The area known today as Crystal Palace occupies a relatively small and quiet spot in South London. In 2017 it is probably most famous for the Premier League side of the same name, though they haven’t played in Crystal Palace itself for more than a century. It is roughly defined, straddling five London boroughs, and includes a vast park and a more modest town centre. In many respects it appears to be an unremarkable place, save for the collection of Victorian-era model dinosaurs that make their home at the lower end of the park.

But while the travails of Wilfried Zaha and co. account for the most column inches, Crystal Palace’s sporting history is in fact hugely varied, encompassing athletics, motorsport, and a 20-year stint hosting the FA Cup Final.

Videos by VICE

One of the anatomically iffy Crystal Palace dinosaurs. This handsome chap is a Megalosaurus, apparently.

Until the mid 1800s the area was largely rural and difficult to access, not that there was much call for people to travel there. In fact, it was not even known as Crystal Palace.

Of course, the Victorian era was characterised by vast and rapid change, a trend encapsulated by the Great Exhibition that ran at Hyde Park between May and October 1851. This unabashed celebration of culture and industry proved a resounding success and, when its initial run ended, talks began about extending its use beyond Central London.

Eventually a consortium purchased the exhibition’s enormous glass house – dubbed ‘the Crystal Palace’ by Punch magazine – and relocated it to the Penge Place estate in Sydenham. The area was renamed Crystal Palace and a new railway station was built to deliver visitors to the attraction. (It is no coincidence that one member of the consortium and the owner of Penge Place was Leo Schuster, a railway entrepreneur who stood to profit greatly from the new line).

The Crystal Palace was a truly enormous structure that dominated the local skyline

With the grandeur of the glass house, spectacular fountains and the aforementioned dinosaurs, it could be called Britain’s first theme park. The move was a success, with the park becoming a tourist draw and new housing mushrooming throughout the area, so much so that a rival train station was set up to compete with the one built by Schuster and co.

The accelerated developments in society during this period were mirrored in football, with the sport rapidly growing in popularity. An amateur Crystal Palace team played in the park as early as 1861, with ground staff from the site providing their players. This was not the club we know today: the modern Crystal Palace FC was formed separately in 1905, though they also played in the park for a time (hence the glass house featuring on their badge). They have since decamped to South Norwood and reached two FA Cup Finals, though their forerunners almost beat them to it by well over a century. The original club reached the semi-finals of the very first FA Cup in 1871-72, with a 3-0 replay defeat to Royal Engineers scuppering their chances.

That defeat saw the original Crystal Palace club miss out on a short trip to Kennington, where the inaugural Cup Final witnessed a 1-0 win for Wanderers over Royal Engineers at the Oval. Then as now this was very much a cricket ground, though the burgeoning sport of association football muscled in during the late 19th century. This was predominantly thanks to C. W. Alcock, who was secretary of both the Football Association and Surrey Cricket Club. A man of many talents – and, it would seem, considerable leisure time – Alcock also captained the victorious Wanderers side in 1872. The final decamped to Lillie Bridge Grounds in Brompton the following year, then returned to the Oval for the 1873-74 campaign. Save for the 1885-86 replay, which took the Cup all the way to Wrexham, it would remain in Kennington until 1891-92.

Kennington Oval, pictured in 1901, the original home of the FA Cup Final

Football’s growing popularity during this period can be seen in FA Cup Final attendances: the first is recorded at 2,000 spectators, while the last contested at the Oval two decades later drew 32,810.

The sport was undergoing a cultural revolution, too. While university old boys clubs had dominated the early finals, a new breed of team had emerged from the working classes of the Midlands, Lancashire and the North, making football a true game of the people. Blackburn Olympic, who had their roots in the local mills, broke the southern stranglehold in 1882-83, after which it would be 18 years before a London side reclaimed the Cup. And so the Final left the Oval for good in 1892-93, first heading to Fallowfield in Manchester and then Everton’s state-of-the-art Goodison Park the following year.

