I walk among the mind flayers unseen. I get the odd thrill of walking somewhere you’re not supposed to. Were I there as a player, this is one of the most hostile areas I could be at. But I’m there as a DM, wearing the silly default avatar for dungeon masters in Neverwinter Nights, and as such the monsters placidly ignore me as they go about their inscrutable business.

Deep in that corner of the Underdark, I come across a prostrate skeleton; some kind of trapped ghost, his presumed spirit a purplish skull floating in the silver surface of a mirror. Examining the body brings up a story: “Izlude the Sorcerer was actually a player character in the early days of Arelith. This is an example of how players can influence the world; if you’re lucky, you could end up in his position!” I’m told that if I zoom in close, I can hear him crying.

Videos by VICE

Throughout the nineties, western role-playing games were trying to replicate the tabletop RPG experience; Bioware had the D&D license and tried to build direct digital translations of that game, but everyone was chasing this particular dragon in some form or another.

While games like Baldur’s Gate and Fallout were successful and critically acclaimed, they only delivered pre-scripted (if branching) narratives. However surprising the plot twist, however complex the world-building, they never really replicated the actual experience of sitting down at a table with a DM and three other players to build a story together. That feeling would stay on tabletops, and eventually studios would move on to focus on other strengths of the digital RPG with titles like Mass Effect and The Witcher.

Neverwinter Nights built the tabletop experience into a digital game in a way that really worked. It did this with a “DM client” that let players join as dungeon masters in multiplayer sessions, able to take control of NPCs and change the game world on the fly to adapt to an emerging story with the players. Neverwinter Nights was not the only game doing this; but it combined that feature with powerful level-creation tools that allowed for fully custom scenarios, and more accessible online play than was possible even a few years before. But it was the digital tabletop built for the dawn of the online gaming era, carrying the weight (and the familiar ruleset) of the most popular tabletop RPG of all time.

On the eve of Beamdog’s Enhanced Edition re-release of the game, I went back to look at what community remains playing that game, and at its persistent worlds—multiplayer servers that run continuously and accommodate multiple playgroups, miniature MMOs in themselves. That landed me on Arelith, NWN’s longest-lived and largest persistent world. Having run since 2003, it exemplifies Bioware’s hopes for its toolset. Daniel “Irongron” Morris, the server’s current owner, agreed to show me around.

Arelith is both a treasure and a road not taken. After Neverwinter Nights, the genre forked: Bioware, CD Projekt Red, and others focused on building carefully authored single-player experiences, while Blizzard and others (well, mainly Blizzard) built the great Western MMO: Vast worlds with complex mechanics, interlocking systems, and huge numbers of concurrent players.

Persistent worlds like Arelith are neither of these. They’re story-focused, but with a story that emerges from interactions between players rather than pre-scripted quests. All one has to do to create a persistent world is run the server software on any computer continuously; maybe you rent a server on a rack somewhere, or nowadays use a virtual private server rented from Amazon or Google or a smaller provider. Or, as was the case with Arelith for a while, your PW can just be a dedicated computer that lives in your basement. Independent from any one company’s services, persistent worlds exist outside of the “platforms” of today’s internet—a bit like “multi-user dungeons” that are the common ancestor to both multiplayer RPGs and MMOs. They belong to the world of independent sites of yesteryear—and, I hope, of tomorrow.

A whirlwind tour of Arelith, led by Morris and his fellow dungeon masters, takes up the better part of two hours, and I’m sure I haven’t seen even a tenth of what’s in there. All the way through, I pick his brain about level design in this game (building areas to make player traffic work out is crucial), about his player base (he tries to cater to a mix of all four Bartle types), about the history and geography of the world he tends.

Morris got involved with Neverwinter Nights around its 2002 launch, after playing isometric RPGs all through the nineties. NWN was, at the time, full of promise, and he credits this replication of the pen-and-paper player-DM relationship. “All those other games had the mechanics and setting of an RPG, but weren’t able to offer the full experience.”

