Morinth is dead.

Infected with a curse and known as an Ardat-Yakshi, she was never really alive. Any sexual intimacy she instigated would kill her partner. Morinth’s alien kindred offered her a life of celibacy and seclusion. She chose to run instead, fucking who she wanted, and setting the unjust world aflame. Her mother, Samara, lives. She hunts Morinth, and once she is dead, Samara will return to her other daughters. For her family, Morinth represents shame, the dark, the things we should not become. If Morinth’s sisters chose to run, they too would be dead, like Morinth is.

Videos by VICE

Samara and her daughters are asari, a single gendered race of blue, feminine humanoids from Mass Effect. The asari “still require a partner to reproduce. This second parent, however, may be of any species and any gender.” Conceptually, the asari offer a freedom from traditional ideas of gender and sexuality. The asari crewmember and potential romantic partner Liara is the source of countless lesbian and bisexual fanfic. The romance between her and protagonist Shepard is arguably one of the first examples of mainstream queer representation in video games. The appeal of an ambiguously matriarchal society, where everyone is pansexual by default, is not hard to understand. Morinth casts a shadow over this notion. She cuts to the heart of what makes the asari both resonant and troubling.

To dig into this, a fuller examination of asari is essential. Although they are canonically monogendered, and Mass Effect: Andromeda briefly gestures at a variety of potential Asari gender identities, asari function as galaxy-wide replacements for women. Until Mass Effect 3, women of other alien races—with the exception of the bodysuited, humanoid quarians—are only mentioned, never seen. Even when they do appear, in a major questline concerning the Krogan genophage and in the DLC Omega, they are hidden or cloaked. It is, understandably, difficult to create a wide variety of models for a large RPG. However, the decision to model a male default is a creative one more than it is a practical one, and it has wide reaching thematic implications for the series, and for the asari in particular.

Asari go through three different stages of life: maiden, matron, and matriarch. To quote from the series’ codex, an in-universe encyclopedia, “In the Maiden stage, they wander restlessly, seeking new knowledge and experience. When the Matron stage begins, they ‘meld’ with interesting partners to produce their offspring. This ends when they reach the Matriarch stage, where they assume the roles of leaders and councilors.” In essence, the asari move from feminine cliché to feminine cliché, from wild child to caring mother to wise woman. The game emphasizes that “each stage of life is marked by strong biological tendencies.” Though some might choose different lives, eventually motherhood and service is what each asari is destined for.

Outside of a few called out exceptions, most of the asari Shepard meets are in the maiden stage. Asari on the planet Illium, for example, frequently mention being mercs or strippers in their young lives. The games’ passive imagination about Asari often reflects this binary. While you do interact with Asari merchants, politicians, and scientists (Liara most noticeably) most encounters with asari fall into one of those two categories. From the asari commandos that make up some of the game’s mercenary groups to the dancers that populate its nightclubs, if an asari is not a major character or a merchant, they are a warrior or dancing set dressing.

There are moments where Mass Effect does push against itself. For example, both of the asari crewmates don’t fit neatly into the asari’s designated roles. Liara is a maiden, but rejects clubs and parties for archaelogical digsites. Samara is well into the matriarch stage of her life, but is instead a warrior monk or knight errant. Liara’s “father” Aethyta is, well, a butch matriarch. She is gruff and graceless, running a bar rather than working as a politician.

This wiggle room gives the asari resonance and makes them, at least, a complex example of sexy alien tropes. This is, perhaps, where the disconnect between how the asari are in the game and how many queer people online see them lies. There’s a lot of empty space in Mass Effect, especially the first game. Most of the game’s hard exposition is out of the way of the main path. It is thus an evocative universe. Reading the Asari’s codex entry is like cracking open the Dungeon and Dragons Player’s Handbook. Every race, from elf to dwarf, is riddled with racist assumptions. The fact that there is an intelligence stat belays this. By nature, though, the game offers space and opportunity for something new. It is easy to imagine a warlord Asari matriarch or a brash, childless matron poet. The Asari also have a long lifespan. If an asari goes through every stage as expected, they have hundreds of years of what we might call freedom. Afterwards, they may become mothers, but they still have real authority and power, something often not offered to their real world counterparts. Even in the ways it reinforces gender offers opportunities for subversion.

