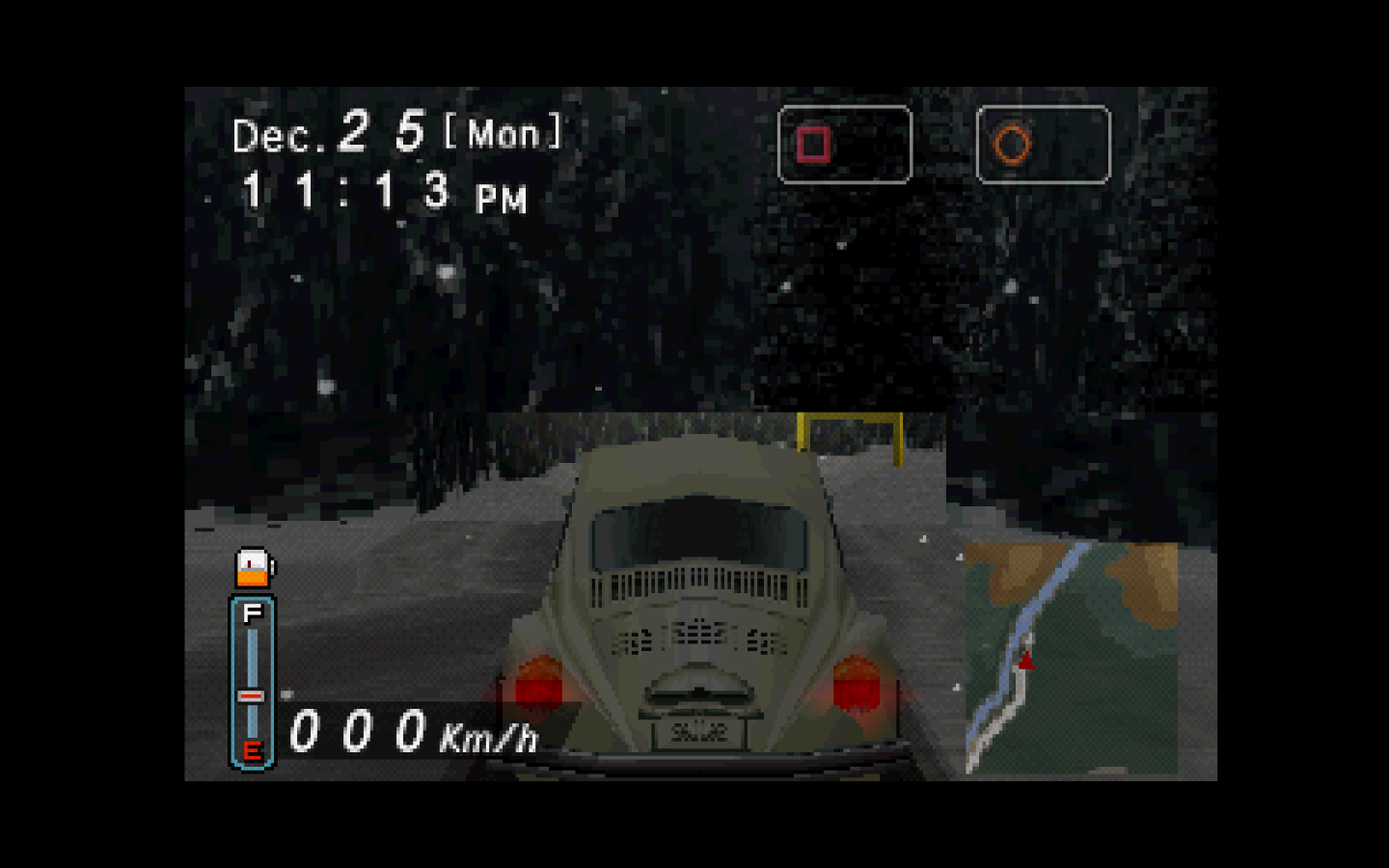

Above: The intro to Mizzurna Falls

As it stands, video game homage show as much overt affection for the source material as any you’ll find elsewhere. It’s not hard to notice the pronounced, sleeve-wearing tributes that do exist, like Remedy’s Alan Wake or Swery65’s demented Deadly Premonition, for instance. But there’s another that’s lesser-known: 1998’s esoteric Mizzurna Falls, a quaint, creaky open-world mystery produced in Japan for the original PlayStation.

