Hanging Rock is a popular tourist spot in central Victoria, about an hour from Melbourne. It’s a moody place—eerie, arresting—made famous by Joan Lindsay’s 1967 book, Picnic at Hanging Rock, and infamous by Peter Weir’s 1975 film of the same name. Every year fans flock to the landmark, attracted by the mystery of Lindsay’s missing schoolgirls. It’s even custom to cry out “Miranda!” at the top of the rock.

Down at the base, you’ll find an “interpretative Discovery Centre” where visitors are enthralled by life-sized dioramas and video displays about the schoolgirls who mysteriously disappeared in Picnic at Hanging Rock. Of course, none of it ever happened. No matter how ambiguous Lindsay was about the origins of her story, there were never any schoolgirls who vanished at Hanging Rock.

Videos by VICE

Yet amidst the obsessive retelling of a fictional disappearance, there’s hardly a mention of the area’s Aboriginal people, nor of their very real removal and displacement. It barely rates a mention.

Of course, Hanging Rock is just one landmark in the vastness of Australia where history seems to begin only after 1770. But it’s not for lack of interest in stories about the land. We are obsessed with lost-in-the-bush stories, as long as the hero is white. The lost Duff children in Western Victoria, the White Woman of Gippsland, even the tragedy of Azaria Chamberlain. These are all stories told repetitively and remembered. But when do we remember, retell, and mourn frontier slaughters of the original landowners, or the lives of stolen Aboriginal children? It just doesn’t happen.

It’s a phenomenon cultural theorist Elspeth Tilley explains as “white vanishing.” She notes “how good non-Aboriginal Australians are at memorialising their own sufferings.” For millennia though, Aboriginal history was passed down from generation to generation in an oral tradition—stories told and remembered, rather than written down. The problem is that when the people disappeared, so too did their stories. The absence of visible Aboriginal history at Hanging Rock doesn’t mean there’s no story to tell. Rather it’s evidence of a violent and destructive wave of colonisation that passed through the region.