When I played Mass Effect as a teen, I saw myself in Liara. She’s a hundred years old at the start of the game, relatively young for an asari, but is sexually inexperienced. She has spent her whole life buried in books. Now, I see this as a nagging example of Mass Effect’s heteronormativity. Liara is a virgin, who is also definitely old enough for the player, presumably male, to sleep with. The subtext unveils, at best, a troubling and grossly straight sexual fantasy. However, I identified with Liara at the time, not Shepard. Religious, repressed, and nerdy, I felt that I was a million years old and distant from my peers. Before I “had” a body, Liara showed me one that, in retrospect, felt like my own. The asari’s ambiguous alien womanhood helped me explain something about myself to myself.

However, the problems with the asari root themselves in Mass Effect’s fundamental worldbuilding assumptions and the game’s passive imagination. Of course these assumptions can be erased in fan fiction, but it is much more difficult to cut them out of the games themselves. Samara and Aethyta might seem to reach beyond the roles of the asari, but live in their shadow. Aethyta still dishes out age-old asari wisdom, but behind a bar with a scotch in hand, rather than at a university or congress. Samara is not a warrior monk by choice, but rather a failed matron. She birthed monsters, the aforementioned Ardat Yatshi, instead of children. Her calling is an atonement against the sin of her children’s existence.

Those monsters, the Ardat-Yakshi, are the hard edge with which every queer reading of Mass Effect must reckon. They are, to put it crassly, psychic sex vampires. They kill their partners in intercourse, overwhelming their minds and devouring them psychically. Thus, they can conceive no children. After the act, they become smarter, faster, stronger, and crave another such encounter. Ardat-Yatshi are the result of one of the asari’s only taboos: intraspecies asari relationships. These romances are discouraged because, as Liara puts it, “Asari daughters inherit racial traits from the father species. If both parents are asari, nothing has been gained. Or so conventional wisdom would hold.” In short, though the Asari are monogender, their culture recreates the importance of a kind of sexual difference and of childbearing.

On one hand, Mass Effect makes the asari’s idea of queerness definitionally different from Earth’s. Though a woman’s relationship with an asari would be seen as queer by humans, it would not be by asari. This gives yet more of the aforementioned wiggle room. It is pleasant, for obvious reasons, to imagine a future where a wide spectrum of relationships are accepted, without oppression. On the other hand, Asari culture centers on reproduction and motherhood. It marginalizes asari for not centering their lives on their future children or on the advancement of the asari as a race. Intraspecies asari relationships are, in some ways, the queer deviation against which the “normal” asari family is judged. The Ardat-Yakshi are an extension of that marginalization. While asari couples are allowed equal treatment, at least on paper, the Ardat-Yakshi, the source of the taboo against intra-species relationships, are not. They articulate the gay panic of years past and present, in which “promiscous” queer people are imagined to be inherently violent and diseased, unworthy of help.