The Cup Final was travelling closer to the teams who contested it – and quite rightly, you might argue. But that didn’t sit well with the FA. In an attitude that feels familiar today, it was decided that the Cup Final should return to London. It was reasoned that fans from the provinces would enjoy a day out in the capital, with the fact that the FA and its senior members were based in London presumably mere coincidence.

READ MORE: How the 1980 FA Cup Final Changed Football

Back in Crystal Palace, the park had lost some of its original lustre but remained a grand if fading tourist draw. There had been changes, however. The elaborate fountains that once stretched to the skies had became too expensive to maintain and were removed and grassed over in 1894. With this work complete, the park’s south basin could be converted into something rather more practical – a spacious football ground.

And so it was that Crystal Palace was chosen as the new venue for the FA Cup Final from 1884-85 onwards. There was a degree of good sense to this. The park was still sufficiently impressive that it could provide a day out that went beyond football, with the enormous glass house providing a stunning backdrop that towered over the surrounding greenery. At the time, it was reasoned that families could arrive early in the day with a picnic and – this being 1895 – the men would head off to watch the game while the ladies took a leisurely stroll about the grounds. The rigid gender roles might now sound dated, but the idea itself was largely sound at the time.

That said, Crystal Palace is not the easiest part of London to reach today, so in 1895 it would have been a considerable challenge for those travelling from other parts of the country – and at this stage, those were the only teams contesting the Cup Final.

Nevertheless, the decision had been made and on 20 April 1895 the inaugural FA Cup Final to be held at Crystal Palace Park saw a pair of teams and their supporters trek in from the Midlands. To enjoy a day out in London, of course.

The finalists were Aston Villa – then English football’s powerhouse team – and local rivals West Bromwich Albion. The game was played on “a beautiful spring day”, which ensured a reported crowd of 42,500 in the park. Many were still not within sight of the pitch when, after 30 seconds, Villa’s Bob Chatt lashed home the only goal of the match. It came to be known as the ‘Crystal Palace thunderbolt’ and remained the fastest FA Cup Final goal until Louis Saha’s 25th-second strike for Everton in 2009.