The Neverwinter Nights series was the last hurrah for single-player (and non-MMO multiplayer) licensed D&D games. Obsidian, rather than Bioware, released Neverwinter Nights 2 in 2009, with less success than its predecessor. After that, D&D became the domain of action-RPG licensed games with little to recommend them, and the little-loved MMO Neverwinter. Between Neverwinter Nights and Neverwinter Nights 2, the style of game that NWN stood for—isometric, mouse-driven, D&D-influenced, single-player or small-scale multiplayer—would become a niche, and not the default, as games like Mass Effect and World of Warcraft broke out of that mould.

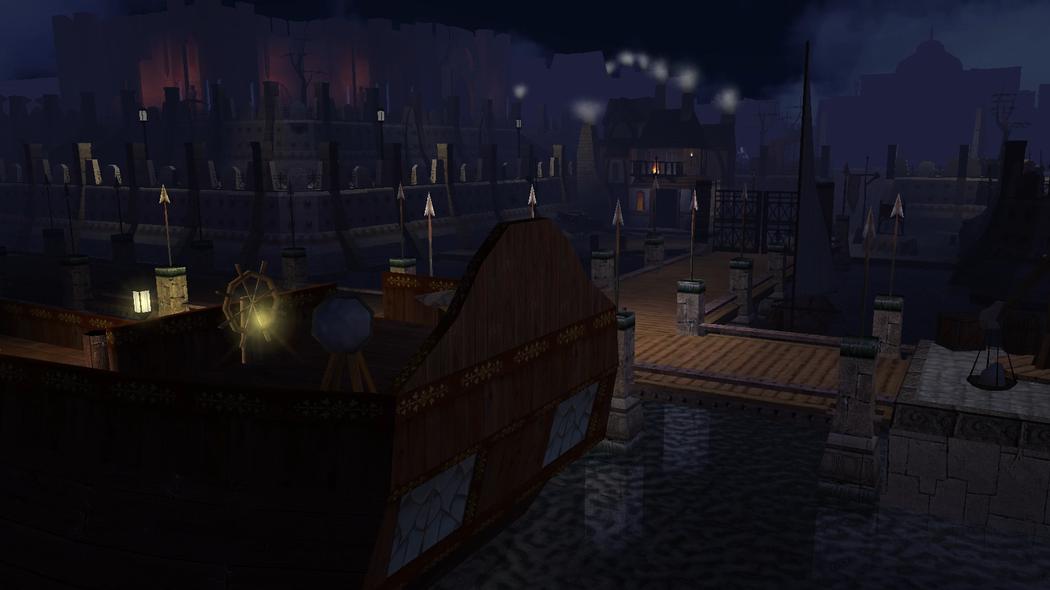

If Mass Effect is a film, and World of Warcraft is a theme park, then Neverwinter Nights is more like theater. Its world is a stage of blocky tiles laid out on a grid, each one the size of a tiny room; the smallest space the game can support. It’s a world straight out of a cardboard dungeon-building set, and careful placement of props is essential to break up the blockiness and unreality of those designs. Arelith in particular is built with a maniacal dedication to prop placement. Using only models and textures from the original game, it still looks much more vivid than the campaigns that shipped with the game. Part of this is a hobbyist’s attention to detail; part of this is getting to use many more polygons than BioWare could afford to include in a game meant for 2002 computers.

“With enough dressing, and careful lighting, you’ll see the original NWN tilesets can really shine,” Irongron tells me. Dead branches lie on stream beds; rocks just out from the edge of a waterfall; a country road curves around a boulder. It’s a curiously organic world, for a place that I know is underpinned by a grid.

At one point during my tour, I’m taken to a map composed of a few ships at sea under a red sky. This is not really connected to the rest of the game world; instead, it’s a location that’s in place just waiting for a DM to use it, just in case a naval battle is called for at some point.

There’s a coherent, self-sufficient game world; but there’s also all those loose tools for players and DMs to pick up and play with, enriching their role-play with props and mechanics. I always knew what the NWN level design tools were capable of, and that there was such a thing as a “DM client,” but it’s something else to see all that technology in action. It’s like looking at a D&D table mid-game, miniatures and gridded terrain maps strewn about. Except you can move your mini off the edge and find yourself on a whole other table.