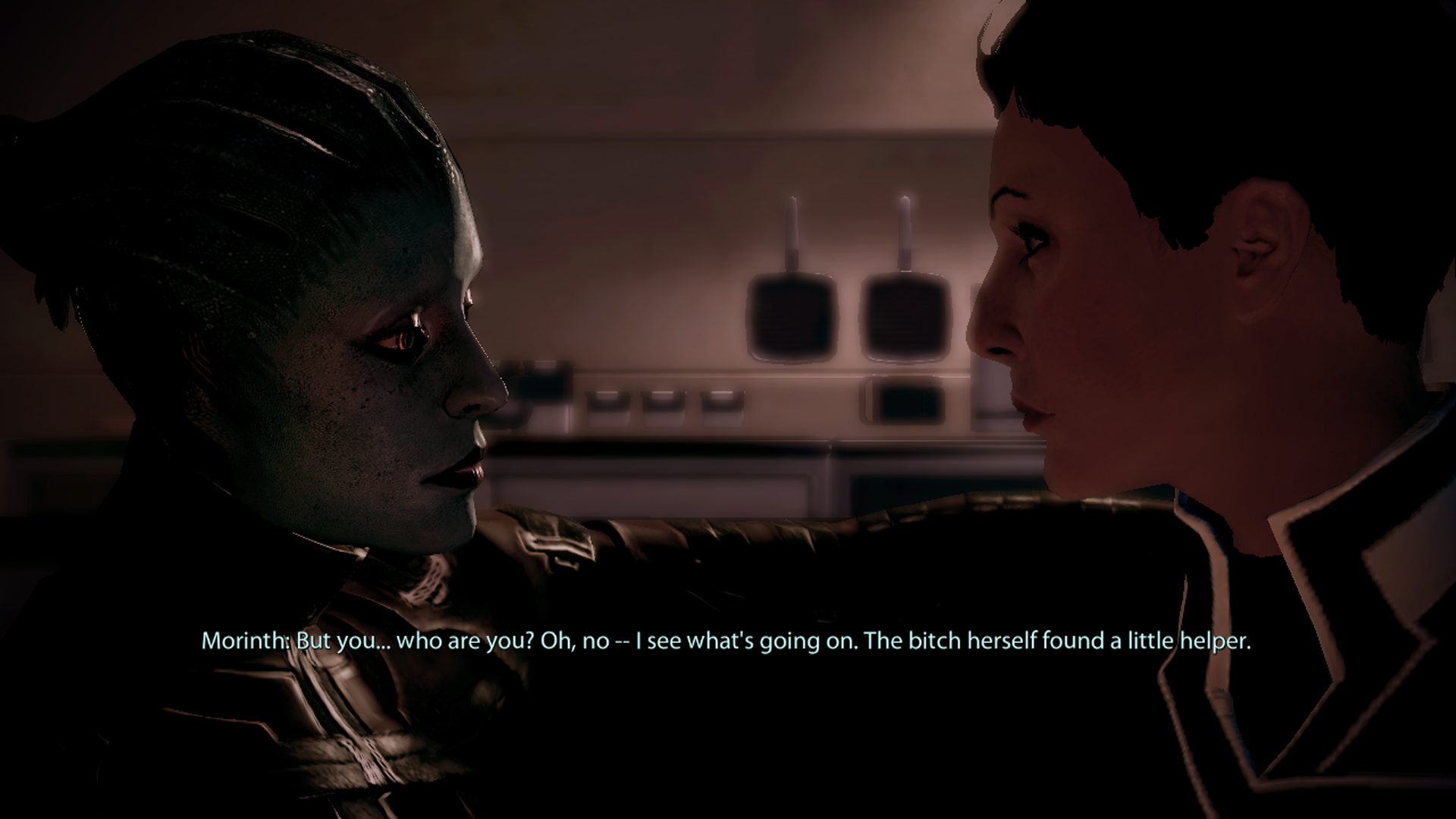

The galaxy’s only known Ardat-Yatshi are Samara’s own daughters. Two chose to live in celibacy and seclusion. The third, Morinth, ran. Samara asks Shepard to help her pursue Morinth in an extensive sidequest. Shepard, whether a man or woman, must enter a nightclub and lure Morinth into a trap set by Samara. Throughout the quest, Morinth tells Shepard how much she craves danger, the thrill of the hunt, and uses racialized language to describe her feelings: “I love clubs—people, movement, heat. I can still hear the bass, like the drums of a great hunt, out for your blood.” The clear implication is that the casual sexual encounter Morinth promises and the violence she hides are “primitive,” left behind by modern culture. It is impossible to separate this implication from racism. Her condition, her own urge to kill, comes from a genetic defect, echoing eugenics and facism. She is literally degenerate; a person who cannot live. Samara calls her “a disease to be purged.”