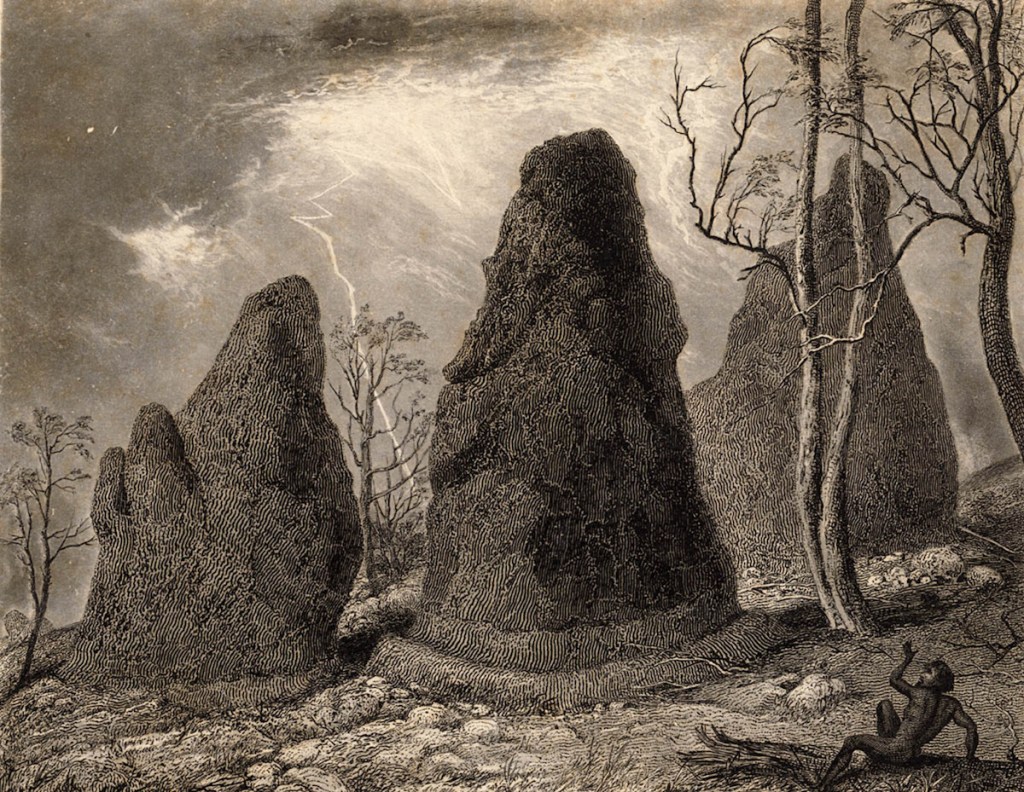

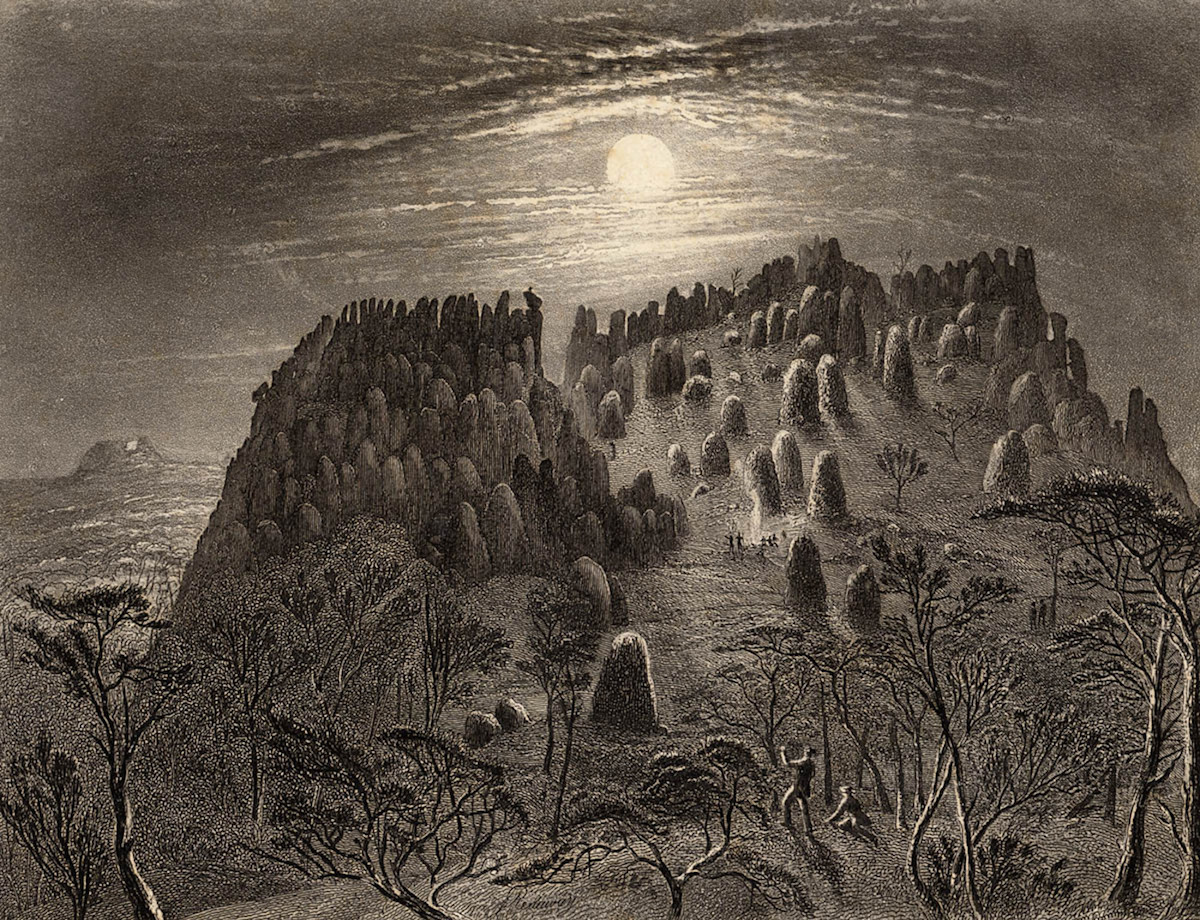

Etchings by the German zoologist William Blandowski, made during his 1850s expeditions into central Victoria. He was one of the first Europeans to describe Hanging Rock, as it’s now known.