Later on, I leap at the chance to talk to some of the server’s regulars. A small crowd forms on a sandy beach somewhere, and I gamely start pitching them questions. How long have they been playing? What are some of their favorite stories? (“That time I got a cat out of a tree.” “You mean that time I got a cat out of a tree.”). I get too many answers to quote, but it’s clear that this DM-player symbiosis is crucial to what makes this place special to them. Nobody’s here for the charming low-poly graphics or for the specifics of D&D’s rules; they’re here for a type of space newer games don’t provide for them.

The word immersion gets used a bunch in this discussion. And here, it feels meaningful and precise. Arelith’s players sink themselves into a world that they’ve constructed for themselves, one where their actions feel consequential because it’s a shared story; because others have to contend with what they do. They stay in-character throughout their play, inhabiting the ongoing lives of identities they’ve built along with others on this server. I feel all the more like an interloper for breaking that magic circle to ask them questions.

A year of real-world time is roughly equivalent to ten years of notional in-game time; at present, Arelith has some 120 in-universe years of recorded history, all of it made up of player-driven storylines spiralling out and becoming major historical events. Entire cities have been razed, their maps changed from bustling towns to broken ruins to reflect story events. In Arelith’s central city, a museum commemorates all kinds of in-world histories, art, and even fiction.

Izlude the Sorcerer, weeping at the bottom of a dungeon forever, is the endpoint of this idea. Arelith is a small passion project where players can make creative, long-lasting changes to the world; where they can build history. Changes to World of Warcraft’s Azeroth are born in a meeting room somewhere in Irvine. Changes to Arelith are born out of what players do in the game itself, from players directly placing props and objects into the world, to months-long storylines culminating in entire villages being permanently razed.

Arelith started as just a way for a small group of friends to play together, but it eventually escalated into a large, long-lived community. “Originally, Arelith was started just because we wanted a place to play that was fun, but also fair,” Arelith’s founder Jeremy “Jjjerm” Martin told me. “I’d played on another server for a while, and saw it torn apart by partiality and DM favoritism.”

Arelith is now much bigger than that original friend group, but a sense of conviviality persists. Seeing the players and DMs bounce off each other as they answer my questions reminds me of experiences I’ve had with MUDs; there’s an ongoing story here that everyone is very much invested in. But it doesn’t feel in-jokey in an impenetrable way; I think that if I wanted to make a character and join in, I’d find my bearings quickly.

Arelith directly rewards role-playing, leading to stories outside the traditional D&D milieu—one player (going by “Vespidae”) tells me she’s been playing as a farmer, complete with “a pitchfork and a dog and everything.” Irongron picks up on this: “There’s a lot to be said for playing an ‘ordinary person’ because on Arelith you still get into extraordinary situations with them.” Achievement takes a backseat to inhabiting this world; that notion of immersion showing up again.

Arelith’s success stems largely from behind-the-scenes work. Getting buy-in from the growing community to make changes; successfully transitioning power to new owners. Arelith has passed through three different owners; the second one, James “Mithreas” Donnithorne-Tait, emphasized the significance of this: “Most servers that have died, have died because their original leaders stepped back, and the successor didn’t have the same faith from the player base; and that created friction that tore the whole server apart.”

Article continues below

All this to attract and retain players, a virtuous cycle where activity begets more activity. It’s drilled into me when I talk to the players: Players are the story; players are the content, players are the consequences. The job of DMs is to pick up on what’s going on and build on it, to help the improv along, and every so often to just make the players’ lives difficult. One player, using his in-game name “Stylo,” tells me of walking into a building wearing the same color cloak as another PC and becoming the fall guy for their crimes. A fortuitous event like that might spiral into a server-spanning storyline as different player groups intersect and collide.

Strong community management is a central pillar of what keeps Arelith going. In-game communications between players are done through text chat, not voice, which makes it possible to keep thorough logs. Hand-picked DMs keep tabs on potential problem players through those logs. Developers who work on scripting and building the game world aren’t allowed to log on as DMs, only as normal players, enforcing a separation between those who build the game world, and those in charge of running it day to day.