Inextricably connected to Morinth’s racialization is her defect’s uncomfortable echo of AIDS. She is a person with whom sex is inherently violent and dangerous. Just as queer people were abandoned by systems of medical care and government assistance, the asari refuse Morinth any kind of structure or freedom. Her further existence only serves to put other people in danger. The only way for her to live is in seclusion or as a sexual deviant or predator, a false binary that is thrust on many queer youth growing up. However, Morinth has no alternative. There is no freedom for her, no option that does not make her a monster. Though the sidequest’s final choice is killing Morinth or Samara, Morinth faces death either way. She appears only briefly in Mass Effect 3, as a powerful, but otherwise unnoteworthy enemy, transformed by the franchise’s villains. If Samara does live, she appears in Mass Effect 3 in a mission to rescue her remaining daughters. Her absence is thus keenly felt. If Morinth lives, she sends Shepard an email and then dies. A queer person that could not assimilate, the only option for Morinth is destruction.

I wept while playing this mission. I wept in anger. As AIDS first ravaged queer communities across the United States, it was not treated as tragedy or even a medical emergency, but as the rightful smiting of the degenerate. Queer people who dared to have sex, who would not assimilate into straight world, deserved death. Morinth is a parallel to the many people who died. In place of the uncaring state is Samara’s fist. Among the principle asari, Liara is the one who the game celebrates. She is Morinth’s opposite in many ways. Also a “pureblood,” she is not cursed. She waits a long time to have sex with the right person. Liara’s relationship with Shepard is the only kind of queerness Mass Effect will recognize, one that can be immediately exchanged for a normative straight relationship.

The asari could have been different. Examples abound in works long predating Mass Effect. Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness explores a mono-gendered alien culture with tact and nuance. In one scene a human, Genly Ai, and a monogendered Gethian, Estraven, discuss the differences between their cultures. “Ai brooded, and after some time he said, ‘You’re isolated, and undivided. Perhaps you are as obsessed with wholeness as we are with dualism.’”

Estraven replies, “‘We are dualists too. Duality is an essential, isn’t it? So long as there is myself and the other.’” In other words, for the Gethians, otherness comes not from inherent sexual or racial difference, but in the inherent distance between two aware beings. In the same conversation Estraven asks, “Tell me, how does the other sex of your race differ from yours?” To Estraven, the idea of a gendered otherness is completely foreign; it must be explained. Both of these moments bring out something Mass Effect never quite explores, at least with the asari: the encounter with something speculative that can recolor or even transform preconceived notions.

In theory, the asari represent a break from traditional, human modes of gender. In practice, they recreate specific queer discourses of human history, offering either assimilation or death to its queer analogs. In a deeper sense, there is no tension between how asari see themselves and how the galaxy sees them. They happily slot into whatever understanding of femininity existed before them. The Gethians, though, disturb Ai. They trouble his notions of what it means to be a man, of what otherness means, and thereby question our own. I don’t want to hold The Left Hand of Darkness up as the perfect counterexample. Some of the book’s central thesis come off as obvious or quaint now, when gender fluidity has reached mainstream discourse. However, it is still a celebrated work of science fiction because it asks the right questions. Furthermore, it was published before video games were anything close to a household item. Mass Effect should have learned from it.

Still, many have found resonance, whether troubled or euphoric, in Mass Effect’s queer lives. It is difficult to underestimate the power of seeing yourself, even in a twisted, broken, blue mirror. I did not write this to disparage such resonances, but rather to prove that we deserve, and can do, better. Mass Effect’s flickers of resonance give us more than enough to smash its mirror, and to use its shards to relight our image. While in the confines of fiction, Morinth may die alone, wild children may grow to become compliant mothers and matriarchs, and voiceless dancers may squalor in shadows. Real people are not so confined. The universe that awaits us is so much more expansive than Mass Effect could ever imagine. I hope, despite the flickers of truth in these games, we can prove how little we ever needed them.