From what we do know, the traditional owners have lived around Hanging Rock for more than 26,000 years. It’s believed the Rock was an important inter-tribal ceremonial meeting place, and a significant landmark on the boundary of three different groups—the Wurundjeri, Taungurong, and Djadja Wurrung.

Yet attempts to uncover Hanging Rock’s Aboriginal name have proven difficult. Some think it is “Anneyelong” because of an inscription underneath an engraving of the rock made by German naturalist, William Blandowski, during an expedition in 1855-56. Historian and toponymist Ian D. Clark believes Blandowski misheard the name, and the word was possibly “Ngannelong” or something similar. The evidence does tell us that when Europeans settled the region, huge numbers of Hanging Rock’s Aboriginal population died and were forcibly removed from their land. Many suffered from introduced diseases, such as outbreaks of smallpox. Then in 1863, the Aboriginal people who survived disease and conflict with settlers were rounded up and relocated to the Coranderrk Aboriginal Reserve in Healesville.

Visitors barely register this information at the Hanging Rock interpretative Discovery Centre. But they do read all about how three schoolgirls from Appleyard College and their governess vanished from the summit of the rock on Valentine’s Day in 1900. Hanging Rock, it seems, is haunted by a convenient fiction rather than an uncomfortable fact. On the whole, Australia’s understanding of its own history has been described as a nursery book version, a palatable, whitewashed fairytale that avoids recounting the evident violence and destruction of settler colonialism. We’d prefer to tell comfortable tales of schoolgirls going missing in the bush than face our past. As writer Bruce Pascoe reminds us: the history has not gone away—we just choose not to see it.

Could we do better? When Australians are faced with evidence of absent Aboriginal lives, mass destruction, and lost culture, why do we choose to overlook it? Shouldn’t we acknowledge their loss in potent, affecting panels, artworks, and monuments? Artist Horst Hoheisel’s bold but unrealised proposition for a Holocaust memorial in Berlin provides a powerful anti-monument to absence. Rather than commemorating the destruction of a people via a new construction, Hoheisel proposed instead to blow up the Brandenburg Gate (the symbol of Berlin). “How better to remember a destroyed people,” Hoheisel asked, “than by a destroyed monument?”

Black Lives Matter activists in the US have insisted on honest discussion of the nation’s history—campaigning for the removal of confederate monuments and symbols. And as writer Jeff Sparrow argues, “if black lives really matter in Australia, it’s time we owned up to our history.” Sparrow has called for similar grassroots campaigns to identify and commemorate Australia’s troubling frontier past. These, he says, must involve localised activities aimed at drawing attention to specific histories in specific places, like Hanging Rock.

It’s for these reasons that I started a campaign called Miranda Must Go. Hoheisel was right: the only way to make people fathom loss on a mass scale is by taking away one of own beloved cultural icons. Our addiction to mythic vanishing whites must stop. We need a detox: a moratorium on Miranda. By ditching our obsession with the disappearing schoolgirls of Hanging Rock we can create space in the landscape to remember Aboriginal people, their losses, and incredible survival despite white Australia’s efforts to destroy them for 229 years.

But this is just one campaign in one location. There needs to be hundreds, thousands of others aimed at challenging the white narratives that dominate across Australia. It’s time to let go of our comforting nursery tales and address our past like grown-ups.

You can find out more about #MirandaMustGo and how to get involved here.