There’s a moment in Dominic Sangma’s 2016 film Rong’Kuchak ( Echoes) in which the reclusive protagonist—a Garo poet from Meghalaya—looks up from his table in a seedy restaurant in Kolkata and finds three young Garo people sitting adjacent to him. “These are my people!” he says to himself in Garo, “They don’t seem like my people.” The film is poignant, with long, slow shots that are sprinkled with magical realism. At the core of the story is a poet’s obsession to make his language (Garo has no written script; the community uses the Roman script to express it) an entity to reckon with amongst the current generation. And yet, on a macrocosmic level (and for the purpose of this piece), this aching sentiment of loss and hope can be repurposed to contextualise the gap between a mainstream audience and the exciting, growing northeastern film industry.

Sangma’s film—his second in Garo—is one of the many contemporary narratives that want to send a message loud and clear: That if you don’t know the cinema from the northeast, you’re missing out on an expression that is way ahead of the mainstream Hindi curve. Sangma’s inadvertent ode to bridging a larger cinematic gap—with a visual language reminiscent of Andrei Tarkovsky and Bela Tarr—between the films that come from the northeast and the larger audience, is a preamble to a movement that many miss every year. And the filmmakers from the region are not going to wait for the world to sit up and notice.

Videos by VICE

In the Bubble

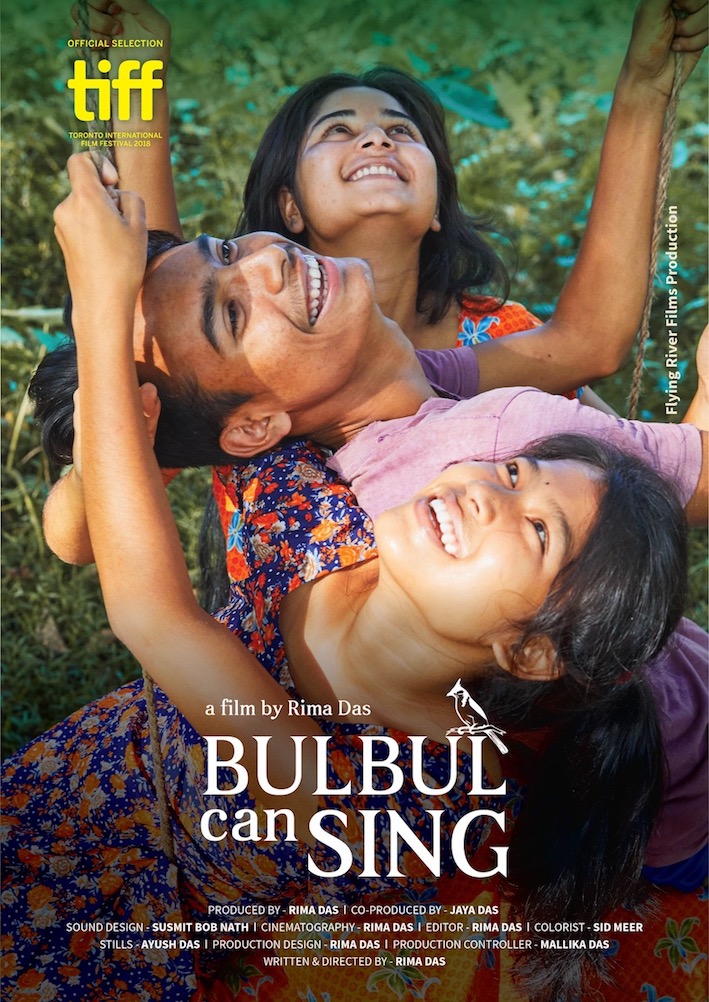

Every now and then, the film festival-trotting audiences in India are jolted out of their bubbles when an extraordinary story from the region makes an appearance. The most recent headlines were made by Mumbai-based Assamese filmmaker Rima Das, called Village Rockstars—about a 10-year-old girl from a tiny village in Assam who dreams of forming her own rock band—when it found wide acclaim at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) last year, and won the National Award for Best Film early this year. Her latest film, Bulbul Can Sing, is a part of the ongoing TIFF lineup (September 6-16) and is already garnering good reviews.

However, stories such as Das’s are not rare. In my pursuit to find new forms of narratives from the region this year, it was fairly easy to stumble upon this climate of discontentment.

“Turbulent political climate is the least of the problems,” says Delhi-based Assamese filmmaker and film critic Utpal Borpujari, “It’s quite peaceful now, in fact.” However, the big problem of lack of funding and public spaces to screen the film still persist. “Even in a state like Assam, where there is a potentially huge viewer base of Assamese cinema, the number of halls are pathetically low. Add to that the fact that most films get just two shows per hall per day the maximum, and many get just one show.”

Another issue is that of the low-quality content of most films, especially in Assamese and Manipuri cinema. “In recent years, barring a few exceptions, mainstream cinema in both states have become caricatures of B-grade Hindi or Telugu movies, which follow a set formula of a few song ‘n’ dance routines, some fight sequences, over-the-top-acting, et al, all held together by a flimsy storyline,” says Borpujari, whose film Ishu won six Assam State FIlm Awards and four at the Prag Cine Awards, along with the National Award for the Best Assamese Film in 2017.