It hasn’t always been smooth sailing; I get the sense that these standards have evolved over time, through a lot of trial and error. But Arelith’s team of admins have been doing this for longer than almost anyone else. Few MUDs and MMOs from that era survive today. And in the commercial MMO space, subject to normal employee churn, you won’t easily find the long continuity of management that exists on Arelith. Over the years, they’ve had to find consistent ways of dealing with everything from in-game disagreements between players, to forum accounts being hijacked by neo-nazis, to setting PG-13 expectations for new players coming from NWN’s very active “erotic role-play” community.

All this history is now standing at the edge of the biggest change it has ever experienced. Arelith has grown on top of the same foundations through server changes, playerbase turnover, and many generations of PC hardware. The imminent release of Neverwinter Nights: Enhanced Edition (due to be released “when it’s done,” but already in open beta testing) carries with it a lot of promise and worry for players.

Beamdog has put the existing community at the center of their efforts to revitalize Neverwinter Nights, going as far as hiring directly from the community and asking Morris to produce a custom persistent world based on Arelith for a livestream back in December. Backwards compatibility, and no apparent intention to introduce some kind of “persistent worlds as a service” scheme, means that existing worlds will be able to switch as soon as the game is out. The independence, and thus potential, of persistent worlds will remain.

Arelith has survived thanks to careful tending; its ability to retain admins, and have continuity between different server owners over the years, has let it continue to grow where many other persistent worlds have fallen silent. But the release of the Enhanced Edition anticipates a firehose of attention directed at Arelith and the existing Neverwinter Nights community. But the players I encountered reacted to this mostly with excitement. More people to play with, more mods, more modules to try, all brought on by a more accessible game and that new cycle of attention directed at it.

And Neverwinter Nights deserves that attention. The promise of what it was doing was to allow players to create their own third places , welcoming social spaces where external social hierarchies don’t hold, relationships aren’t mediated by money, and new friendships can happen. This has become increasingly uncommon in in online gaming; when was the last time a video game pushed you to make friends as opposed to bring your friends along?

Of course, the very tools that enable this (the pervasive text chat, the freeform player interactions) are themselves more vulnerable to abuse, more humanely fraught. That Arelith uses them for the purpose they are meant for is an achievement, the result of careful tending. And it is such a frightening thing to do, as a game developer, to ship a game with these kinds of tools; it runs so far counter to how we expect a major studio to behave today, to the frictionless and heavily mediated experiences that form the core of a Destiny 2 or an Overwatch.

In many ways, persistent worlds remain as a reminder of the internet that was (and could be again). They’re not accounts on a service someone else owns. You have to own, or rent, a server to operate them. Arelith lived for years in a basement, before being moved over to a cloud hosting platform. While Neverwinter Nights has a “master server,” that server acts as a catalogue, not as host to everyone else’s persistent worlds. They remain as institutions of a truly decentralized internet . Arelith’s admins truly own all of the user data on their server, from the world itself to the characters that inhabit it.

This real ownership allows for a space to exist that doesn’t have to serve anyone’s commercial aims. Arelith’s admins pay the hosting and bandwidth costs of the server, with help from a small patreon. That Neverwinter Nights, up until recently, was not really a going revenue stream for Bioware, Atari, or Hasbro couldn’t impede its continued existence. Unlike many MMO guilds and other “social gaming” features through the years, Arelith could never have its plug abruptly pulled by a studio or a publisher. Persistent worlds were conceived as a way of putting more value in the game box, not as a way of extracting value from players after release.

In an industry where the overwhelming sense is now often that things are only allowed to exist if they make money for someone, persistent worlds have carved out room for play that exists outside those boundaries. And that play takes forms that can only exist because of those material conditions; because it doesn’t have to make money for someone.

I keep going back to Izlude the Sorcerer, moaning away in his corner of a dungeon. Arelith exists in a sort of goldilocks zone where it’s small enough that things like that can still happen – players can still, truly, fill in the blanks on the maps of the world. But at the same time, it’s big enough that the marks they leave feel momentous. Many adventuring parties have since come and gone in that dungeon, and heard Izlude’s sad tale; one player’s experience fed into the stories of dozens of others, and over time, the world becomes saturated with those kinds of details. It’s a tabletop with the deep scratches of dozens of other playgroups that have been there before.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Sony Interactive Entertainment -

Screenshot: Electronic Arts -

Screenshot: Warner Bros. Games -

Screenshot: THQ Nordic