People with dreams of grandeur move to New York in search of fame. Dilara Erbay came here to get away from it.

Dilara has lived many lives: a political scientist, a vagabond, a nightclub manager, an illegal restaurant owner, a globally renowned chef, a food artist. Now she just wants to remain anonymous.

Videos by VICE

She had already acquired all the fame she could stomach back in Istanbul, where she was famous for creating inventive and complex versions of simple Turkish recipes. Life at the top of the city’s restaurant scene became a soul-sucking endeavor, and eventually, she says, she just yearned for simplicity. That’s how the third iteration of her restaurant, Abracadabra, was born.

The tiny, four-table cafe is hidden in plain sight on Bedford Avenue, the busiest street in the beating heart of Williamsburg. But only five years ago, Abracadabra was housed in a four-story Ottoman-era mansion in the posh Arnavutköy neighborhood of Istanbul. Looking at the bare-bones, stoveless kitchen she works out of today, it’s hard to imagine she held the reins over a 10-person team who cooked in front of a glistening backdrop of the Bosphorous Sea.

A destination for Istanbul’s socialites, Abracadabra in Istanbul was the object of praise from local and international media, its chef credited as one of pioneers of New Turkish Cuisine, paving the way for a culinary revolution in Istanbul.

“We became big and fancy, and everybody wanted to show up there to be seen. I was not nurturing myself anymore,” Dilara says. “There, everybody knew me, and they wanted to see what I was going to do next. I don’t like to be known. I like to be underground. Here I can do anything—people are open to any creative ideas or craziness, they don’t judge you.”

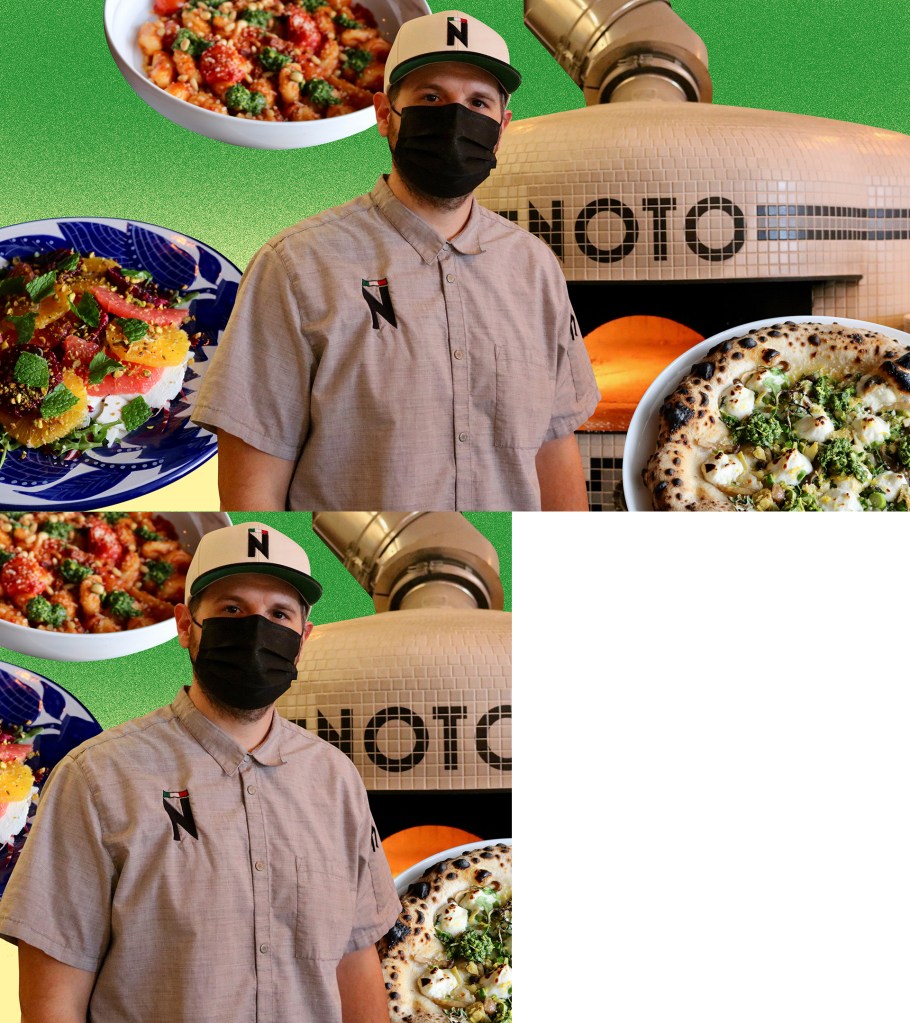

More than a chef, Dilara considers herself a food artist, and in Istanbul, she was a food artist whose only canvass was in her restaurant’s kitchen. In New York, she’s able to make magic outside the walls of Abracadabra.

When she arrived in New York, she stumbled upon a community of artists through Kitchensurfing, a now-defunct website that was kind of like Airbnb for people looking to hire in-home chefs for one-off dinners. Her first and only client ended up being William Etundi, one of New York’s most celebrated underground party producers, famous for throwing the Danger parties of the aughts and more recently the You Are So Lucky parties that have taken place at a 72-room mansion just outside the city.

“With 10 people, we were producing the best food in Turkey.”

It wasn’t long before Dilara was cooking for the VIPs at his parties, and eventually found herself the chef of some of the city’s wildest events—burlesque nights, elegant and mystical affairs, orgiastic evenings reminiscent of something out of Eyes Wide Shut. And Dilara provides the food, with presentation to match the atmospheres party producers create. In the past that has meant soup and chocolate served in ceramic molded lips, aphrodisiacs served by naked servers, and most recently, turning a woman into a living cake covered head to toe in whipped cream, fruit, and flowers at last weekend’s You Are So Lucky.