Shillong-based filmmaker Wanphrang K Diengdoh—whose upcoming film, Lorni, featuring actor Adil Hussain, is one of the most anticipated films this year—further recognises the “burden” of the filmmakers from the region. “[They] are forced to carry or rather enjoy the self-flagellation of creating visual content that is either related to militancy, traditional anthropology, tourism and the general image-making that attempts to make an exotic facade of the area,” he says. He likens it to the privilege of colonial anthropologists of the 1800s, focusing on “the right of the ‘indigenous man’ with a camera to create a spectacle of his own self”. “There is an entire generation of kids in urban spaces who are torn between tradition and modernity,” he adds, “Like me, for example. I did not grow up in the village nor did I wear traditional clothes except for maybe once a year at a festival. Do I want to know more about myself and my history and my identity? Yes, of course. But would I parade myself as this exotic being to satiate the gluttony of mainland India’s appetite for the northeast spectacle— no!”

The Problem of ‘Phlim Packez’

The issue begins with the mainstream media and the “event wallahs” of film festivals. And rightly so. Amid the queues for tea, washroom and talk sessions, a certain lethargy has been observed at film festivals, especially towards the “packaging” of films from the northeast.

“I hate the exoticisation of the northeast. It’s very true that northeastern films or filmmakers are, most of the time, clubbed together as if ‘northeast’ itself is a state. You don’t get to see such things from other parts of India,” says Sangma, who will be releasing his latest Garo fiction film, MA.AMA, based on the true experiences of his father. Diengdoh adds, “All the states in the northeast are different. Heck, half-an-hour away from Shillong and there’s a totally different dialect altogether! How can you box all of it in a ‘ phlim packez‘? This is as problematic as assuming all of India is the same.”

One form of subversive force to dispel the homogenised idea of the region “as perpetrated by mainstream Bollywood” comes with what Diengdoh calls the ‘Khasi New Wave’. “They are stories straight off the streets, not shying away the grim realities that we face in the state. I think it is a wonderful opportunity for me to be an image-maker and document this transition so that we can further problematise pre-conceived notions of what an indigenous society is supposed to be like.” This documentation of the evolving indigenous Khasi identity is a part of a larger idea that “regional films will bear a more truthful testimony to a reality of time and space in the country,” he says.

This sense of alienation has extended to III Smoking Barrels, which is arguably the most mainstream production that has come from the region this year, directed by Mumbai-based filmmaker Sanjib Dey. The film ran into some trouble with the Censor Board because it features six different dialects from Assam. “The Censor Board doesn’t have the terminology called ‘multilingual’. It’s astonishing! Right now, my film has received the certificate of an English-language film when I’ve barely used a smattering of the language,” says Dey.

Silver Lining Playbook

It is, of course, hard to ignore the deep-rooted attitude towards the northeast in this context. National Award-winning director Bhaskar Hazarika, for instance, sees this “insidious condescension” trickle down to the attitude towards northeastern films. However, he feels that film festivals do help channel a certain kind of nuance around northeast cinema that busts these myths. “Moreover, northeast-special film festivals are of great value because filmmakers find avenues to exhibit their work outside the NE,” says the director whose latest film Aamis—a love story set in Guwahati—found funding at Busan’s Asian Project market last year and is set to premier early next year.

The sense of hope amid all cynicism is not entirely dead yet. Festivals are still one of the few credible spaces to showcase their work and gain recognition. Monjul Boruah—a young filmmaker from Assam who is also the nephew of the famous filmmaker Jahnu Barua—is currently preparing for the release of his second film Kaaneen (A Secret Search), an adaptation of Assamese author Rita Chowdhury’s book. And he has “undiminished trust” in film festivals and awards in India. “This is regardless of the fact that my [first] two films were never screened at any big or famous festival. I have no idea or experience in marketing or packaging of a film but I am optimistic in the capacity of honesty and hard work to be fruitful,” he says.

Sange Dorjee Thongdok—whose films in the Sherdukpen dialect from Arunachal Pradesh have been a part of film festivals such as the Dharamshala International Film Festival—talks about the problem of recovering the cost of the film if it weren’t for the film festivals. “In this age of digital media, it isn’t very difficult to make a film. Marketing and distribution, however, is a whole different matter, especially for independent cinema, which doesn’t get much support as it is. It becomes extremely difficult to recover the cost of making a film if there is no support for distribution or screenings. Today, if one wants to see an independent film from any region of India, there are hardly any options available. I would love to see more independent cinemas being made in my country, but where [else] do I go to see them?” says the director, whose upcoming film River Song in Sherdukpen will be released this year

As the pressure on the filmmakers who showcase at festivals mounts with every passing year, Diengdoh concludes with an imperative connection between the media and big corporations, and their role in supporting the diverse art practices from the northeastern storytellers. “I firmly believe that sometimes, rather than just nibbling from the hand that feeds us, it is also important that we chew it,” he says. And that, perhaps, is where change really lies.

Follow Pallavi Pundir on Twitter.