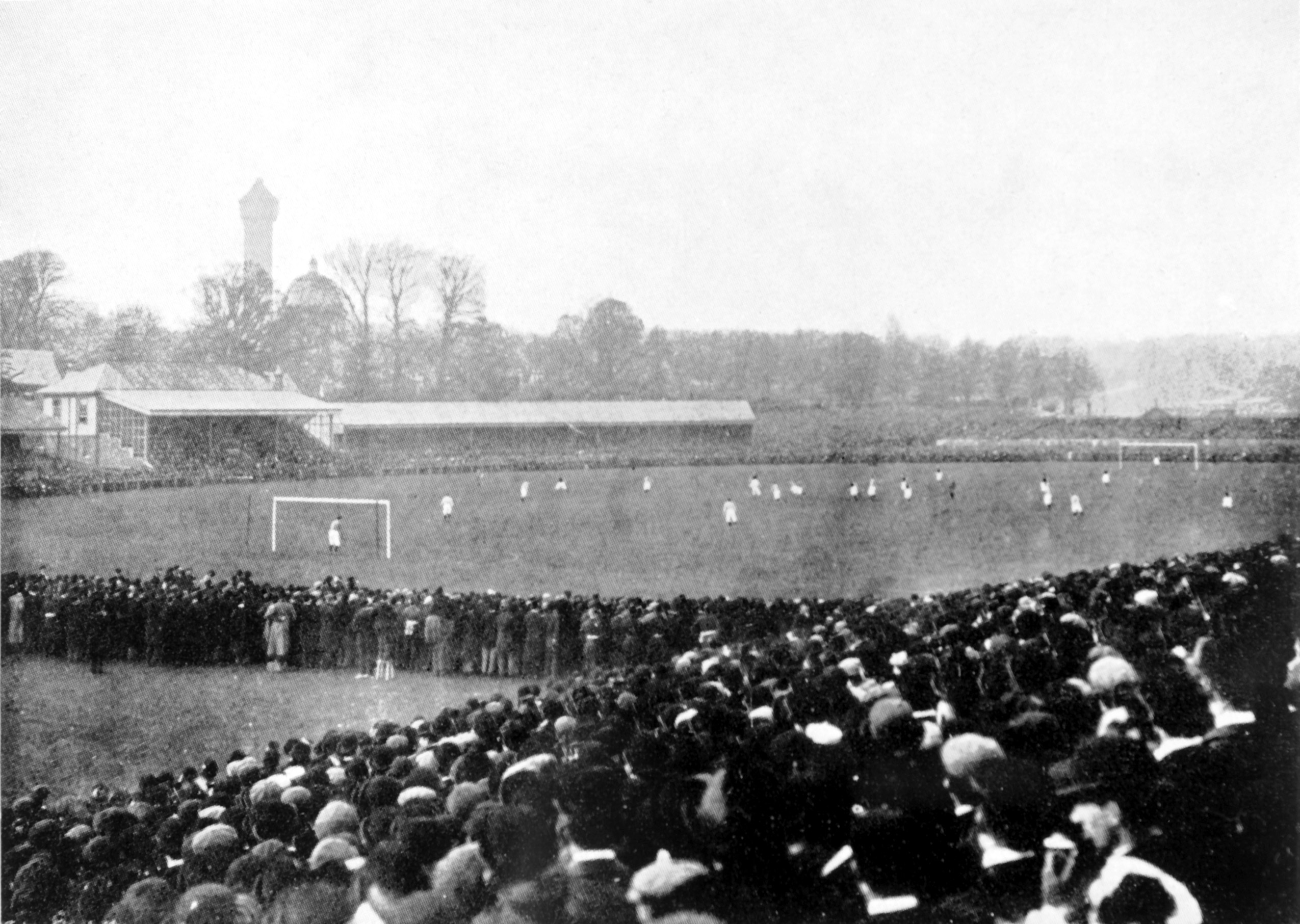

The 1905 FA Cup Final

Crystal Palace’s FA Cup experiment was a success. The crowd outstripped anything seen at the Oval and met the crucial FA criteria of being in London (though at the time this was technically Kent).

What’s more, attendances would continue to improve year on year. When Sheffield Wednesday beat Wolverhampton Wanderers 2-1 in the 1885-86 Cup Final, almost 49,000 spectators were present. The following year, when Villa won the trophy back, it was verging on 66,000. The Midlands club secured the double that day – quite literally, as league fixtures played elsewhere confirmed their domestic triumph. They are thus the only team to date to secure both parts of the double in a single day.

There were good crowds again for 1898-99, when Sheffield United beat Derby County 4-1 in front of almost 74,000; and 1899-1900 when Bury put four past Southampton without reply, watched by 69,000.

READ MORE: A Brief History of Footballers Living the Life of Crime

But those paled in comparison to the 1900-01 FA Cup Final, when an estimated 114,815 supporters piled into Crystal Palace Park to watch Tottenham Hotspur play Sheffield United.

Despite not yet being members of the Football League, Spurs became the first London club to reach the Cup Final since Clapham Rovers lifted the trophy in 1879-80. The vast crowd saw a classic. United were 1-0 up on 10 minutes, but Spurs levelled on 23 minutes through Sandy Brown. The North London side were in front six minutes after the break thanks to a second strike by Brown, only for the Blades to level immediately through Walter Bennett – though there was much debate as to whether this actually crossed the line.

With no more goals scored the game went to a replay, which in a curious fixture decision was played at Burnden Park in Bolton. A disappointing 20,000 were in attendance as Spurs became the only non-league side to win the FA Cup, beating Sheffield United 3-1. The Blades were not to be denied the following year, however, beating Southampton in another replay – this time back at Crystal Palace.