Virtually unknown since the time of its release, Mizzurna is an enigma that describes itself as “a country of the woods and repose” on its title screen—a Peaksian designation if ever there was one. The game follows Matthew, a determined high school student who gets tangled up in a series of bizarre events following the disappearance of his friend, classmate (and Laura Palmer stand-in) Emma Lowland. Whatever concealed truths the town may be hiding, it’s up to you to unravel them.

Except, English-speaking players have never had that chance. As a strictly Japanese-language release from the now-defunct Clock Tower developer Human Entertainment, Mizzurna Falls was never localized for the west. (In another strangely appropriate denouement, writer and director Taichi Ishizuka never made another a game, leaving development entirely to pursue a career as a nature guide in Canada. He’s still there.) Short of buying a copy in its native tongue, the only way to play Mizzurna is via emulation, though it proves little more than a 20-year-old curiosity without proper access to its dialogue-dense script.

Now, that’s no longer the case. Thanks to the devoted work of Tokyo-based freelance translator Resident Evie, that script is more accessible for English language audiences.

Like most of the western world, Evie, who asked Waypoint not to use her full name, wasn’t familiar with Mizzurna Falls when she stumbled across it for the first time in the Autumn of 2015. A devout fan of Twin Peaks, Deadly Premonition and Lynch, experiencing Mizzurna had such an unexpectedly profound affect on Evie that she wanted to spread the word to others, leading her to start a narrated playthrough on Youtube for players lacking fluency in Japanese.

“Originally I didn’t have any plans to translate [the script], or any of this,” she says. Actually, on Youtube I was playing blind, so I had no idea what I was getting into. But once I finished the game I realized a lot of other people would really enjoy [it].”

Today, she’s been through the exhaustive process of creating a full English fan translation—thousands of lines of text, including item descriptions, rare NPC dialogue, and other hidden odds and ends.

If translation alone wasn’t enough, Evie has kept up a comprehensive record of her progress on her Tumblr Project Mizzurna, which serves as much as a repository for walkthrough materials, thematic discussions and other notable tidbits as it did at the time for project milestones. But she never intended for much more than to expose Mizzurna to whatever audience her livestreams attracted.

“This is just the kind of game I’ve always wanted to play,” she says.

Her fascination is understandable. Though the PlayStation boasted just 2mb of RAM, Mizzurna’s free roaming design demands you get around the town and surrounding countryside by car, as the game’s wide cast of characters go about their individual routines in the background, day or night. The programmers even included a full weather cycle and Quicktime events.

“It’s interesting, when Silent Hill came out, everyone was saying, ‘Ah, you know, the town is so big, how did they do this on PS One?’” she says. “ Mizzurna Falls did the same thing at almost exactly the same time, but nobody knew about it.”

Seams do show, naturally. Stands of trees are common fodder for abrupt pop-in as your generic VW crawls over the road, and most buildings are merely a façade. Regardless, it’s no small feat that Ishizuka and his tiny team could harness PS One’s power to engineer a series of systems similar to the Dreamcast’s Shenmue, which would be hailed as nothing short of revolutionary when it debuted on Sega’s vastly more powerful hardware a year later. It may not have looked it, but Mizzurna was a technical marvel, no matter of platform.

“It’s pretty amazing how they squeezed it all in on the PlayStation,” Evie says.

Between its accomplishments and any Lynchian ties, it’s puzzling that Mizzurna has gone almost two decades hardly registering as more than a blip on anyone’s radar. It was also what Evie found so fascinating about it.

“One day I was just googling games similar to Deadly Premonition, and I saw a Tumblr post from a few years ago where someone had written a summary of [Mizzurna Falls],” she says. “That was pretty much the only thing on the internet in English about it. So I was obviously interested.”