READ MORE: Inside the Last Pork Butcher Shop in Istanbul

It’s her night job as a food artist and her history in Istanbul that make her humble Williamsburg cafe even more surprising. Her current menu reads more like something you’d find at a yoga retreat or at a cafe in Portland: vegan and gluten-free ‘Inca warrior power cookies’ made with oats, coconut butter, coconut sugar, chia, flax and sunflower seed; ‘veganizer’ Turkish burritos; homemade ‘Love Hurts, Love Works’ raw chocolate, made with cayenne pepper and bee pollen.

The menu in Istanbul couldn’t have been more different. It included dishes wholly unique to the city, dishes that Turkish grandmothers would have found sacrilegious: “ çiğ köfte” made with salmon tartar and bulgur rather than with the raw meat typical at kebab houses around the country, and Armenian rice with mussels and currants rather than traditional rice pilaf. Years later, those recipes can still be found at some of the city’s top restaurants—like 360 Istanbul.

“With 10 people, we were producing the best food in Turkey,” she says.

Dilara never intended to be a chef. After graduating from college, she was a political scientist who became disillusioned about her ability to make any changes in a system “where there is no democracy.” So she packed up her stuff and headed to Colombia to learn to scuba dive. In order to pay for her divemaster license, she started cooking at the dive center’s restaurant, and it wasn’t long before word got around Taganga, then a sleepy fishing village—and now backpacker cesspool— about the town’s new international restaurant.

She returned home a year later, and after a brief stint managing the nightclub Godet, the precursor to Mini Müzikhol, she opened a restaurant of her own, albeit not legally. The tiny storefront had no name, no license, and no real kitchen—all the cooking was done on a camping stove.

“We took electricity from the mosque, water from the street, and everything was illegal,” Dilara says.

READ MORE: Istanbul’s Breakfast Heaven Is a Kurdish Feast

But it was here in this skeletal kitchen that the current Abracadabra really has it’s roots.

It wasn’t long until word got around about the “crazy” chef serving locals along with rich tourists—and, once, Dilara says, a Kuwaiti prince—who came to the Cukurcuma Beyoglu neighborhood looking for antiques. A friend soon asked her to run his restaurant, Dulcinea, but she had no idea how to run a real kitchen, so she flew to New York to staj at Tribeca Grill.

At Dulcinea, she met her husband, Ahmed, who helped her open the first iteration of Abracadabra after she spent a year touring around the small villages of Turkey to learn traditional recipes. She returned from her village tour armed with a new catalogue of ingredients and recipes, and combined them with the techniques she picked up at Tribeca Grill.

“I called the kitchen traditional and experimental,” Dilara says. “The international press became very interested because it was not on the scene—Turkish cuisine besides donor and kebab—so my little Abracadabra became a big Abracadabra.”

At the second, much larger iteration of Abracadabra, she served diners everything from sun-dried eggplant filled with spicy lamb and rice with Indian mint masala to a pen-thin burek inspired by Sufi cuisine, stuffed with pesto and pastrami, and served with sweet and spicy sauce.

“She was definitely a real breath of fresh air on the Istanbul dining scene,” says Istanbul Eats co-author and editor of Culinary Backstreets editor Yigal Schleifer. “Turkish cuisine is great, but there’s a real conservative streak that can run through the cooking, just because people always like things the way they’ve always been made and the way they should be made. She was one of first people to start having fun with it and making interesting tweaks and bringing in different ingredients.”

Abracadabra wasn’t just about what came out on the plate, but what was being done in the open kitchen: views of the dishes sizzling away, ships rolling past on the Bosphorus in the distance, and the wild spectacle that went on many nights. The entire staff would dance around, making music with the pots and pans, while belly dancers rolled around on the kitchen counter.

“Her rise coincided in many ways with the rise of Istanbul during very much of a golden age for her and for the city, so there was a lot of excitement, and Istanbul was in this very dynamic forward-looking period,” Schleifer says. “She was part of helping create that image in Istanbul, and she was also a beneficiary of what was going on, so she was able to grow quite quickly because of that period.”

But after awhile, the passion fizzled out, and according to Dilara, the customer-base cared more about the scene than the food. Plus, the rent became too damn high.

“My project over there really made me unhappy,” she says. “This mansion, even me, as the owner of the place, I could eat over there only once in a month if I had to pay… Good food doesn’t have to be that expensive.”

So her new approach became serving healthy, organic food. The menu at Abracadabra in Brooklyn is a lot more pared down both out of convenience and out of necessity. Like her no-name illegal restaurant in Istanbul, Abracadabra has no full kitchen. There’s no ventilation, so everything from the kofte to the chicken tikka to the various pastries are cooked in the oven. Only soup (made on a camping stove), salads, and smoothies are made outside the oven.

Considering her background in Istanbul, and her penchant for the fantastical, you might think that cooking in a kitchen without ventilation, with a price point that maxes out at $12.50 (for a main with coconut wild rice, green hummus, red cabbage pickles, kale salad and homemade hot sauce) might limit her creativity. But she sees it as a way to more fully express herself and an opportunity to serve good food anyone can afford.

“I can provide affordable food for everybody, and we are very ethical with everything and with all the oils we use: only coconut oil, olive oil and ghee.

“I say it’s good for everybody. So i’m gluten-free friendly, vegan friendly, meat friendly, chicken friendly. We welcome everybody. As Rumi says, ‘Come as you are.’”

Even if that means coming naked and covered and covered in frosting.