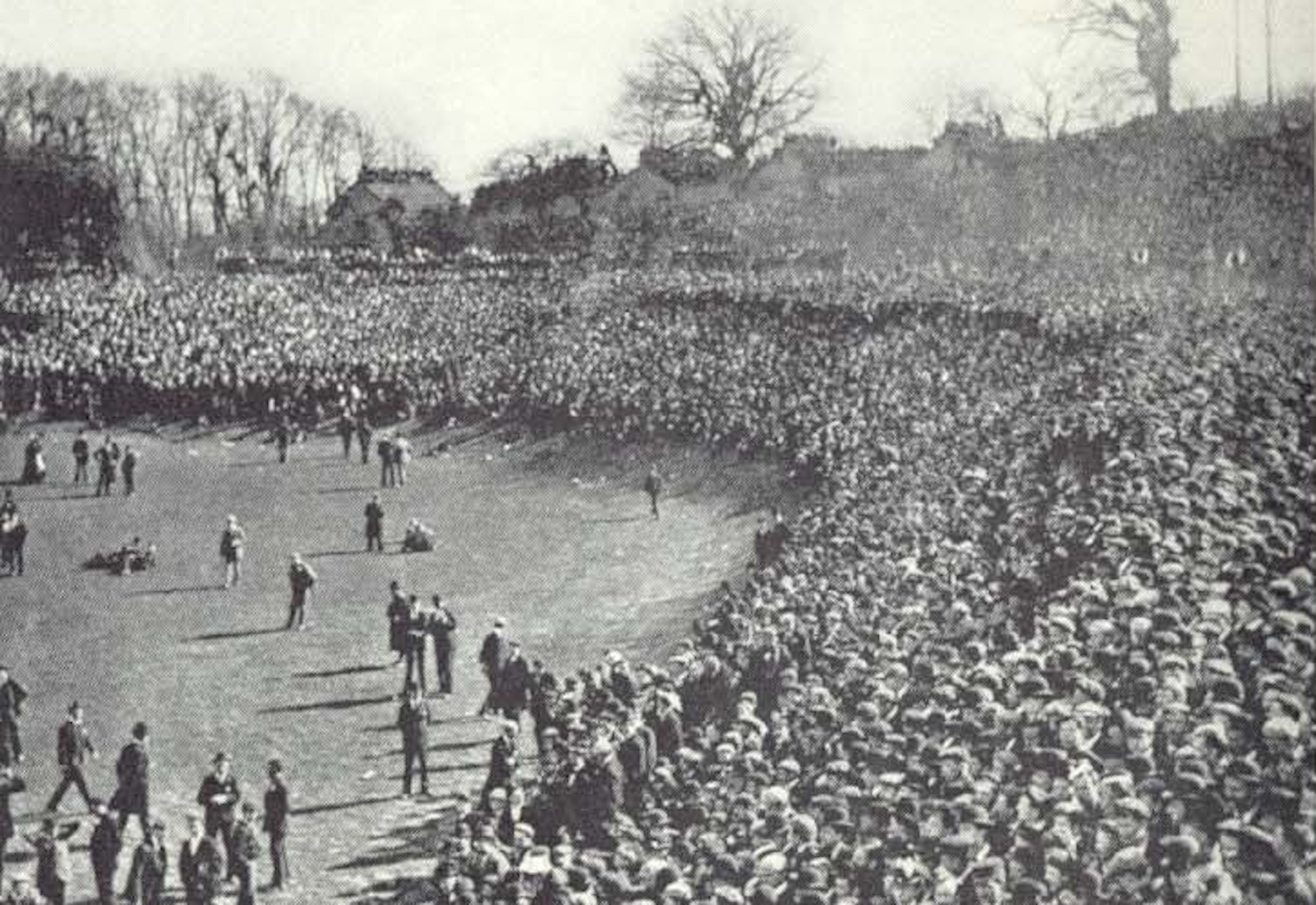

What might today be described as “absolute scenes” – 110,000 fans at the 1901 Cup Final

The venue saw another record set the next year, one that is yet to be broken. In 1902-03 Bury trounced Derby County 6-0, the biggest win in Cup Final history. 1903-04 was an all-Lancashire final contested by Manchester City and Bolton Wanderers, and while the FA’s notion of fans travelling to London sounded fanciful, it sometimes proved correct. A reported 30,000 descended upon London for the game, with many said to have slept on the platforms at Euston and St. Pancras stations the night before the match. Prime Minister Arthur Balfour and cricketing colossus W.G. Grace were also present to see City pick up their first major honour with a 1-0 victory.