Not that Mizzurna‘s online presence in Japan is much bigger—a somewhat baffling reality, when you consider the maniacal response Japanese fans have historically had for all things Twin Peaks.

“It’s very hidden,” Evie says. “Even on the internet in Japanese there’s not actually that much about it—just a few fansites, a few Let’s Plays on Youtube. That’s it, really.”

Evie finished her translation last February, posting the game’s script alongside an intricate guide on GameFAQs. At that point, she considered the project effectively finished, and it probably would’ve been if it weren’t for Gemini, an independent developer who hacks old PlayStation-era games.

Coincidentally, Gemini happened to livestream a just-for-fun hacking session for Mizzurna that May, which focused on adding English text to the game. By a stroke of dumb luck, a translator watching the stream told Gemini about Evie’s work.

“I always thought it’d be brilliant if we could put [the text] in, but I knew I couldn’t do it,” Evie says. “Then [Gemini] contacted me saying, ‘I can do this, do you want to provide the English?’ And I said, ‘yes, that would be amazing.’ I never thought that anyone but me would care that much.”

While the release date for Mizzurna‘s translation patch is up in the air—Gemini is also busy with other fan homebrews and hacks, including contributions to restoring Resident Evil 1.5, which Capcom gave the axe in 1997 despite being nearly finished—Evie recently posted some updates with screens and videos of his handiwork. In glimpsing just a few snippets of gameplay, Ishizuka’s writing chops are clear.

“There’s so much depth to [the script]. You don’t really see that so much in video game stories these days,” Evie says. “Usually there’s a story as an excuse for having a game, but this kind of felt the other way around—like there was this really great story and they made a game to tell it.”

Mizzurna is also notable in the ways that it’s distinct from other Peaks inspired games. As anyone who’s played Deadly Premonition can attest, its characterizations often take the notion of Lynchian wackiness to an almost elastic extreme. (Case in point: how often protagonist and FBI lawman York talks to his imaginary friend Zach in front of other characters, who awkwardly pretend not to notice.)

Think of Mizzurna as the other side of the coin, with a cast and mood a bit closer to how Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost originally presented the removed strangeness of how they envisioned the remote Pacific Northwest.

“The humor in Mizzurna Falls is a lot more subtle. And you don’t really get into the minds of the characters as much,” Evie says. “It’s more like it’s the town and what’s happened there is the focus of the story—which is a bit more similar to Twin Peaks.”

That subtlety extends to the surreal, as well.

“The interesting thing about Mizzurna Falls is that you never know whether there’s something supernatural going on, or whether it’s all real,” she says. “Whereas in Twin Peaks and Deadly Premonition, you know straightaway that this could not actually happen.”

This is an important distinction, given how litigiously Mizzurna‘s fuzzy pre-rendered intro cribs from the Twin Peaks aesthetic. The opening titles accompany soft, lingering shots of the eponymous falls, a swinging traffic light, and a replica Double R diner alongside tranquil scenes of nature. With its visual cues priming unsuspecting players, they might guess they know what they’re in for.

Instead, in the opening minutes of the optional prologue, Matthew gets a phone call from Winona, a close mutual friend who tells him that Emma is missing. Soon thereafter, he learns that a second schoolmate, Kathy, is in the hospital after an apparent bear attack. There is immediate suspicion that the two incidents may somehow be linked, and before Matthew can say much to local law enforcement Kathy regains consciousness, prompting him to accompany the sheriff to the scene.

Narrative setup aside, you’ll want to play through this opener simply because it isn’t timed. Navigating Mizzurna‘s world can be a bit unwieldy; in its defense, the design isn’t that far removed from a still-playable classic like Silent Hill, handling movement via clunky rotational tank controls and and encouraging an investigatory nose for exploration.

Until you leave the hospital, the training wheels are on. After that, the in-game clock starts ticking down the seven days (possibly an oblique nod to Lynch’s Twin Peaks prequel Fire Walk With Me) you’re given to solve everything. Gameplay tics like these are hardly out of the ordinary for 1998, yet trying to find the exact point within a 3D space to interact with an object is a finicky process without the precise inputs expected in modern games. It takes a little getting used to.

Mizzurna is also far from a cakewalk. A mystery in the truest sense, the game expects players to piece together clues by thinking like a sleuth, using the entire map as a canvassing area as they move from one investigation thread to the next. Mundane details work against you, too: Saving your game jumps time ahead, and you have to watch how much gas is in your tank. There’s no A for effort here—when those seven days are up, the story ends.

“It’s really fascinating how the real-time aspects of the game work, because [it’s] exactly how [limited] time really works,” Evie says. “It’s a very unique concept—it doesn’t necessarily work as well as it could, but it’s definitely something that I’ve never seen in a game before.”

That means something as simple as forgetting to talk to a particular character could make it impossible to continue later, as initially happened to Evie when she had to make a phone call to someone who did not pick up because Matthew hadn’t spoken to them previously. It’s the freedom of choice across an open world that gives Mizzurna its unforgiving edge, Evie says.

“There are so many [ways to fail], it’s extremely difficult. And the game itself doesn’t tell you what it wants you to do, it only ever hints,” she says. “I don’t think too many people could get it right the first time. I really would be surprised.”

Unlike in Shenmue, you can’t afford to get distracted.

“You really don’t have any time to go sightseeing or anything like that,” Evie says. “It can be quite stressful.”

The end result wasn’t Ishizuka’s original intention. In an interview republished on Project Mizzurna, he expresses some regret that certain systems weren’t implemented to help players out.

“There were things that he wanted to do to make it easier,” says Evie. “It is a very difficult game, and I do think that probably put a lot of players off. If you don’t know what you’re doing, it’s really, really difficult to get the true ending.”

A lack of coddling shouldn’t be a deterrent. It is possible for players to finish the game without resorting to a walkthrough—the clues are all there, if you’re smart about finding them—and that, perhaps like Twin Peaks‘ return, one of the biggest pleasures is in how the plot goes to places you would never guess.

This is how Mizzurna best exhibits a Shenmue sensibility, as Matthew must endure bar fistfights, animal attacks, car chases and tailing suspects without being spotted, to name just a few random scenarios. As much as Evie likens Mizzurna to a really great story that a game was made to tell, so the design seems to follow suit.

“The gameplay is always changing, so it’ll introduce something almost at the end of the game that you’ve never done before,” Evie says. “There are so many moments like that.”

She maintains it’s the narrative alone that’s worth the price of admission, crediting a cross-country trip Ishizuka took across America before development began as a primary reason for its authenticity beyond the director’s obvious love of Lynch. (The only oversight in Mizzurna‘s Americana? The fact that a game taking place starting on December 25th is oddly staged in a town devoid of Christmas decorations.)

“Apart from that, it’s really, really well done,” Evie says. “And it’s a brilliant game to translate because it’s so well written. You don’t always get that with Japanese games.”

Ironically, Lynch did flirt once with the notion of games in the mid-’90s, in a planned collaboration with a trio of Japanese companies, including Bandai. It’s doubtful the project, called Woodcutters From Fiery Ships—which may or may not have been related to the tar-faced Woodsmen of Fire Walk With Me and 2017’s revival—ever had a realistic shot at going anywhere, if Lynch’s own dreamlike description of an experience that could “bend back upon itself” is any indication. The purest of Lynchian forms may be anathema to such digital spaces.

If Twin Peaks’ weirder side is covered with the greatest frequency, then Mizzurna Falls gives players an excuse to live in a different sort of Lynchian dimension. Having now finished the game countless times, Evie is thrilled at the possibility of its gaining real exposure to curious players willing to seek it out—and to Twin Peaks fans.

“Finding this game for me was just amazing, because it was more of what I really like about Twin Peaks,” she says. “I like all the weird, crazy stuff—but I also like the notion of this peaceful town where something is really bad is going on. So, for me personally, it kind of satisfied my desire for that side of it.”