The Cup continued at Crystal Palace Park for the next decade and crowds remained healthy throughout. It was partly because of this that, in September 1905, the modern day Crystal Palace FC was formed. The company who owned the venue realised that football’s significance to the area could be tapped into on a more regular basis, and despite opposition from the FA a new club was created to play at the stadium. They adopted the colours of Aston Villa, who a few months earlier had won their third FA Cup in the park. It was a suitable source of inspiration, albeit one they would eventually ditch in favour of mimicking Barcelona’s strip.

By the early years of the 20th century the venue was established as the home of the FA Cup. In 1905-06 Everton won their first major honour by beating Newcastle United by a goal to nil. The Toffees were defeated the following year, going down 2-1 to Sheffield Wednesday, while Wolves completed the double in 1907-08 by inflicting Newcastle United’s third FA Cup Final defeat in four years. Crystal Palace Park did not seem to favour the Magpies.

In 1909 Manchester United won the first of their record 12 FA Cups, beating Bristol City 1-0. The 1910, ’11 and ’12 Cup Finals all went to replays that decided the competition outside London: Newcastle finally won it in 1910, with Barnsley and Bradford City following them, earning both clubs’ only major honour to date.

United – in wonderful white and red chevron shirts – taking on Bristol City in 1909

In 1913, with interest in football continuing to swell, a new attendance record was set when 120,000 people watched the mighty Villa beat Sunderland 1-0 (only the 126,047 who saw the 1922-23 Final at Wembley tops it in the competition’s 145-year history). It also earned Villa their fourth triumph at Crystal Palace Park, making it a wonder that the area hasn’t become a site of holy pilgrimage for Villa fans.

The following Cup Final would be the last played at Crystal Palace Park, and it too was noteworthy. Firstly, both teams were playing in the big match for the first time, with Burnley beating Liverpool by a goal to nil. It remains the Clarets only major honour, though better was to come for Liverpool, who took an estimated 20,000 supporters to South London that day. They formed part of a 73,000 crowd that also included King George V, who became the first reigning monarch to attend the FA Cup Final.

But while attendances were good and the venue was deemed suitable for royalty, the Cup would not return to Crystal Palace Park. The 1914 Final was played on the eve of World War I and, when the conflict broke out, the park was taken over by the admiralty and used as a munitions depot.

PA Images

This also forced Crystal Palace FC out of the area. After a short nomadic spell they settled at Selhurst Park in 1924, roughly two miles from the old ground. Almost a century on they still call it home.

Though now largely forgotten as an FA Cup venue, Crystal Palace Park hosted a total of 20 finals. Only Wembley has staged more, albeit by a vast margin.

And it was a success when it came to attracting fans from outside the city. The passenger rail industry and travel companies like Thomas Cook ran special offers to transport fans to London for the game and laid on activities while they were there, ensuring healthy crowds for every Cup Final.

READ MORE: How Does the Football in TV’s Ripper Street Shape Up?

What it did not provide was a quality spectator experience. The largely flat basin on which the ground was located made views difficult, unless you were fortunate (that is, rich) enough to afford a seat in the pavilion. While 120,000 were present for the 1913 Final, quite how much they saw is another matter. Many took to climbing the park’s trees for a better view.

But perhaps this would have changed had the Cup Final remained in Crystal Palace. Development work would have become inevitable were it not for the war, which could have seen this quiet part of South London become as synonymous with the game as Wembley ultimately did. And perhaps it could have saved the Crystal Palace itself. The park hit trouble after the war and the great glass house burnt to the ground in 1936. A vast scar marking where it once stood is all that remains of one of the most significant buildings of the Victorian era.

The charred remains of the Crystal Palace, taken shortly after the fire that destroyed it. The flames could be seen 50 miles away in Brighton.

Ultimately, Crystal Palace should be remembered as a fitting home for the Cup Final during the game’s development from popular event into nationwide obsession. The presence of a building as imposing as the Crystal Palace lent the venue real gravitas. Perhaps it was not the best located, nor an ideal spectator spot, but the FA Cup’s sojourn in South London was emblematic of the era.